The Ottoman Empire was the last great Islamic Empire which looked after Muslims rights as per the stipulations of the Caliphate since 1517 to 1924. There are a number of archival documents to evidence this historical reality in the Ottoman archives. In the age of global expeditions by the Europeans from the beginning in the fifteenth century, the native people of different nationalities were oppressed by colonial powers all over the world, but particularly in Africa. The indigenous people created a protection mechanism in their own land against colonial powers. The most important element here was undoubtedly the response of the Ottoman State towards the request of the poor people for protection. The Sultans of the Ottoman State tried to do their level best for these people. Many religious issues were successfully managed under the control of the Ottoman State for the welfare of the Muslims by the Sultans.[i]

Ottoman traces in Southern Africa

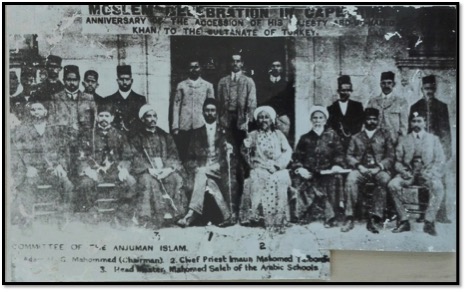

The Sultans of the Empire were respected by the Muslim Society during their reign and gained popularity among Muslims in India, Java, and Ache as well as in South Africa.[ii] The Turkish State had supporters from all over the world because of its religious connections with the Muslim communities. According to the archival documents, the Ottoman culture was promulgated in the years following the arrival of Abu Bakr Effendi in the Cape Colony. In 1864, a local newspaper, South African Advertiser noted that:

The Turkish Consul- General and the Malays.

Thursday several of the Mohammedan Priests of Cape Town had an interview with the Hon. Mr De Roubaix, Consul –General for Turkey. The interview took place at the special request of the priests, who were anxious to have an account of the honourable gentleman’s visit to Constantinople. I need hardly tell you that the matter to which I allude stands connected with the mission of Abu Bakr Effendi, who is now in Cape Town.[iii]

In 1867, a South African Advertiser noted another important event on its pages under the heading ‘Malay Celebration of the Sultan’s Birthday’. According to the news, “The last Saturday was quite a busy day with the Malay Population of Cape Town, on the occasion of the anniversary of the birthday of the Sultan of Turkey, which was celebrated in various Malay mosques for the first time in the chief mosque in Chappini Street, tastefully decorated with evergreen plants and flags. The Malays had set a day aside in order to honour the sultan, by complimenting him on his birthday for his benevolent consideration for the co-religionists of the Musselman in this colony.”

Consequently, the respect for the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire transcended the geographical boundaries of the Ottoman Territory, and the mental boundaries of the State. The implementation the Caliphate’s duty was an important mission for the Sultans. The administrators of the Ottoman state in Istanbul had not neglected these missions for the sake of Allah. This conservatism allowed the Sultans to gain honour and esteem from the global community of Muslims. It was one of the results of holy targets of the Ottoman Caliphate.[iv] Despite the considerable geographical distance between Ottoman State and South Africa, the Ottoman State gave due consideration to the issues faced by Muslims at the tip of the Good Hope.[v] An important theologian was sent by the Sultan to South Africa to educate the Muslims there and guide them on their Islamic beliefs and practices. The Ottoman scholar Abu Bakr Effendi arrived in the Cape Colony in 1863 and spent his entire life with Muslim Community to teach them Islamic principles[vi] When he died in 1880, his valuable legacy and influence were visible among the Cape Muslims. The contributions of Abu Bakr Effendi were developed by the Muslim Society in South Africa. His significant works can still be seen in the Muslim Society in Cape Town.[vii]

Ottoman Fez in South Africa

There is a remarkable story about this event to prove my argument in the historical context. In 1914, the British Empire brought many slaves from all over the world to fight for them in the Great War. The soldiers were fighting in the Gallipoli War against to the Ottoman Amy to occupy Istanbul. After the war, the British soldiers returned to their own country. When some of them returned to South Africa which was a British Colony at that time, the Anzack soldiers saw the Turkish Fez on the heads of the South African Muslims. The slave soldiers were worried because of the supposed Ottoman presence at the Cape[viii]. They had seen same fez in the Ottoman territory during the campaign while fighting against Ottoman Soldiers. At that time, South African Malay Muslims used to wear the Ottoman traditional cap on account of the influence of Abu Bakr Effendi. From this, the British Soldiers assumed that Ottoman Amy had occupied the Cape Colony when they were at war in the Ottoman territory in Asia Minor. South Africa had certainly not been occupied by the Ottomans, but it is possible to say that people’s hearts were occupied by deep admiration for the Ottoman Caliphate.[ix]

