Stephanie Williams, the UN’s Special adviser on Libya, visited Cairo, Ankara and Moscow. Earlier, the UN official has held meetings with key internal Libyan players. Now, Ms. Williams seeks to position herself as if she is the one who decides how and in what form the political process in Libya will proceed. So it was her who announced that the presidential elections scheduled for last December were being postponed to June.

We can observe a paradoxical situation, when a former American diplomat dictates to former field commanders how to behave in Libya. Ostensibly, she represents the international community. But has the work of UN structures in Libya anything to do with the international community or the interests of the Libyans themselves?

Senseless “parasites”

The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) was established in 2011. At that time, NATO forces invaded Libya and deposed the country’s leader, Muammar Gaddafi, who was later brutally murdered without trial. According to a UN Security Council resolution (UNSCR 2009), UNSMIL’s mandate was limited to the following areas:

(a) Restore public security and order and promote the rule of law;

(b) Undertake inclusive political dialogue, promote national reconciliation, and embark upon the constitution-making and electoral process;

(c) Extend state authority, including through strengthening emerging accountable institutions and the restoration of public services;

(d) Promote and protect human rights, particularly for those belonging to vulnerable groups, and support transitional justice;

(e) Take the immediate steps required to initiate economic recovery; and

(f) Coordinate support that may be requested from other multilateral and bilateral actors as appropriate.

UNSMIL’s mandate has subsequently been renewed several times. Its current mandate is stipulated by the latest UN Security Council Resolution 2542 (2020), which extended UNSMIL’s mission as an integrated special political mission. However, none of the UN efforts have brought the country any closer to unification. The most important issues of political dialogue were solved without the UN and UNSMIL, including, for example, attempts at negotiations between the parties, unblocking the blockade of Libya’s oil exports, etc. The UN was only involved in the negotiation processes initiated by others, which did not always lead to a good result.

As Khaled al-Mishri, head of Libya’s High Council of State, said earlier to UWI, UNSMIL has been “not constructive since its beginning”.

The UN mission in Libya has acquired personnel and a budget, which UN bureaucrats are successfully absorbing. The result of their activities so far has been to embezzle money that goes out of the UN budget like into a black hole. Commenting on the role of UN Mission in Libya, Al-Mishri said in another interview that the UN and its missions are “parasites” that live on the crises of the third world, adding that the UN Mission in Libya did not provide any support and failed to achieve peace in the country.

Stephanie Williams – questionable legitimacy

It is interesting that the UNSMIL website and all of Stephanie Williams’ speeches make it sound as if she is the head of the UN Mission in Libya. In fact, she is not. Ján Kubiš, the head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya stepped down on November 23, 2021. Since then, the UN Security Council has been unable to agree on a replacement.

Then the UN Secretary-General António Guterres appointed Ms. Williams as Special Advisor on Libya. Thus, she was appointed to a position not covered by UNSCR 2009, bypassing the existing mechanisms of coordination with the members of the UN Security Council, not to mention other member countries of the organization.

Not a single UN Security Council resolution that refers to the mandate of UNSMIL mentions the position of a Special Adviser. Accordingly, Williams’ credentials are highly questionable from an international legal perspective.

How did Ms. Williams come to be in Libya in the first place? In 2018, Williams was the US chargé d’affaires in Libya. In that position, she took a special interest in Libyan oil, meeting with Libyan officials about the control of certain armed formations over oil sources.

In 2018, Williams was appointed to represent the UN Secretary-General António Guterres as his Deputy Special Representative for political affairs in the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). At the time, the French-speaking Geneva-based newspaper Tribune de Genève interpreted the appointment as follows: “The return of this list with previous works at the US embassy in Tripoli is evidence of the return of the US Department of State – at least behind the scenes – to take care of Libyan affairs.”

In 2020, Ghassan Salamé unexpectedly resigned and Stephanie Williams took over as head of the UN Mission in Libya. She organized the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF), which resulted in a National Unity Government headed by Abdul Hamid Dbeibah. Najla al-Mangoush, formerly of the U.S. Institute of Peace, became Minister of Foreign Affairs.

De facto, the U.S. has used UN mechanisms to consolidate its influence in Libya. It is important that, both then and now, Stephanie Williams has stood at the de facto head of UN institutions at times when they could have influenced the formation of Libya’s institutions of power. In both incidents, Ghassan Salamé and Ján Kubiš – the heads of the UN mission in Libya – have suddenly resigned unexpectedly to clear the way for Mrs. Williams. Williams was coming to the forefront and acted as an actor in reshaping the political map of Libya when some actors forced UN representatives, agreed upon by the international community, from their positions.

In December 2021, Ján Kubiš, speaking at the UN Security Council, said that despite his resignation letter he would like to continue to serve as UN representative in Libya for the duration of the electoral period. “In the resignation letter to the Secretary-General, I also confirmed my readiness to continue as the Special Envoy for a transitional period – and that in my opinion should cover the electoral period – to ensure business continuity provided that it is a feasible option,” Ján Kubiš said.

Nevertheless, the secretary general was in a hurry to accept his resignation, effective as of December 10, 2021.

And as early as December 12, Stephanie Williams arrived in Libya, “at the request of the Secretary-General,” as she admits herself.

Why was there such a hurry to appoint Stephanie Williams to Libya through the head of the UN Security Council, although the Special Envoy on Libya was ready to work during the transition and entire electoral period? Or was Stephanie Williams appointed to Libya precisely to prevent elections, extend the transition period, and prevent Libyans from electing a sovereign leadership?

Stephanie Williams’ secret connections

The answer can be found in Williams’ own biography. Georgetown University, where she received her master’s degree in 1989, lists her as Stephanie Ann Turco. In 1994, U.S. State Department records already show her as Stephanie Turco Williams.

