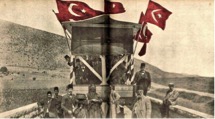

Railroads to Hejaz (left) and Cairo

On one side, the Hejaz Railway project, led by the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid, aimed to link the capital of the state Istanbul and the Muslim world as far as Red Sea. To support this project, apart from contributions from thousands of Ottoman citizens, aid also came from Muslims communities in the world. Donations were mainly made by Muslims of India, Egypt, Russia and Morocco, as well as Indonesia, Singapore, South Africa, Mozambique, as well as some Islamic societies in Europe, Tunisia and Algeria. Aid for Hejaz Railway came from Muslim leaders and administrators such as the Moroccan Emir, the Shah of Iran and the Emir of Bukhara. This wide participation was a sign that the Hejaz railway project was adopted by all Muslims around the world.i In order to reward the donors, with the advice of Izzet Pasha, nickel, silver and gold Hejaz railway medals were created and given to the donors. These medals played an important role in motivating the public for donations.ii

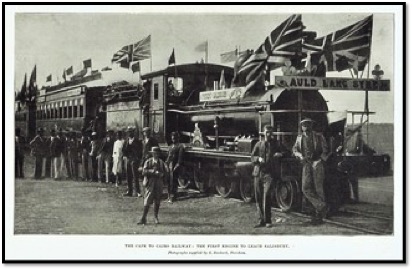

On the other side, another Railway Project led by the English colonialist Cecil John Rhodes aimed at colonising the entire African continent from Cape to Cairo. Rhodes did not only exploit the resources of African nations but also ill-treated the natives who worked in his railroad project by force. His famous desire was to be able to draw a “red line” from Cairo to Cape Town, building a railway across the entire continent without ever leaving British territory. Critics now point to his time as prime minister of the Cape Colony, from 1890 to 1896, as the period when his government systematically restricted the rights of Black Africans by raising the financial qualifications for voting rights. Rhodes wanted to create an international movement to extend British influence. These two projects of the nineteenth century can provide us with sufficient clue to shed light on the intentions of the two nations in history.iii

Two great projects run by two different nations with two completely different goals.

Hejaz Railway

The main purpose of Hejaz railway project was to establish a connection between Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire and the seat of the Islamic Caliphate, and Hejaz in Arabia, the site of the holiest shrines of Islam and the holy city of Mecca, the destination of the annual Hajj pilgrimage. Another important reason was to improve the economic and political integration of the distant Arabian provinces into the Ottoman State, and to facilitate the transportation of military forces. Railways were experiencing a building boom in the late 1860s, and the Hejaz region was one of the many areas up for speculation. The first such proposal involved a railway stretching from Damascus to the Red Sea. This plan was soon dashed however, as the Amir of Mecca raised objections regarding the sustainability of his own camel transportation project should the line be constructed. Ottoman involvement in the creation of a railway began with Colonel Ahmed Rashid Pasha, who, after surveying the region on an expedition to Yemen in 1871–1873, concluded that the only feasible means of transport for Ottoman soldiers traveling there was by rail. Other Ottoman officers, such as Osman Nuri Pasha, also offered up proposals for a railway in the Hejaz, arguing its necessity if security in the Arabian region were to be maintained.iv

