By Tunç Akkoç

The “China policy” to be followed by the new US President Joe Biden is a major issue about which many people are most curious. Statements made one after the other in recent weeks were serious clues about the direction Biden will take on this issue. Firstly, US Secretary of State Blinken issued clear statements about China. Considering China as the biggest rival of the US in the military, economic, and geopolitical arena, Blinken said Trump was right to take a tough approach towards China.

On February 10, 2020, during his visit to the Pentagon, US President Joe Biden announced a unit called “China Task Force” established within the ministry to focus only on China-related matters:

“The Working Group will align its recommendations with inter-agency partners so that the Department of Defense continues to support a total and consistent government approach toward China. […] If we do not act, they will overtake us. We have to speed up,” Biden said, after a two-hour phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The new team

New appointments to important tasks also drew attention in this context. These appointments, which provided insight about the US administration’s attitude towards China, received similar comments in the public opinion –Joe Biden was forming a team suitable for his fight against China. Apparently, US foreign policy will be based on competition with the People’s Republic of China.

Joe Biden picked Katherine Tai as US Trade Representative. Katherine Tai’s ties with China are interesting. Tai’s mother and father were born in China, she grew up in Taiwan, then settled in America. Tai, who speaks Chinese and is teaching English at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou after getting her bachelor’s degree from Yale University, is very familiar with China. The new US Trade Minister Gina Raimondo also came to the fore with his recent statement. Answering the questions of Republican Senators at Congress, Raimondo was noncommittal when it came to the question of Huawei, the Chinese tech giant that was blacklisted by the Trump administration. On January 29, Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor to the United States, said they need to improve their relations with the allies in order to put pressure on Beijing. Sullivan also stated he would put great emphasis on repairing relations with his European and Asian partners who share their frustration toward China:

“While the US accounts for a quarter of the global economy, this proportion doubles when combined with that of its allies,” Sullivan added.

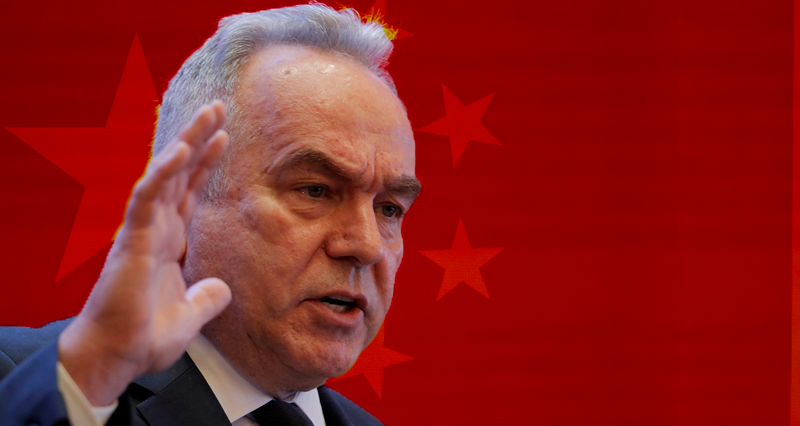

China policy’s mentor

US President Joe Biden has appointed Kurt M. Campbell as his “Asia coordinator”. Campbell is an Asia expert who was enrolled to the National Security Council. Formerly serving as Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs in the Obama administration, Campbell is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relation (CFR) and the person behind the “China policy” that the US administration will follow.

In an article recently published in Foreign Affairs, Campbell outlined the strategy he believes that the US should follow against China. The article, titled “How America can shore up Asian order? A Strategy for Restoring Balance and Legitimacy”, discusses how China can be “balanced” in the Pacific geography and how to restrain its power. (1)

Today’s Asia is like Europe in the 19th Century

Drawing an analogy between the dynamics of today’s Indo-Pacific geography and the social and economic conditions of Europe in the 19th century, Campbell lists the following phenomena that overlap in the two periods: a rising state, great powers in competition, various channels of conflict, growing nationalism, conflict between liberalism and authoritarianism, and fragile regional institutions.

What the States needs to do today is to modernize and strengthen the elements of an existing system, but to create order out of chaos like the European leaders of the 19th century.

Two specific challenges, however, threaten the Asian order’s balance and legitimacy, according to Campbell: “The first is China’s economic and military rise. The second challenge is the original architect and longtime sponsor of the present system—the United States. President Donald Trump himself strained virtually every element of the region’s operating system. Trump was also generally absent from regional multilateral processes and economic negotiations, ceding ground for China to rewrite rules central to the order’s content and legitimacy. This combination of Chinese assertiveness and U.S. ambivalence has left the region in flux. If the next U.S. administration wants to preserve the regional operating system that has generated peace and unprecedented prosperity, it needs to begin by addressing each of these trends in turn.”

The US should restore the balance

Defining the United States as the former protector of the Indo-Pacific geography and the ‘father’ of the 40-year-old peaceful order, Campbell claims that this balance has been disrupted by China recently.

The course of action, which he later refers to as “restoring balance” and can be seen as an innocent suggestion at first glance, means increasing the US intervention in the region and limiting China’s influence:

“China’s growing material power has indeed destabilized the region’s delicate balance and emboldened Beijing’s territorial adventurism. Left unchecked, Chinese behavior could end the region’s long peace.”

On the other hand, various military means and new methods, he writes, should be used:

“Beijing spends more on its military than all its Indo-Pacific neighbors combined. In response to these threats, the United States needs to make a conscious effort to deter Chinese adventurism.”

