By Adem Kılıç *

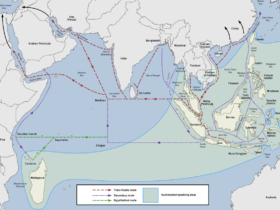

There are many problems between Türkiye and Greece on many issues, varying from the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean to the Greek expansion of territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles and the militarization of the Aegean Islands.

Among these problems, the crisis regarding the Dodecanese Islands has started to take more attention, due to Greece’s practices that do not recognize the international law, especially in the recently.

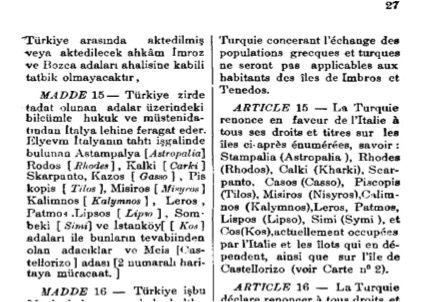

Unlike what the name suggests, the Dodecanese Islands (meaning “twelve islands”) do not consist of only 12 islands, but actually of 14 larger, and more than 20 smaller islands and islets. The 14 major islands are; Batnoz (Patmos), Lipsi, Ileriye (Leros), Kelemez (Kalymnos), Istankoy (Kos), Incirli (Nisyros), Istanbulya (Astypalaia), Ileki (Tilos), Herke (Chalki), Kerpe (Karpathos), Coban (Kasos), Sombeki (Symi), Rodos (Rhodes) and Meis (Kastellorizo).

In addition to these major islands, there are approximately 130 more islands, islets and rocks throughout the Sea of Islands (the Aegean Sea), which are defined in a “gray zone” or as “islands of undefined ownership”.

The Greek government currently clearly violates the treaties of international non-militarization by stationing troops at brigade and division levels and arms of varying numbers and sizes on a large portion of these islands.

The historical process

As a result of the process initiated in 1821 with the help of the Great Britain, Italy, France and Tsarist Russia, Greece gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire on April 24th 1830.

As Greece gained its independence, it has based its foreign policy almost completely on the “Megali Idea” ideology, and followed a path of expansion by constantly seizing lands from the Ottoman Empire.

Great Britain has ceded the Ionian Islands to Greece in 1864. Athens has since then been supported by the Western powers, has continued to make border corrections in its favor and expanded between 1881 and 1897 again with the support of Western powers.

Under these developments, Italy, one of the major powers of that time and especially in the second half of the 19th century, has extended the conflict all the way to the Sea of Islands, in order to cut off the Ottoman aid to Tripolitania region during the Italo-Turkish War (1912). After this war, Italy occupied these fourteen islands and all other small islets in the Sea of Islands, bringing a whole new dimension to the issue of dominance over the Sea of Islands.

In the Treaty of Ouchy, signed at the end of the war, it was decided to return the islands back to the Ottoman Empire.

Despite this agreement, the islands were not returned to the Ottoman Empire and remained in Italian possession after the outbreak of the Balkan Wars.

According to the Treaty of London signed on May 30th 1914, right after the Balkan Wars, the Western powers decided to cede all islands, including Meis (Kastellorizo), Bozcaada (Tenedos) and Gokceada (Imbros), to Greece on the condition that all the islands, including the Dodecanese Islands, would be completely demilitarized and disarmed. However immediately after the outbreak of World War I, the Dodecanese Islands stayed under the control of Italy.

And with the end of World War I, the Article 122 of the Treaty of Sevres demanded that the Ottoman Empire would renounce all its rights over the Dodecanese and Meis (Kastellorizo) in favor of Italy.

In the meantime, the Treaty of Bonin-Venizelos, which entered into force simultaneously with the Treaty of Sèvres, declared to leave all the islands except Rhodes and Meis to Greece.

The process that extends to this day has begun after these developments.

As a result of the defeat of Greece in Asia Minor, the Treaty of Sevres and the consequent Treaty of Bonin-Venizelos were nullified. Italy announced that it had cancelled the treaty and that the relevant islands were again under Italian protection on October 8th 1922. On the other hand, since the Turkish Republic did not ratify the Treaty of Sevres, the status of the islands remained to be debated on the Lausanne Peace Conference.

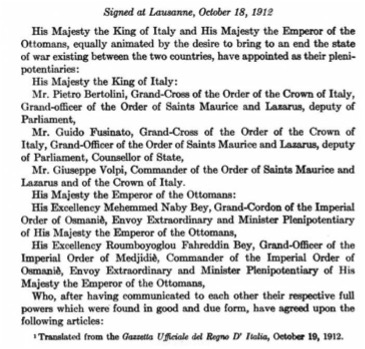

Thus, the Lausanne Peace Treaty of July 24th 1923 is the most important document regulating the current status of the islands.

Regarding the sovereign rights over the islands, Articles 12, 15 and 16 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty have the appropriate provisions. Article 12 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty determines the return of the Eastern Aegean islands, except for the islands of Gokceada (Imbros), Bozcaada (Tenedos) and Tavsan (Lagousos) Islands, to Greek rule, while Article 15 decided to leave the 13 islands and the islets connected to them around the Mentese region, to Italy. And in the Article 16, the Ottoman Empire was now recognized as the Republic of Türkiye in the treaty.

And Türkiye has accepted that it has renounced all rights and titles over the islands, other than those mentioned in the treaty, provided that it reserves the right to have a say in its future ownership.