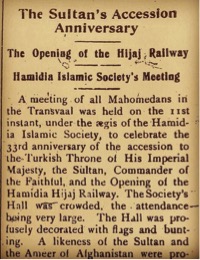

Many around the world did not believe that the Ottoman Empire would be able to fund such a project which was estimated to cost around four million Turkish lira, a sizable portion of the budget. The Ziraat Bankasi, a state bank which served agricultural interests in the Ottoman Empire, provided an initial loan of 100,000 lira in 1900. This initial loan allowed the project to commence later the same year. Sultan Abdulhamid II called on all Muslims in the world to make donations to the construction of the Hejaz Railway. The project had taken on a new significance. Not only was the railway to be considered an important military feature for the region, but it was also a religious symbol. Hajis, pilgrims on their way to the holy city of Mecca, often didn’t reach their destination when travelling along the Hejaz route. Unable to contend with the tough, mountainous conditions, up to 20% of hajis died on the way. Sultan Abdulhamid was adamant that the railway stand as a symbol for Muslim power and solidarity which would make the religious pilgrimage easier not only for Ottomans, but all Muslims. As a result of this, no foreign investment in the project was to be accepted. The Donation Commission was established to organize the funds effectively, and medallions were given out to donors. Despite propaganda efforts such as railway greeting cards, only about 1 in 10 donations came from Muslims outside of the Ottoman Empire. One of these donors, however, was Muhammad Inshaullah, a wealthy Punjabi newspaper editor. He helped to establish the Hejaz Railway Central Committee. Access to resources was a significant stumbling block during construction of the Hejaz Railway.v Water, fuel, and labour were particularly difficult to find in the more remote reaches of the Hejaz. In the uninhabited areas, camel transportation was employed not only for water, but also food and building materials. Fuel, mostly in the form of coal, was brought in from surrounding countries and stored in Haifa and Damascus. Labour was certainly the largest obstacle in the construction of the railway. In the more populated areas, much of the labour was fulfilled by local settlers as well as Muslims in the area, who were legally obliged to lend their hands to the construction. This forced labour was largely employed in the treacherous excavation efforts involved in railway construction. In the more remote areas, a more novel solution was used. Much of this work was completed by railway troops of soldiers, who in exchange for their railway work, were exempt from one third of their military service.vi

As the rail line traversed treacherous terrain, many bridges and overpasses had to be built. Since access to concrete was limited, many of these overpasses were made of carved stone and stand to this day.vii Many Muslims supported the projects and received Hedjaz Railway Medals from the Ottoman government. Imam Abdulkader Bazer of Johannesburg, Osman Ahmed of Durban and Hesham Neamatollah Effendi of Cape Town were the most prominent Muslim figures in Southern Africa to advertise the project among the Muslims in their regions.viii

Under the supervision of chief engineer Mouktar Bey, the railway reached Medina on 1 September 1908, the anniversary of the Sultan’s accession. In 1913 the Hejaz Railway Station was opened in central Damascus as the starting point of the line and celebrated by Muslims from Asia to Africa.ix

Cape – Cairo Railway

The original proposal for a Cape to Cairo railway project was made by Edwin Arnold to discover the course of the Congo River in 1874. The proposed route involved a mixture of railway and river transport between Elizabethville, now Lubumbashi, in the Belgian Congo and Sennar in the Sudan rather than strictly by rail. This plan was initiated at the end of the 19th century, during the time of Western colonial rule, largely under the vision of Cecil Rhodes, in the attempt to connect adjacent African possessions of the British Empire through a continuous line from Cape Town, South Africa to Cairo, Egypt. The railway is connected to the Mozambican, Zimbabwean and South African systems through the Beira-Bulawayo railway, the Limpopo railway, and the Pretoria-Maputo railway, reaching the ports of Maputo and Beira. British interests had to overcome obstacles of geography and climate, and the competing imperial schemes of the French and Portuguese mentioned above and of the Germans. In 1891, Germany secured the strategically critical territory of German East Africa, which along with the mountainous rainforest of the Belgian Congo precluded the building of a Cape to Cairo railway.x

In 1916 during World War I. British and British Indian soldiers won the Tanganyika Territory from the Germans, and, after the war, the British continued to rule the territory, which was a League of Nations mandate from 1922. The continuous line of colonies was complete. The British Empire possessed the political power to complete the Cape to Cairo Railway, but economics, including the Great Depression of the 1930s, prevented its completion before World War II After World War II, the decolonisation of Africa and the establishment of independent countries removed the colonial rationale for the project and increased the project’s difficulty, effectively ending the project.xi