At this point, he is not refraining from criticizing the practices of the Trump administration: “Washington can start by moving away from its singular focus on primacy and the expensive and vulnerable platforms such as aircraft carriers designed to maintain it. Instead, the United States should prioritize deterring China through the same relatively inexpensive and asymmetric capabilities Beijing has long employed. This means investing in long-range conventional cruise and ballistic missiles, unmanned carrier-based strike aircraft and underwater vehicles, guided-missile submarines, and high-speed strike weapons. These developments would complicate Chinese calculations and force Beijing to reevaluate whether risky provocations would succeed.”

The recommendations of Campbell, also known as the ‘China director’ of US President Biden, are not limited on military measures. In addition to making the US’ armed presence in the region more effective, arming countries in the region is also emphasized.

“The United States needs to help states in the Indo-Pacific develop their own asymmetric capabilities to deter Chinese behavior. Although Washington should maintain its forward presence, it also needs to work with other states to disperse U.S. forces across Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. […] The United States should encourage new military and intelligence partnerships between regional states, while still deepening those relationships in which the United States plays a major role…”

Bringing China under control through other Asian countries

One of the main ideas of Campbell’s article is that “China’s territorial adventurism and coercive economic policies” undermine the ‘legitimate order’ in Asia. The same charges are made against the former Trump administration. If those trends continue, “the regional states may drift into China’s shadow.’’ Moreover, “the dynamic region might split into spheres of influence: outside powers shut out, disputes resolved through force, economic coercion the norm, U.S. alliances weakened.”

Since international legitimacy relies heavily on economic relations, Campbell also proposes alternative economic methods for the region. “… it [the USA] can reassure wary regional states that moving supply chains out of China will often mean shifting them to other local economies, creating new growth opportunities. Moreover, as China provides infrastructure financing through the Belt and Road Initiative, the United States should develop ways to provide alternative financing and technical assistance.”

So, what should China’s role be in an “Asian order” where the US is the playmaker? That’s one of the most complicated issues, according to Campbell:

“Although Indo-Pacific states seek U.S. help to preserve their autonomy in the face of China’s rise, they realize it is neither practical nor profitable to exclude Beijing from Asia’s vibrant future. Nor do the region’s states want to be forced to “choose” between the two superpowers.” “A better solution would be for the United States and its partners to persuade China that there are benefits to a competitive but peaceful region organized around a few essential requirements: a place for Beijing in the regional order; Chinese membership in the order’s primary institutions; a predictable commercial environment if the country plays by the rules…”

As a result, Campbell envisages a regional order whose rules are set by the US and whose international legitimacy is also determined by the US:

“Washington will have to work with others to strengthen the system, provide Beijing with incentives to engage productively, and then collectively design penalties if China decides to take steps that threaten the larger order.”

The most challenging task in recent history

“… the United States should pursue bespoke or ad hoc bodies focused on individual problems, such as the D-10 proposed by the United Kingdom (the G-7 democracies plus Australia, India, and South Korea).” “Other coalitions, though, might focus on military deterrence by expanding the so-called Quad…” “The purpose of these different coalitions—and this broader strategy—is to create balance in some cases, bolster consensus on important facets of the regional order in others, and send a message that there are risks to China’s present course. This task will be among the most challenging in the recent history of American statecraft.”

Campbell’s determination seems realistic. Indeed, the United States has not encountered a bigger challenge than this in the last half century. This situation is better understood considering the level China has reached today. But Campbell’s proposed roadmap for the United States does not seem practicable and realistic. More clearly, it is impossible to mention a United States that is capable of limiting the Belt and Road Initiative, weakening China’s cooperation with countries in the region, and organizing a new armament in the Pacific. In this sense, Campbell suggests a strategy that goes beyond the power and possibilities of the US.

The China challenge can help America avert decline

In another article he wrote in December 2020, shortly before taking office, Campbell put forward some interesting theses. (2)

Stating that there have been theories and phases regarding the “decline of the US” since the beginning of the 20th century, Campbell states that elements of theories of collapse are being experienced today and that this started with the financial crisis in 2008:

“For the United States, decline is less a condition than a choice. Economic inequality, the urban-rural divide, social media algorithms, and unrestricted campaign contributions have intensified domestic division.”

According to Campbell, there is only one way the US can survive this decline, and that is to follow an effective and comprehensive China policy:

“The path away from decline, meanwhile, may run through a rare area susceptible to bipartisan consensus: the need for the United States to rise to the China challenge. … The arrival of an external competitor has often pushed the United States to become its best self; handled judiciously, it can once again.” How this climate will be created and how the spirit of unity will be recreated within the country is described as follows: “The more assertive and repressive China becomes, the more likely the public and Congress are to unify around concerns about Beijing’s long-term intentions and the impact of its state-backed mercantilism on American workers and businesses.”

“Not with a free market”

In the article titled “The China challenge can help America avert decline,” Campbell shows the fight against China as a way out for the United States:

“With a constructive China policy that strengthens the United States at home and makes it more competitive abroad, American leaders can begin to reverse the impression of U.S. decline.”

However, it is argued that the US must undergo some structural changes in order to cope with China. With the rules of the free market economy, they cannot achieve results with the initiative of market forces alone, Campbell writes:

“The United States will also have to rethink the relationship between the state and the market. Many figures in both parties now acknowledge that market forces alone cannot halt inequality, sustain growth, secure the country, or ensure competitiveness against China’s state champions.”

As a result, Campbell argues that the American state can only compete with China thanks to the effective involvement of the public in the field of economy, and lists some steps to be taken in this regard:

“This realization could provide support for investments in science and technology and even justify elements of a progressive agenda—efforts to support workers, break up monopolies, and conduct industrial policy in critical sectors such as semiconductors.”

1. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-01-12/how-america-can-shore-asian-order

2. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-12-03/china-challenge-can-help-america-avert-decline

Leave a Reply