The Romanian Ministry of National Defense has requested the approval of the Parliament to begin the design and execution of the barracks on the air base Mihail Kogalniceanu, according to Radio Free Europe.

In May 2020, Romanian Defense Minister Nicolae Ciuca sent a letter to the legislature explaining, among other things, that Romania wants to be “a pole of stability on the EU’s and NATO eastern flank including militarily.” For this objective to become a reality, Minister Ciucă says that it is necessary to “rethink and resize the existing facilities in the area of Mihail Kogalniceanu aerodrome and bring them to an appropriate level of development”.

The Romanian military has long mulled expanding the air base used by the US troops. About 500 American soldiers are stationed at the Mihail Kogălniceanu air base, but Romania hopes that their number will increase and together with the Romanian soldiers it will reach 10,000.

Last year, the Pentagon postponed a $22 million investment project to this military base and redirected the money to other investments. However Romania started its own work on the base.

A tool of control

The Mihail Kogălniceanu airbase demonstrates how the geopolitics of the Black Sea region are connected with the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf.

The base, which occupies part of the territory of the Michael Kogelnichanu International Airport, is located about 30 km from the largest seaport of Romania, Constanta and 13 km from the Black Sea littoral. During the fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US Air Force used this Romanian base as a transit base.

According to the plans of the Ministry of Defense of Romania, after re-equipment and expansion, the base will be able to receive F-16 multi-functional fighters, which are in service with the Romanian Air Force, as well as F-35s.

The current size of the base was suitable for the support of the American operations in the Middle East. However, its expansion is now under consideration.

A large-scale modernization to the tune of billions of euros might be needed to transform the “airdrome ” into something more – a strategic air base that would allow the United States and NATO to control the Black Sea and the surrounding region.

Romanian ambitions

In recent years, Romania has demonstrated a desire to become a US stronghold on the Black Sea. The country, which has only 244 km coastline, has Naval Forces that consist mainly of outdated ships and only one major port on the Black Sea present itself as a stronghold of the US military machine in Eastern Europe.

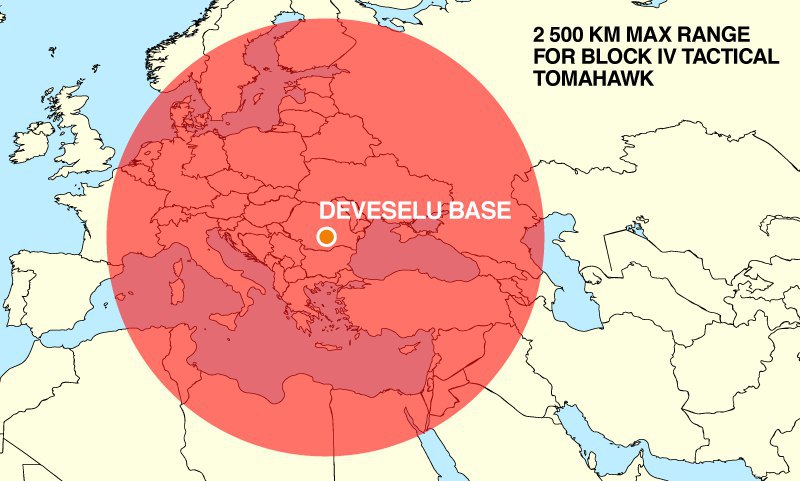

In Romania, în addition to the Mihail Kogălniceanu base, there is a major element of the US missile defense system, the US Navy Aegis Ashore missile defense system. In theory, it has both attack components and functions. From the Standard SM-3 (Mk 41 vertical launch system) missile launchers, strategic Tomahawk cruise missiles with a range of 2500 km can be launched.

In fact, the Americans demonstrated this capability in the Tomahawk last August, using the same Mk 41 to launch ground based missiles after the INF Treaty exit.

In its military modernization program, Romania showed interest in new American weapons includingPatriot missiles, but the programs for the acquisition of new coastal defense systems and ships are constantly postponed.

Obviously, despite its military weakness, Bucharest is seeking to demonstrate that Washington may use its territory for its own military plans. Back in February 2019, then-Prime Minister of Romania Viorica Dancila proposed to develop a strategy that would consider the situation in the Black Sea as an integral part of the security of the entire Euro-Atlantic region.

At the same time, in favor of increasing the US military presence on its territory, Romania is promoting an arms race. Other countries – primarily Russia – will have to respond by strengthening its Black Sea grouping (especially in Crimea).

It was on the strengthening of the US missile defense in Deveselu that Russia put on combat duty the first hypersonic “Kinzhal” missiles in the south of the country. At the same time, the Black Sea Fleet received six new submarines of project 636.3 “Warszawianka”, with Syria “3M-54 Kalibr r” cruise missiles on board. Four divisions of S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems were deployed in Crimea.

Replacing Turkey?

