When the French cinema historian Georges Sadoul said, “After the invention of the cinema, in 1960, there is to my knowledge not a single true feature length African film production – acted, photographed, written, conceived, edited, etc. by Africans and in an African language.” This had been said almost 65 years after the beginning of the history of the seventh art. It was back in the 1960s, and until that day there had been some important steps taken in the art of cinema, many movements had emerged and the cinema had been growing stronger more than ever.

The old continent of Africa has met the youngest branch of art, the cinema, relatively recently and in order to make such a film, as Sadoul vaguely described, colonialism over the continent had to cease. African countries had to be liberated from Western-white rule and had to gain their own independence. Cinema was, of course, very well-known across the African continent; the Westerners had recorded many movies in this geography and established many cinema theaters. The British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish and Belgian overlords had implemented a “colonial cinema culture”, where stories and sceneries from “the civilized and modern life” were being displayed to the colonized nations. Cinema was known quite well, as a very important tool for the “development” and “Christianization” of the Africa.

The “civilization” mission of cinema

The first steps of the seventh art in Africa started in 1900s with a number of filmmakers, mostly with the Lumière brothers giving a perspective of the life in Africa, with recorded visits to Africa by European monarchs and leaders, and with the screening of the movies shot in colonial territories of modern-day Senegal, Guinea and Ivory Coast at an exhibition in Marseille in 1906. The harsh working conditions in the mineral mines were caught on camera and screened with a sugarcoating, while the hunting and safari tours also appeared on the screen as another African reality. With the ongoing political and military actions by the West, cinema had also begun to rule over this vast continent as an “ambassador for civilization”.

The movie “How a Letter Travels from the Great Lakes of Central Africa to us” (Lettre Nous Parvient des Grands Lacs d’Afrique), directed by Alfred Machin (1877-1929), a French director and actor known for his “progressive” views in films during this period, has caused great resonance. The 1911 film tells the story of a letter handed over to two locals that are rowing in their canoes in the marshes of Africa. The letter then crosses the deserts in caravans and boards ships and trains to reach the proper address in Europe. The movie is a typical illustration of the white man’s definition of civilization, referring to the system he had managed to establish. The movie named “How to Travel in Africa” (Come Si Viagga in Africa) by the Italian cinematographer Roberto Omegna, is filmed in Ethiopia in the same year and carriers lots of hints to Italian ambitions on the continent in the pre-Mussolini era.

Africa being evaporated on screens

In the “colonial movies” of an era that also covers the First World War, the common theme is mostly wrapped around the view Africa needs Europe, that the colonial motherland and the overseas colonies are inseparable, and that these African territories are part of a greater empire. In this context, an emphasis is laid on that white people are generous and civilized, whereas the black people are unforgiving and savage. This notion is repeated over and over again. Even in the most unbiased productions with the most humanist approach, Africa does not get further than being a decorating landscape. Its existence, its realities, its history and culture are confined to the white man’s point of view, and thus, the continent’s content is basically evaporated.

After World War II, the colonial empires began to cease and – with the rise of independence movements in African countries, the phenomenon called “colonial cinema” started to change its form. Racist movies or those that either openly or secretly belittle the African people appeared less in the theaters, while African romanticism started to rise. An example for this romanticism, which gradually gained importance, are the Tarzan movies with the adventures of a white man who seeks refuge in the jungles of Africa and while trying to break off from his past.