Cecil John Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his British South Africa Company founded the southern African territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), which the company named after him in 1895. South Africa’s Rhodes University is also named after him. He also devoted much effort to realising his vision of a Cape to Cairo Railway through British territory. Rhodes set up the provisions of the Rhodes Scholarship, which is funded by his estate. Rhodes dreamed of a “red line” on the map from the Cape to Cairo. Rhodes had been instrumental in securing southern African states for the Empire. He and others felt the best way to “unify the possessions, facilitate governance, enable the military to move quickly to hot spots or conduct war, help settlement, and foster trade” would be to build the “Cape to Cairo Railway.xii

Rhodes wanted to expand the British Empire because he believed that the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to greatness. In what he described as “a draft of some of my ideas” written in 1877 while a student at Oxford, Rhodes said of the English, “I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for humanity. I contend that every acre added to our territory means the birth of more of the English race who otherwise would not be brought into existence.”xiii In the late 19th century, the British-South-African personality Cecil Rhodes dreamed of a complete, uninterrupted railway stretching from Cape Town, South Africa, all the way to Cairo, Egypt. During Rhodes’s lifetime, the railway extended as far north as modern-day Zimbabwe – which was in that era known by its colonial name Rhodesia. A railway traversing the entire north-south length of Africa was an ambitious dream, for an ambitious man.xiv

Cape – Cairo was a proposed intercontinental railway. Under this plan, the city and the port of Cairo located on the northern end of the Nile River in Egypt in the north-east of Africa are planned to be connected by railways to Cape town at the southern end of south Africa. This route will be approximately 14000 km long. This railway proceeds through Zimbabwe’s city Bulawayo in the south to Pretoria the capital of South Africa and goes to Cape town, through the well-known towns of Johannesburg and Kimberley. Due to dense forests and high downhill areas, the traffic in this port is completely undeveloped. Upon completion of the proposed Cape Cairo Railways, African territories from north to south will have mutual relations and this will help in their economic development.xv

Starting from the south, the first section of the road that runs through South Africa is called the N1, linking Cape Town in the south with Beit Bridge on the Limpopo River between South Africa and Zimbabwe. It passes through Johannesburg and Pretoria. There are numerous alternative routes in South Africa, including a route through Mafikeng and Gaborone, as an alternative to reach Zimbabwe.xvi The alternative route continues as the T1 Road in Zambia towards Lusaka. From Lusaka, Zambia’s Great North Road continues the route to Tanzania as the T2 Road.xvii

In Tanzania there are a number of roads that could be deemed to be part of the route; the clear definitions and markings that are characteristic of the Pan-African Highway do not apply here. Most would consider it to be the road from Tunduma on the Tanzania-Zambia border, through Morogoro to the Arusha turnoff, and north through Dodoma to Arusha, then to Nairobi in Kenya. This route is now all paved. There was a marker in the 1930s in Arusha, Tanzania, to indicate the midpoint of the road. The entire route through Tanzania from Tunduma on the Zambian Border to the Kenya Border is designated as the A104 Road. Kenya has a tarred highway to its border with Sudan but the roads in southern Sudan are very poor and made frequently impassable, so that even without the conflicts that have afflicted Sudan, the route through Ethiopia is generally preferred by overland travellers. The route from Isiolo in Kenya to Moyale on the Ethiopian border through the northern Kenyan desert has sometimes been dangerous due to bandits but is now paved. Through Ethiopia the route is tarred but some sections may have deteriorated severely. A paved road from Lake Tana to Gedaref takes the route into Sudan.

The most difficult section in the whole Cape to Cairo journey was across the Nubian Desert in northern Sudan between Atbara and Wadi Halfa, but this has been bypassed by a paved road on the west side of the Nile, Dongola-Abu Simbel Junction-Aswan. Tarred highways continue the route to Cairo. As a result, the Cape to Cairo Road is fully paved. Firstly, the Cairo–Cape Town Highway passes through Addis Ababa, Ethiopia while the Cape-to-Cairo Road goes directly through South Sudan from Kenya. Secondly, the Cairo–Cape Town Highway passes through Livingstone, Victoria Falls, Bulawayo, Francistown, and Gaborone and not through Harare, Pretoria and Johannesburg. This new route has a length of 10,228 km. As South Sudan has a paved link to its border with Kenya, ultimately a route through southern Sudan via Khartoum and South Sudan may provide a shorter alternative to the Ethiopian route.xviii

