In part one of the analysis of the Strategic Compass, I have focused on the political and geostrategic orientation of the European Union. My conclusion was that the EU was preparing for a foreign policy more limited in geography and more relying on military.

The following text dives into the details of the “Strategic Compass for Security and Defence”, as the document that has been approved by the European Council on March 21, 22.

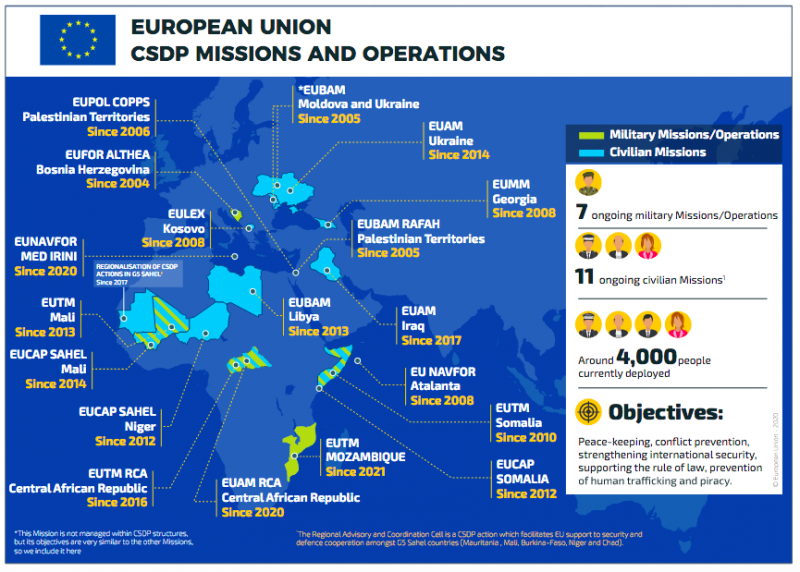

The European Union had already in place a so-called Common Defence and Security Policy (CSDP). Since 2002, The EU has, via its member states, pursued more than 30 military missions. It has currently over 4.000 troops engaged in running missions (Chart 1).

In the last years, the European Union has taken important steps to further militarize its foreign policy. In 2016, the EU Global Strategy was agreed upon. The so-called Permanent Structured cooperation (PESCO) was established in 2017, aiming to support arms development and procurement on union level as well as the establishment of multinational force groups. In the same year, the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) was agreed upon with the establishment of a permanent operation military headquarters in Brussels. Also in 2017, the European Defence Fund was introduced to develop a joint industrial base for defense and contribute to strategic autonomy.

It is therefore not surprising that the Strategic Compass announces a lot of “mores” and “strengthening” of an already given policy. But there are also qualitative changes.

The EU document is divided into the chapters “Act”, “Secure”, “Invest” and “Partners”. The aspect of partners has been dealt with primarily in the first article, so let us follow the other chapters. But instead of the EU’s titles, this article uses the categories centralization, aggression, militarization and domestic preparation.

1. Centralization

The conflict between Brussels and the member states is an endless story in the history of the European Union, and the Strategic Compass will introduce some new chapters to it. The reason is that it includes several serious elements of advancing EU competences and institutions on the cost of member states.

Detecting “power politics” and greater competition, as we have described in the first part, the Strategic Compass (SC) demands “greater flexibility in our decision-making process (…) including constructive abstention” (SC, p. 14, emphasis in original). The EU wants to “allow a group of willing and able Member States” to conduct their own missions within the CSDP. The European Union obviously expects that its future defense and security policy and actions might not “convince” all member states – but does not want to be stopped by that.

There are more steps concerning strengthening Brussels vis a vis member states and centralizing defense and security. The SC states “we must ensure that all EU defence initiatives and capability planning and development tools are embedded in national defence planning”, effectively submerging national defense policy to the community level (SC, 31, eio.). This measure is accompanied by an annual meeting of the Union’s Defence Ministers, while all Member states “must fulfill all binding commitments” within the PESCO by 2025 (SC 33).

Operational centralization takes place in the strengthening of the MPCC which shall “fully be able to plan, control and command non-executive and executive tasks and operations as well as live exercises” by 2025. This Brussels-based HQ, which in 2017 was responsible for non-executive operations in Somalia, Mali and the Central African Republic, shall in 2025 be able to pursue “two small-scale or one medium-scale executive operation (SC, 19) and “should be seen as the preferred command and control structure” (SC, 16) – preferred over national structures as well as NATO HQs[i].

This is nothing less than introducing a military command above the European nation states.

Explainer for executive vs. non-executive operations: The latter is a predominantly advisory military operation, while in the former the military conducts operations in replacement of the host nation.[ii]

The establishment of a Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity “in close cooperation with Member States’ intelligence agencies” is another moment of centralization.