Formally, US military facilities in Romania are aimed at countering possible missile attacks by Iran, as well as at deterring Russia. However, the latter task is only a part of the broader goal – to ensure US control over the Black Sea region as a whole. It is indicative that Romania became particularly active in the political life of the Black Sea region after the suppression of the military coup in Turkey in 2016. Bucharest seeks to promote itself as a pillar of the US in the region and at the same time a kind of substitute for Turkey.

It is worth noting that US neoconservative pundit Michael Rubin declares that bases in Romania, together with the possibility of being based in Jordan, may become a substitute for the Incirlik air base in the US states.

The cooling of relations between the US and Turkey, which controls the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, has significantly reduced the ability of Americans to project power in the region. Against this backdrop, the role of Ankara in the Black Sea direction became ambiguous in Washington.

On May 27, 2020 the Washington DC-based CEPA think-tank published a report authored by former US European Army Commander General Ben Hodges “‘One Flank, One Threat, One Presence: A Strategy for NATO’s Eastern Flank”, where Hodges proposed “Reinforce Romania” “As the center of gravity of NATO’s regional deterrence”, Create NATO A2/AD “Bubbles”, “Strengthen the defense of the Western Black Sea with unmanned maritime systems and ground-based systems in Romania including anti ship missiles, drones, and rotary wing attack aviation”.

The document also proposes: “Improving Romania’s ISTAR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition, and Reconnaissance) capabilities” and “Invest in Romania’s Cyber Capabilities”.

As Admiral Cem Gürdeniz has already noted, these plans, together with the initiative to establish NATO Black Sea Standing Maritime Patrolling, “pose serious danger to destabilize the Montreux Treaty of Turkish straits and to disrupt the regional balance”.

It is indicative that last year, the RAND Corporation, affiliated with the CIA and the Pentagon, the Bucharest Office of the German Marshall Fund (GMF) of the United States and the Aspen Institute Romania organized a workshop on “Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Strategy: Regional Perspectives”. The workshop was sponsored by the United States European Command (EUCOM).

As a result, a report was issued which stated the need to strengthen the US presence in Romania and even the “westernization” of the country.

“There is also a need for more credible and sustainable military deterrent posture. Romania and Bulgaria cannot confront Russia by themselves, and Turkey’s commitment to alliance in a future crisis with Russia has become uncertain”, says the report, prepared with Pentagon money.

It also asserts that Russia “finds a willing partner in Turkey” in reshaping “regional security arrangements”.

In January 2020, RAND released another report – “Turkey’s Nationalist Course: Implications for the US-Turkish Strategic Partnership and the US Army”, also funded by the Pentagon. (https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2589.html), which recognizes that “Both Russia and Turkey have long resisted attempts by outside powers to penetrate the region” and their interests partially coincide in the Black Sea region.

Turkish-Russian “military cooperation in the Black Sea and Syria” is also mentioned as a matter of concern for NATO.

At the same time, RAND analysts recognize that even if Turkey remains a “difficult ally” with the US it would be “reluctant to support NATO presence in Southeast Europe and the Black Sea”. And in the most radical scenario – Turkey becoming a Eurasian power and seceding from NATO – “it would find new modus vivendi” with Russia “in the Black Sea region and the Caucasus”.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington declares that “Turkey’s value as an asset for NATO in the Black Sea is being questioned” and the US may “even replace Ankara with Bucharest as its privileged partner in the Black Sea region”.

“The enthusiastic US contribution to the renovation of military infrastructure and troop deployments in Romania could be an early signal of a more structural evolution”.

Common front: Black Sea-Mediterranean

Thus, Turkey is considered by American and Romanian analysts as a power whose interests are directly opposed to the expansion of the US and NATO presence in the Black Sea.

The US seeks to strengthen its presence in Romania in opposition to the interests of the two major Black Sea powers – Turkey and Russia. If Russia’s deterrence is openly declared by Washington, then Turkey’s deterrence in the Black Sea has not yet been spoken about openly – yet it holds the keys to the sea.

In recent years of bold naval modernization, Turkey has strengthened its geopolitical position in the Aegean, the Black Sea and in the Eastern Mediterranean, but, as a country with the longest Black Sea coastline and the control over straits, it has special interests on the Black Sea.

The militarization of the region by the US and its new “privileged partner” Romania leads to higher tensions in the region and increased Russian activity. All of this will force Turkey to shift much of its forces and attention from the Eastern Mediterranean toward maintaining the country’s security in the Black Sea.

On the other hand, as the proposed expansion Mihail Kogalniceanu air base itself shows, security in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea and even the Persian Gulf are interconnected. This is a united front. And on this front, a single holistic strategy must be applied.

This is what the Americans do – counteracting Turkey and Russia at the same time in the Mediterranean while building a new architecture of dominance in the Black Sea.

Romania, and with it, US partners such as Bulgaria and Georgia, are turning their peoples into hostages to Washington’s imperialist Black Sea policy. At the same time, Bucharest is doing this solely out of geopolitical ambitions. This ambition can only be contrasted with increased cooperation between Russia and Turkey in the region, the search for new partners (for example, Abkhazia) and promotion of Turkish interests as the country most interested in peace and lack of tension in the Black Sea by diplomatic means.

Leave a Reply