The White House has appointed a new Special Advisor for Africa Strategy at the National Security Council. Judd Devermont started the work in early October. He is expected to draw a new Africa strategy for the Biden Administration.

Devermont is not new to the White House. After having started in the State Department in 2001, he worked as foreign policy analyst for the US government between 2002 and 2011 and became Director for African Affairs in the National Security Council from 2011 to 2013 during the Obama administration.

From 2013 to 2015, Devermont worked as senior foreign policy analyst for the government and was National Intelligence Officer for Africa within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the institution that oversees the US intelligence agencies from 2015 to 2018.

In July 2018, Devermont left the official duties and became Director of the Africa Program in the thank tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and a lecture at the George Washington University.

Until now, the Biden administration has not deemed great importance to Africa, observes Amy MacKinnon from Foreign Policy, noting neither Biden nor any other top official has visited any African country since inauguration, and that Biden also has not met any African leader during recent UN General Assembly in New York.

She observes that till today, the Biden administration has mainly been focused on Ethiopia and Sudan.

Devermont pronounces a similar observation in a recent interview from June 2021, where he states that since his election, Biden has called only one African leader, while the Chinese President Xi had talked to three leaders from the continent.

So, what are the ideas of Judd Devermont, whom Foreign Policy expects to “jump start Biden’s Africa strategy”, a continent where the United States “has been on the sidelines – at least for the last four years” according to Devermont himself.

His point of departure is the US claim of global government, where “there will be an African dimension to every global challenge”, says Devermont in the interview cited above. His reason for that: The African population of currently 1.3 billion will double until 2050, and African countries are the largest bloc in the UN General Assembly.

Hence, addressing topics such as climate change, the pandemic, Internet piracy, “you need to involve Africans”. Besides, there are important economic possibilities awaiting US companies in Africa, says Devermont, which need to be “communicated to them” by the US government: “make sure that we are helping the US private sector thinking about the trade-offs. Why does it make sense to invest in in Nigeria versus New Zealand?”

But currently, the US Africa Policy faces great problems. With Devermont’s example, “about half of the African countries defended China when Washington and like-minded allies condemned Beijing for human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang”.

Yes, China is a main issue for Devermont, as well as the growing Russian influence on the continent and counter-terrorism. Let’s take a closer look at the latter first, then examine his proposals concerning countering Russian and Chinese influence in Africa and finish with his expectations for Biden’s policy.

US counterterrorism strategy in Africa

Devermont has given a statement to the House Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on National Security in December 2019, pronouncing goals and strategies for US counterterrorism efforts in Africa.

He summarizes the threats to US national security as follows:

“(1) Risks to U.S. persons, facilities, and financial interests in the region; (2) costs to U.S. taxpayers to finance peacekeeping and humanitarian relief missions; and (3) damage to U.S. leadership and influence because U.S. allies and adversaries perceive that the United States is disengaging.”

Going beyond security of objects and investment, Devermont’s threat definition includes a reference to great power competition on the African continent. In logical consequence, his proposals for countering terrorism overlap with his ideas on struggling against Chinese and Russian influence, as will be seen below.

Devermont proposes 4 points in his testimony:

1. “Invest in defense institution building”

Instead of focusing on “specialized units”, Devermont calls to seek cooperation and aid to “broader uniformed and civilian security architecture” including African police forces, where “money and training” should be increased.

2. “Tackle state fragility and politics”

Based on the assumption that terrorist threats develop from domestic circumstances, Devermont proposes, “to grapple with the domestic political incentives and disincentives that discourage responses to counterterrorism threats”. In other words, he stands for intervention into politics to achieve results according to the goals mentioned above.

Consequently, he cites the examples of Mali and Nigeria, “where there is little political will to respond constructively to the security threats”. The expression “constructively” may reflect these government’s quest for different allies in the struggle against terrorism, and moves them close to become a “threat themselves”.

3. “Stand up for human rights and democracy”

If African governments choose different countries as allies against terrorism, as recently is happening for instance in Mali or Ethiopia, then the US invokes accusations of human rights violations. Candidates in Devermont’s 2019 testimony were Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mozambique and Nigeria.

“If a government is guilty of gross human rights violations, it is in the US interest to withhold assistance as well as work with authorities to take all necessary corrective steps to resume engagement”, says Devermont.

4. “Broaden the international and domestic coalition”

Given the general tendency towards ‘America First’ policies and the according US retreat, Devermont states that “the United States is neither capable nor suited to lead the response to every terrorist and security challenge”, proposing to “recruit more foreign and domestic partners (…) even non-traditional partners”. His examples are Indonesia and Malaysia.

Additionally, Devermont proposes “engaging” African media, legislators, judges and “civil society stakeholders in the fight against terrorism”.

In the same statement concerning counterterrorism, Devermont says, “Russia and China have moved into the region to proffer themselves as an alternative to the United States. Russia has signed defense agreements with Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger.”

So let us take a look at his proposal how to counter Chinese and Russian influence.

Countering China

The odds against China are not well. As mentioned, Biden has had much lesser diplomatic contact with African countries than his counterpart, Xi Jinping. Concerning economics, “there isn’t much of a US alternative to what China offers African countries. China’s trade with Africa in 2020 was $180 billion. US trade with Africa in that same period was about $32 billion”, says Devermont in his interview.