It was planned as a link between Cape Town in South Africa and Port Said in Egypt. South Africa was not originally included in the route, which was first planned in the Apartheid era, but it is now recognized that it would continue into that country. The consultants’ report suggested Pretoria as the end, which seems somewhat arbitrary and as a major port, Cape Town, is regarded as the southern end of regional highways in Southern African Development Community countries. The highway may be referred to in documents as the Cairo–Gaborone Highway or Cairo–Pretoria Highway.xix

Notes

i Gençoğlu, Halim. 2017. Ottoman traces in Southern Afrika the impact of eminent Turkish emissaries. Libra.

ii Özyüksel, Murat. 2016. The Berlin-Baghdad Railway and the Ottoman Empire: industrialization, Imperial Germany and the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

iii Wood, Richard. 1991. “Cecil John Rhodes”. Heritage of Zimbabwe. (10): 123-130.

iv Tourret, R. 1989. Hedjaz railway. Oxon, G.B.: Tourret Publishing.

v Muh̄amad The history of the Hamidia Hedjaz railway project in Urdu, Arabic and English. Lahore: Printed at the Central printing works.

vi Hicaz demiryolu ; Hicaz demiryolunun varidat ve mesarifi ve terakki-ı inşaatı ile hattıin ah-val-i umumiyesi hakkıinda malûmat-ı ihsaiye ve izahat-ı lâzimeyi muhtevidir. 1908. [Istanbul]: Evkaf-ı Islâmiye Matbaası.

vii On the other side, the Emir Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca viewed the railway as a threat to Arab suzerainty, since it provided the Ottomans with easy access to their garrisons in Hejaz, Asir, and Yemen. From its outset, the railway was the target of attacks by local Arab tribes. These were never particularly successful, but neither were the Turks able to control areas more than a mile or so either side of the line. Due to the locals’ habit of pulling up wooden sleepers to fuel their campfires, some sections of the track were laid on iron sleepers.

viii Gençoğlu, Halim. 2020. Ottoman cultural heritage in South Africa: Islamic legacy of the Ottoman Empire at the tip of Africa (archival records, photos and documents) Güney Afrika’da Osmanlı kültürel mirası : Osmanlı imparatorluğu’nun Afrika’nın ucundaki Islam mirası (arşiv kayıtları, resimler ve belgeler). Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları.

ix In September 1907, as crowds celebrated the rail reaching Al-‘Ula station, a rebellion organized by the tribe of Harb threatened to halt progress. The rebels objected to the railway stretching all the way to Mecca; they feared they would lose their livelihood as camel transport was made obsolete. It was later decided by Abdulhamid that the railway would only go so far as Medina.

x Oxford University Press. 1967. E. Africa: Cape to Cairo [Oxford].

xi Landau, Jacob M. 2017. The Hejaz Railway and the Muslim Pilgrimage: a Case of Ottoman Political Propaganda.

xii Lockhart, John Gilbert, and C. M. Woodhouse. 1963. Cecil Rhodes. New York: Macmillan.

xiii Rhodes’s views on race have been debated; he supported the rights of indigenous Africans to vote, but critics have labelled him as an “architect of apartheid” and a “white supremacist”, particularly since 2015.

xiv In honour of Rhodes, whose statesmanship and entrepreneurism made its founding possible.

xv Copeland, Mike. 2003. Cape to Cairo. Llandudno, South Africa: Sunbird Pub.

xvi Bruce, Alexander. 2011. Cape to Cairo. [Place of publication not identified]: British Library, Historic.

xvii No alternative route; Also known as the Tanzam Highway and consisting of a right turn at Kapiri Mposhi towards Tanzania.

xviii Great Britain. 2008. British South Africa Company. Correspondence with Mr. C.J. Rhodes relating to the proposed extension of the Bechuanaland Railway. Cambridge [England]: Proquest LLC.

xix Weinthal, Leo. 1923. The story of the Cape to Cairo railway & river route from 1887 to 1922. London: Pioneer Pub. Co.

Leave a Reply