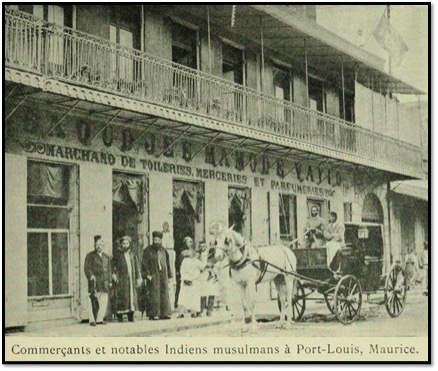

In another country, The Muslim community in Mauritius also raised funds for the children of Turkish martyrs in the Turco-Italy War in Libya. They even sent a donation to the Ottoman soldiers fighting in the Balkan War. The Ottoman Caliphate honoured them with the Majidia medals for their thoughtfulness all the way to Istanbul from Mauritius.

Ikhwat-ul Islam

Port Louis

21 April 1914

Very Dear Brother

Asalamoalaikum wa ramatoullah wa barakalah,

Further to the medal by the order of Medjidi-h that you received from the Imperial Majesty the Sultan of Turkey and Khalifat-ul-Musalman in recognition of your dedication to the Islamic cause during the Italo and Balkan-Turkish wars, I have the honour to convey to you the Society’s congratulations, voted by the General Assembly in its meeting this Sunday the 19th. We are very proud of this honorific distinction that you have received, and we hope that you will work even harder for the Islamic cause, particularly for the creation of Yatimkhana, which the colony needs even more, and you will further glorify your name and will deserve the blessings of the widows, orphans and disabled.

I remain your brother in Islam, 1914.

M.A. A. Gonmany[x]

In addition, during the First World War, Mauritian Muslims continued to support the Ottoman Empire. Mauritanian Muslims also prayed for the Turkish National Army, which was led by the founder of modern Turkey, Ghazi Mustafa Kemal Pasha.

In the national archives of South Africa, there are many interesting documents related to this topic which take us back in history to better understand the events as historians. One of them is about the Turkish flag issue which took a place in the British – Turkish political correspondences during that time.[xi]

Archival documents report particular correspondence about Turkish flags hoisted atop Mosques in Cape Town. While the Turkish flag hoisting may illustrate the sympathy for the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire who were their benefactors, in time, it became a matter of concern for the local administrators. A particular Ottoman archival document illustrates the Turkish Flags issue in the following manner.

Governor –General’s Office

Cape Town

26th February, 1917

Dear Fowle

With reference to your letter no, 1705. 3 of the 21st February. We have no information as to the attitude adopted by the Imperial Government towards the use of the Turkish Flag on Mohammedan Mosques. There are Mosques in many other towns in South Africa; it would presumably be easy to find out whether it is their practice to fly a Turkish flag for religious purposes. It is a general Muhammadan practice- there must be plenty of Europeans in South Africa who could speak with authority on this point – it worth hardly seem worthwhile interfering with it; but if it is not a general practice there seems no reason why the Muhammedans of Dundee should be allowed to continue doing something which is offensive to other people and is not a customary necessary part of their religion.

Yours sincerely

P. Horsfall

These archival documents show us how the Ottoman Empire was concerned by the issues of the Muslims all over the World. In this regard, we can examine the flag subject in terms of the solidarity of Muslim against the Colonial powers. The flag of the Ottoman State not only symbolised the sovereignty of the justice of the Caliphates, but it was also an indicator of the welfare mentality that guided the sultans’ administrative approach during their sultanates.