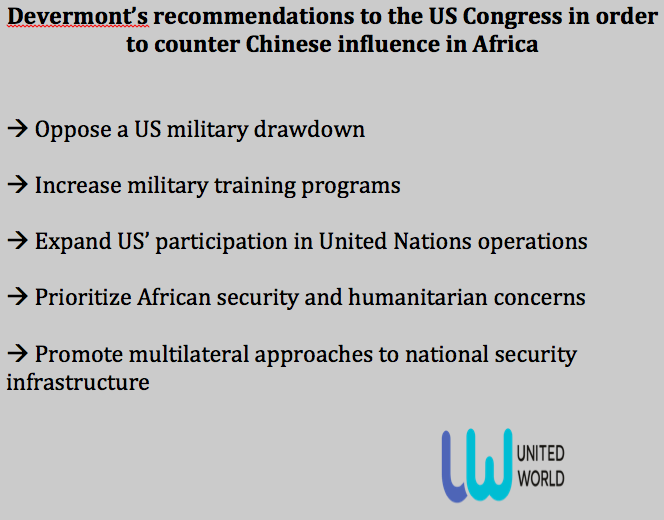

Devermont provides an insight of his views on China’s acitivities in Africa and the countering strategy in testimony before the U.S. – China Economic and Security Review Commission delivered in May 2020.

According to Devermont, Chinas has – beginning in the 1990s and accelerating in the 2010s – increased its military presence in Africa within UN peacekeeping missions, advanced its security cooperation with African countries, engaged in critical infrastructure projects and progressed multilateral diplomatic initiatives.

Devermont warns that, “African leaders want more, not less, engagement from China”, hence, “US condemnation of Chinese engagements, especially peacekeeping, military exercises, or training will be poorly received by African counterparts”.

Same picture in the Africa-Chinese economy cooperation: “We have to examine each case on its own merits and understand that Africans overwhelmingly approve of Chinese investments.”

Devermont’s proposals are presented below and rely heavily on strengthened military activities. In reverse, terror activities on the African continent will provide the US also in future with occasions to deepen its footprint on the continent, if Devermont’s proposals are realized.

The idea to increase military training programs is taken from the Strategy of Counterterrorism and reflects the intention to control more thoroughly African national armies, also forecasting they will have a key role in politics.

These also reflect the lack of economic leverage, which the US has over African countries. Here, Devermont calls the State Department to gather African countries and US allies – such as France, Germany, India Japan, United Kingdom and the UAE – “to formulate guiding principles for foreign investment in critical infrastructure”.

Additionally, the US “should press – in partnership with multilateral development banks – for financing of some critical infrastructure as well as establishing monitoring boards for foreign investments”.

Still, the US needs to distinguish between “projects that are benign and those that are more threatening to US interests”, testifies Devermont.

His strategy aims to limit the Chinese influence to the current level, while permitting possible positive investments. It lacks the background of a strong, manifest US interest with a desired order.

Next headache: Countering Russian influence

And there is Russia with growing economic and security activity in Africa. In a long article from October 2019, Devermont suggests 5 recommendations to counter it. The article has been published right ahead of the first Russia-Africa summit.

“It is imperative to shut down Russia’s current rising tide of influence in Africa, especially where the Kremlin seeks to weaken ties between the United States and its partners”, writes Devenport.

1. “Act before the Russians”

First Devermont argues , should the US “act before the Russians”, adding that future geography of Moscow’s activity is predictable along certain factors: a country rich of mineral resources, heading to question influence of Western actors, experiencing political strife and being geopolitically important is according to Devenport likely to be Moscow’s target, and he names Nigearia, Madagascar, Ethiopia, the Sahel Zone and Mozambique as examples. Here, the US should “preempt or at least minimize opportunities for Russian engagement”.

2. “Isolate, not elevate Russia’s profile in Africa”

Secondly, proposes Devermont, should the US “work rhetorically to isolate, not elevate Russia’s profile in Africa”. He “calls American politicians and commentators not to describe (Russia) as having a starring role in the continent.”

3. Positive engagement with African countries

In continuations of the second point, the US should refrain from describing the situation in Africa as great power competition, because “African elites recognize that geopolitical rivalry increases their country’s strategic importance and they expect to profit from a surge in US engagement”.

Instead US engagement and investment should be increased within bilateral relations, writes Devermont.

4. US and UN sanctions

Prospecting a partly failure of these points, Devermont proposes to “aggressively enforce US and UN sanctions (…) to deter African governments from working with sanctioned individuals and Russia’s defense and intelligence sector”.

Mentioning that the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) may be applied, Devermont cites a proposal of Joseph Siegle to treat Russian private military contractors as “organized criminal syndicates”.

5. Challenge Russian propaganda on the continent

Lastly, Devermont proposes to challenge what he calls “Russian propaganda efforts on the continent” – activities of Russian universities, media like Russia Today and nongovernmental organizations – whereas the US “could use its own plattforms to increase awareness of Russia’s destabilizing activities, as it did during the Cold War”.

In summary, Devermont says: “The US playbook for responding to the Russian threat is clear: strengthen ties with African leaders and civil society, expose Russia’s subversive activities, and block new opening for Moscow to gain sway in the region.”

Working in a team with an uncertain weight

Devermont has been appointed to draw a new Africa strategy, and of course, he will work within institutions.

He expressed the “restoration of a previous approach to the continent in terms of public diplomacy and governance”, with climate change addressing the pandemic, supporting the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and of course security issues, in an article published in February 2021.

The Biden administration is still putting together the team for Africa policy, with Molly Phee, former ambassador to Sudan, approved as Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of African Affairs on September 30, after a long resistance by the Senate.

Phee embarked on October 16 to her visit to Africa, heading to Ghana and Burkina Faso.

Whether African issues will gain weight within the Biden administration and be more of a priority compared to the Trump era? “Only time will tell” says Devermont.

Leave a Reply