Also in the traces that can be found on the Internet, we learn that Stephanie Ann Turco studied at Georgetown University on the Al-Sayyid Hassan Taher Scholarship, which is a certain Islamic foundation based in New York. The foundation itself is suspiciously almost silent about itself. More than anything, it looks like an intelligence tool for selecting talent. On the same scholarship a certain Thomas E. Williams, Jr. attended an elite American school in India – the Woodstock School. In a 2011 letter to her school’s alumni association, she writes that her husband’s name is Thomas and with whom they had two children living in Bahrain.

Ms. Williams’ first overseas assignment in 1994 was to Pakistan. Also in 1994, Thomas E. Williams, Jr. was transferred from the U.S. Embassy in Manama to Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs Bureau. During his time in Manama, Ms. Williams also worked in Bahrain.

On British Linkedin in 2015, Ms. Williams was listed as an employee of the U.S. Embassy in London.

At the same time, Tom Williams, former Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad, was working at the U.S. Embassy in London. He served as Political Minister Counselor in London. British Channel 4 wrote about his family: “career member of the Senior Foreign Service, Mr. Williams is married and has two children with his wife, Stephanie, who is also a Foreign Service Officer. His foreign language is Arabic. Coincidence?

This begs the following question: Why does not Stephanie Williams’ official biography on the UN website indicate that she worked at the American embassy in London? Does her husband still work for the U.S. government on a high position? Linkedin still lists him as deputy head of the U.S. diplomatic mission in Bahrain.

How can we talk about Stephanie Williams’ impartiality if she and her husband are staff members of the U.S. State Department?

Stephanie Williams also may be linked to the US intelligence. She received her master’s degree in national security in 2008 from the National War College. It is a privileged institution that graduates professionals working for U.S. intelligence agencies and armed forces. She previously worked in various positions in U.S. embassies in the Middle East and in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the U.S. State Department.

The latter is part of the U.S. intelligence community, charged with analyzing classified data.

In 2008, Stephanie Williams, as Office Director, Maghreb Affairs, U.S. Department of State, established contacts with Libya’s economic elites, including with Mahmoud Jibril, who would become Libya’s interim Prime Minister after 2011.

In 2011, Ms. Williams served as the chargé d’affaires of the United States in Bahrain during the events of the Arab Spring. At the time, the Bahraini government media accused her and Ambassador Ludovic Hood of interfering in the country’s internal affairs.

In 2017, Williams carried out U.S. contacts with the Syrian opposition. In general, she was thrown into those areas of work where U.S. oil interests and unstable regions were combined. Her and her husband’s contacts with Britain are also interesting.

Hate and Corruption

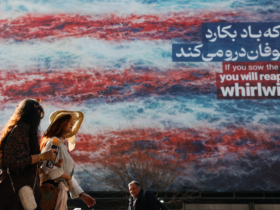

Stephanie Williams is hated in Libya. Thus, the residents of Bani Walid city declare that if Williams appeared in their city, they would “kill” her. According to the locals, Williams is “a NATO agent.”

Williams’ arrival in Libya also prompted an armed speech by field commander Salah Badi of Misrata, who said Williams “will not stay on our lands.”

The Libyans’ dislike of Williams is not just because she is a former (or current) member of the U.S. intelligence community and an American diplomat. Williams has been accused of making illegal deals with Libyan oil. Even during the Gadhafi era, Williams developed contacts with the Libyan business elite. Now Libyans are actually forced to sell oil through American traders. 35% of Libya’s oil goes through Tamoil, which is owned by the American company Colony Capital since 2007. Since the monopoly seller of Libyan oil is the National Oil Company of Libya, which Williams supports, there is no way the Libyans can change the scheme in which a significant portion of the oil revenue goes to the Americans.

Stephanie Williams also had promised to investigate all allegations of bribery and corruption at the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF).

However, no investigations were conducted.

On March 2 last year, a leaked UN report written by the Panel of Experts, an investigatory UN organ, revealed that interim prime minister Dbeibah had bribed several LPDF delegates to elect him Prime Minister. According to the report, two participants “offered bribes of between $150,000 to $200,000 to at least three LPDF participants” if they committed to vote for Dbeibah. Stephanie Williams, however, supported the new prime minister despite all the accusations and allegations of corruption.

And isn’t Stephanie Williams’ recent rejection of the need to withdraw foreign mercenaries from Libya related to corruption? She did not see the departure of foreign mercenaries as a “prerequisite for the elections”, although she had previously held a different view.

In December 2021-January 2022, Stephanie Williams tried to impose the UN support to the Dbeibah cabinet as a ready-made solution for Libya, which caused protests in the country. As Libyan MP Salem Kanan Williams noted, she had no right to set a date for elections in the country.

In the case of Stephanie Williams, she is not just a U.S. agent of influence, but also a skilled and experienced agent with high connections in both the United States and Libya, in the Arab Gulf and the Maghreb and in the United Kingdom. That is why she is again and again included in the critical issues of Libya exclusively in the interests of the U.S., for which she has been working for more than 20 years.

However, even the departure of Stephanie Williams from the UN structures in Libya will not solve the problem. The UN remains an extremely corrupt and ineffective body. This is especially true of peacekeeping and political missions. Take, for example, the recent scandal in which Portuguese UN peacekeepers in CAR were caught smuggling diamonds.

The UN Department of Political Affairs leads UNSMIL, which in turn is headed by American diplomats since 2007. The U.S. uses the UN peacekeeping and political mechanisms for its own purposes. Only a profound reform of the entire UN apparatus could solve the problem of Western domination of its institutions, as well as the problem of close ties between UN officials and mafia structures. Libya is an example of how UN institutions can often work in ways that do not serve the interests of the international community or the countries they are supposed to help.

Leave a Reply