2. Aggression

“The EU must become faster and more capable and effective in its ability to decide and act”, states the SC (13, Eio.). Above we have seen hat ability to decide leads to centralization of decision-making, intelligence gathering and military command as well as financing. “Act” means a much more militarily aggressive positioning of the EU.

The core element and novum is the introduction of a Rapid Deployment Capacity (RDC) of 5.000 troops to be used “in different phases of an operation in a non-permissive environment, such as initial entry, reinforcement or as reserve force to secure an exit” (SC, 14) commanded by the MPCC.

Operational scenarios for the RDC shall be agreed upon in 2022, live exercises are planned to take place starting in 2023, and in 2025, the force shall be fully operational.

“Non-permissive environment” is here maybe the euphemism of the year. Some state’s territory is named “environment”, and its rejection of the operation is called “non-permissive”. In clearer words: The European Union prepares a force of 5.000 soldiers to intervene invade a country partially.

There is indication as where the RDC will operate, but given the EU’s focus on Eastern Mediterranean and the Sahel, one might expect the first of such an intervention in Africa, with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and Syria with its so-called Kurdish Administration provide further possible areas of operation.

The establishment of the RDC is accompanied by the objective to be able to hold live military exercises – first time ever on the EU level – starting from 2023, to establish a military concept for air operations by that year, enhance and invest in military mobility (SC, 20). Additionally, maritime presences will be consolidated in the Mediterranean, where the EU sees over maritime disputes with Turkey considers its “maritime security” at stake (SC, 24), and at the Strait of Hormuz (SC, 19). Additionally, maritime exercises are planned in the Indo-Pacific by 2023.

3. Militarization

The Strategic Compass’ militarization efforts fall into two categories: The further strengthening of the armed forces and the military use of civilian resources.

“Spend more and better”, summarizes the SC the strengthening of the armed forces. As noted above shall national defense planning be embedded into the EU’s scenarios, and a wide range of joint projects in arms development is proposed:

In the land domain, the EU targets to develop further Soldier Systems and the Main Battle Tank. On the seas, the European Patrol Class Surface ship is the first step on a road that leads to high-end naval platforms including unmanned platforms for surface and underwater. In the air domain, UAVs, famous as Eurodrone, are planned as well as air defence systems. Space and cyberspace are further fields of defense development (SC, 32).

As mentioned above, are the member states called upon to fulfill their financial commitments to PESCO, and the potential of the European Defence Fund shall be exploited. The second aspect, military use of civilian resources comes into play here.

The Strategic Compass proposes to enable “access to private funding for the defence industry” and using the European Investment Bank. As additional incentive, a reduction of VAT in arms production and procurement is considered (SC, 33).

And lastly, civilian transport infrastructure shall adapt to dual-use and become able to “sustain short-notice large-scale movement” (SC, 20).

4. Domestic preparation

Every war has a domestic front, as the own society needs to be convinced of the military efforts to carry its own burden for conflict. The EU addresses the need its own society to its accelerated aggression with a so-called EU Hybrid Tool Box.

Within that box, the EU “needs to bolster our societal and economic resilience, protect critical infrastructure, as well as our democracies and EU and national electoral processes” (SC, 22, Eio.). This is the so-called home front, where all political actors are revised whether they comply with the given military intervention or conflict.

Part of that tool box is also press censorship. The Strategic Compass formulates as follows: “We will develop the EU tool box to address and counter foreign information manipulation and interference” (SC, 22, Eio).

In addition to the usual cyberspace measures, the EU also declares a new program to screen incoming Foreign Direct Investment under the criteria of security (SC, 38). Reducing strategic dependencies in technologies and value chains as well as improving armed forces’ ability to support civilian authorities in emergency situations are also part of domestic preparation (SC, 29).

In summary, the European Union proceeds with the militarization of its foreign policy. The measures planned in the Strategic Compass indicate its regional limitation. Still, the EU even takes preparations in the domestic front, showing it expects serious conflict.

The concept of strategic autonomy as much discussed of the EU becoming independent from the US is given very little attention. Instead, it is only hidden in details and side notes, with the EU preparing more to substituting the US in its region than competing with it.

Concerning the Strategic Compass’ implementation, much will depend on the ability of Brussels to impose its will on member states. Examples of its failure to achieve that are not hard to find – especially in the field of common security and defence policy.

[i] The European Union’s Coordşnated Annual Review on Defence CARD, takes – in a very diplomatic manner – on the problematic of EU member states providing resources to NATO instead of the EU. For its 2020 report see: https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/reports/card-2020-executive-summary-report.pdf

[ii] See https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8216/

Leave a Reply