The mental boundaries of the Ottoman Empire

As clearly seen in the documents, the Ottoman State attempted to help the poor people in the World whenever they were informed regarding problems they encountered. This genuine humanity provided Islamic unity among the Muslims under the control of the Ottoman State. It may not be too easy to control peoples composed of many different religions, sects, races, and cultures, living in its dominions but during the Ottoman Period, it occurs often and successfully because of the justice constitution of the Ottoman State. This is an obvious reality, living in peace and security has always been an arduous target throughout human history. The Ottoman Empire was capable of ruling justly in this diverse and colourful community. Therefore, people having many different beliefs, freely carried on with their own religions, languages, and cultures. This important fact has created solidarity amongst all Muslims. While some Muslim leaders wanted to visit the Sultan, some of them wanted to send a letter to him to show their gratitude towards him.[xii]

Due to this solidarity, some of the Muslim religious leaders claimed publicly to have a prayer in the mosque for the Sultan of the Ottoman State. According to them, the Ottoman State was a kind of protector and also benefactor for them. The Turkish Flags were hoisted mosques in many countries when they were praying for the Sultan. To the Muslims, the flag of the Ottomans symbolized the sovereignty of the power of Islam. However, the colonial rulers in the Cape Colony were worried about this question because of the probability that the Ottoman influence could hamper their dominance in the Colony. Therefore, the Cape Colony flags in the mosques became a political issue. The governor of the colony informed the Minister of foreign affairs of the British Empire at the time. An archive document provides us with important information which explains the flags issue with the title of ‘office of the governor-general of South Africa. For this reason, the influence of the Ottoman Empire in the lives of Muslim people in South Africa cannot be overlooked. The Ottoman fez or the Ottoman flags in the mosques in South Africa are items of depicting the appreciation of the South African Muslim community for the Ottoman State. This is indeed a mentionable historical reality in our past. Due to the just administration system of the Ottoman Empire, the Ottoman dignity will remain in the pages of history.

Notes

[i] Response to Western colonialism: Ottoman legacy in Africa, https://unitedworldint.com/8532-response-to-western-colonialism-ottoman-legacy-in-africa/, accessed 05, 09, 2021.

[ii] Ottoman Empire’s Relations with Southern Africa- Ahmet Kavas Doç. Dr., Istanbul Ü. Ilâhiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, aüifd Xlviii (2007), sayi II, s. 11-20

[iii] South African Advertiser, 13 February 1867, p.3 Malay Celebration of the Sultan’s Birthday

[iv] Opposition to the Ottoman Caliphate in the Early Years of Abdul Hamid II: 1877-1882 Ş. Tufan Buzpinar, Source: Die Welt des Islam, New Series, Vol. 36, Issue 1 (March 1996), pp. 59-89. Also see, A vindication of the Ottoman Sultan’s title of ‘Caliph’: shewing its antiquity, validity, and universal acceptance Author: Red house, James W. (James William) Source: Foreign and Commonwealth Office Collection, (1877) Published by: The University of Manchester, The John Rylands University Library

[v] Correspondence passed between His Highness Aali Pacha, Minister of Foreign Affairs, of the Sublime Porte, and the Honorable P. E. De Roubaix, Esq., Consul General of the Sublime Porte, Cape of Good Hope: Aali Pacha, Petrus Emanuel de Roubaix\J. H. Hofmeijr [printers], 1871

[vi] Pages from the Cape Muslim history by Yusuf Da Costa; Achmat Davids , P. 82- Cape Town-1994

[vii] Traditional Turkish Hat which used in Turkish lands until the decline of the Ottoman Empire. The fez, in Turkish fez, is a felt hat either in the shape of a red truncated cone or in the shape of a short cylinder made of kilim fabric. Both usually have tassels. The fez is largely believed to be of Moroccan origins and later spread to the Ottoman Empire where it was popularized.

[viii] Gençoğlu, Halim. 2017. Ottoman traces in Southern Afrika the impact of eminent Turkish emissaries. Libra

[ix] Words the Cape slaves made: A socio-historical-linguistic study Achmat Davids*Department of Afrikaans, University of Natal, Durban 4001, Republic of South Africa Received October 1989.

[x] Gençoğlu, Halim. (2020) Last Ottoman consul in Mauritius, Muhammed Dawjee Effendi, https://twitter.com/halimgencoglu/status/1262067558582308865 , 21 May 2021.

[xi] South African Advertiser, 13 February of 1867, Malay Celebration of the Sultan’s Birthday.

[xii] Islam and Toleration: Studying the Ottoman Imperial Model Author: Karen Barkey, Reviewed work(s): Source: International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 19, No. 1/2, The New Sociological Imagination II (Dec. 2005), pp. 5-1

Leave a Reply