African steps of national cinema

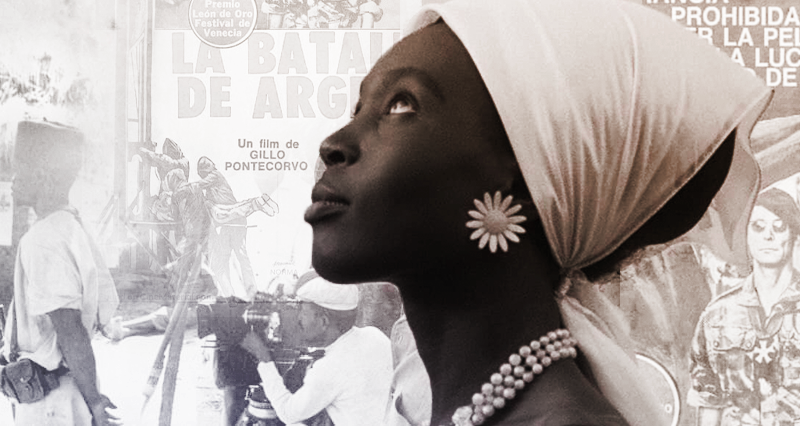

On the other hand, some domestic cinema productions had also started taking place throughout the countries that had just achieved independence. Algeria stands out as the country to take the first step in this aspect. The 1959 film “Algeria on Fire” (Algerie en Flammes) has a pioneering role, with depicting the day-to-day lives of the Algerian independence fighters and the conflicts they went through. The foundations of a nationalized cinema were being laid, as the country gained its independence in 1963 after an eight-year civil war. Movie theaters were nationalized, and the Algerian Cinematography Center and the Algerian Cinematheque were established in 1964. Domestic movies production has increased with the support of some progressive intellectuals such as Henri Langlois, the founder of French Cinematheque. With the nationalization of Western movie distribution companies, the Algerian national cinema took its place on the pages of history as an example to many other countries. The Algerian cinema achieved a much clearer identity with movies made by filmmakers such as Mustapha Badie, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina and Ahmed Rachedi. The awards won over some prestigious international film festivals such as Cannes and Venice are also very important in this regard. The iconized movie called “The Battle of Algiers” (La Battaglia di Algeri), an Italian-Algerian co-production movie directed by the Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo in 1966, maintains its importance as a symbolic movie on the Algerian War of Independence.

Although it gained independence in 1956, Tunisia kept on being a playground for French moviemakers and continued a Western-influenced cinema culture. In spite of that, the Carthage Film Festival (also known as the Cinema Days of Carthage), was established in Tunisia in 1966, and together with the movie called “The Dawn” (Al-Fajr) recorded the same year, provided great support to efforts of establishing national cinemas. The movie directed by Omar Khalifa, also regarded as the first example of modern Tunisian cinema, tells the story of the murder of three young resistance fighters in the final days of the French colonial rule, and the story ends with Habib Bourguiba entering Tunisia.

Morocco, the home of the city Casablanca, a city that has left deep traces in the history of cinema, had experienced the same excitement of the nationalized cinema movements with rather musical-cheerful examples, unlike the political realism movies in Algeria or Tunisia. Souheil Ben-Barka’s movies called “A Thousand and One Hands ” (Alf Yad wa Yad, 1972), which is about how the carpet makers are exploited, and the movie “There Will Be No Oil War” (Harb-al Petrul lan Takun, 1975), which was censored for criticizing the conducts of the oil companies, are considered the first realist productions within the Moroccan cinema.

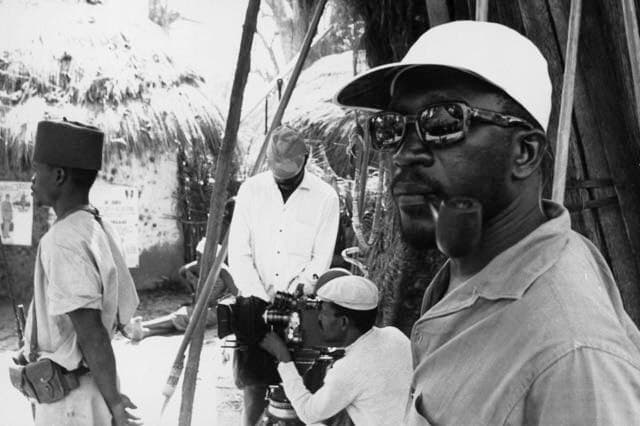

The story and vanguard work of Sembène

And the first ever director from the sub-Saharan Africa to gain an international recognition and the first person to ever realize an African production of the kind that Sadoul describes, as mentioned at the beginning of this article, will be the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007). The life story of Sembène, who had been one of the most important representatives of the post-colonial African cinema, is also interesting and colorful enough to become a movie of its own.

Unlike many filmmakers on the continent, Sembène did not receive an upper-class education and mostly worked as a mechanic or as a mason in his childhood and early youth. He then served in various branches of the Free French Forces, against the Nazi Germany in the World War II. Sembène played an active role in the railway workers’ strike in Senegal in 1947, started working in an automobile factory in Paris in 1948, then worked at the docks of Marseille, and slowly began to gain fame among the authors and writers by first writing a novel in 1956.

However, he thought that cinema was a much more convenient method to address the masses than literature, so he went to Moscow in 1961 to study cinematography and practiced at the Gorky Film Studio along with the theoretical education. After returning to his country Senegal, Sembène wrote and directed his first movie in 1961, after directing two short films: the movie called “Black Girl” (La noire de…), the story of a young Senegalese girl working as a housemaid in France, received great attention. Recorded in a documentary-like style, the movie combines the solitude and despair of the protagonist with the harsh realities of Senegal, reflecting the inner world of a person who is working in the world of colonial overlords, even if her country was no longer an overseas colony. Ousmane Sembène, who adapted his novel of the same name to the screens, has achieved a cinematographic immortality of some sorts, as the artist who first lit the ever-burning fire of the seventh art in Africa, by taking the first major step in a country without a film industry, and the first step across this vast continent.

Our famous poet Can Yucel once said, “If I had ever written a verse/continent like Africa, I would not wait one more second and die right away”. However, the filmmakers such as Sembène, who had “written” the African continent on the movie screens and their successor generations, have achieved immortality.

Leave a Reply