However, those who thought that the process related to the islands had ended here would be mistaken.

Especially the islands would become a matter of debate, despite Türkiye’s policy of neutrality in the World War II. The Germans occupied these islands and Crete during World War II, which began in 1939 and ended in 1945. Then, Germany signed the Turkish-German Non-Aggression Pact, in order to secure the Turkish border right before attacking the Soviet Union.

Germany even offered to give these islands back to Türkiye in 1940, in order to prevent the Turkish-Soviet rapprochement during this time period. However, the Turkish President of the time period Ismet Inonu, who was also an influential figure in the Lausanne Treaty, rejected this offer on the grounds that “Türkiye does not seek to seize more lands from its neighbors, and also does not have sufficient resources to govern the islands”, and informed the Great Britain of this decision.

Ismet Inonu also rejected Stalin’s proposal to cede parts of the Dodecanese Islands, a portion of the Bulgarian lands, and a part of Northern Syria to Türkiye, by saying “we do not find this proposal to be genuine, and do not wish to be a part of that”.

Following all these developments, Türkiye issued a statement after a series of events such as the Soviet occupation of Romania and Bulgaria in early-1944, and the British occupation of Greece in the last months of that same year. It informed Greece that it had no claims on the Dodecanese Islands and wished to establish a close cooperation with Greece by the end of the war.

Upon the surrender of Germany in 1945, German forces stationed on the Dodecanese were withdrawn from the islands. And after their withdrawal, British forces settled on all of these islands, and a de facto British rule was established. Following this development, Greece demanded that the Dodecanese Islands, and especially Rhodes, to be ceded immediately.

Following this demand from Greece, the Dodecanese issue was discussed in the Peace Council held in London in 1945. Britain confirmed the de facto control of the islands, and stated that Greece’s demand was seen quite positive. Britain announced that they wanted to transfer these islands to Greece. The United States and France also supported this decision.

In light of these developments, Dodecanese Islands were included in Article 12 of the final draft of the Paris Peace Treaty 1946, and the Dodecanese Islands were transferred to Greece on the condition that they were to be demilitarized and disarmed.

An evaluation of this historical process

Throughout the last decades of the Ottoman Empire, a large part of the Aegean Islands was ceded to Greece as a part of the agreements made after the Balkan Wars of 1913 and the World War I, while provisions were made that all the islands closer to the coasts of Anatolia should be kept demilitarized.

There are 6 supervisor states that are authorized by both the London and Paris agreements: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, France, Italy and Russian Empire. All have made provisions that the aforementioned islands “cannot be fortified” or “cannot be used for military purposes”.

Under the headline of “Dodecanese Islands”, the Paris Treaty mentions these 14 islands including the Meis (Kastellorizo) Island, and dictates that these islands, which were ceded from Italy to Greece, shall be “demilitarized and will remain in that status”.

In Article 12 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty, one of the peace treaties signed after the First World War, this decision taken by 6 states was approved exactly.

The Article 13 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty contains the following dictate;

“No naval base and no fortification will be established in the said islands. (…) The Greek military forces in the said islands will be limited to the normal contingent called up for military service, which can be trained on the spot, as well as to a force of gendarmerie and police in proportion to the force of gendarmerie and police existing in the whole of the Greek territory.”

The Greek arguments

Greece, which started re-militarizing some of these islands in the early 1950s, still tried to keep these actions secret until the 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation. And immediately after the operation, they have begun to put forward some legal arguments to justify this re-armament.

Greek administration is currently presenting the following four main arguments.

The first of these arguments is the claim that the Montreux Convention abolishes the provisions regarding the demilitarization status of the islands of Limnos and Semadirek (Samothrace), which are located right across the Dardanelles.

Secondly, Greece makes the claim that necessary measures should be taken to prevent the expansion of Türkiye’s territorial waters in the Sea of Islands, after the Cyprus Peace Operation and formation of Turkish Aegean Army (4. Army).

Third argument is the claim that the provisions on the demilitarization of these islands have been abolished within the framework of the “current conditions showing that Türkiye is an aggressor state”, in reference to the Turkish Grand National Assembly’s decision in 1995 that “Greece’s decision to extend its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles, is a casus belli”.

And lastly, Greece claims that the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947 is a treaty that constitutes a “res inter alios acta”, that is, a treaty that gives rights and obligations only to its signatories, and that as a non-signatory state to this treaty, Türkiye has no right to object to Greece’s re-armament of these islands.

Another claim of Greece over the same region concerns the airspace related to these developments over the islands. Against the objections of Türkiye, Greece reacts to the fact that the territorial waters of these Greek islands stretch 6 nautical miles but the airspace stretches to 10 nautical miles, and claims that this paradoxical practice was introduced in 1931.

Greece, which extended both its territorial waters and its airspace by presidential decree, up to 10 nautical miles in September 1931, decided to keep its territorial waters at 6 nautical miles in order to facilitate the passage of ships throughout the Sea of Islands. However, it notified to Türkiye that the airspace was kept at 10 nautical miles as well as to the International Commission for Air Navigation (ICAN), which was renamed to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) later in 1949.

They claim that International Maritime-Aviation maps published in 1955 also showed Greek airspace at 10 nautical miles and suggest that this can even be seen on the Turkish nautical-aviation maps of that time.

To reinforce this argument, Greece claims that the Turkish military flights stayed away from these nautical 10 miles of the Greek airspace between 1931 until the 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation. But since 1975, it considers military flights into the remaining 4 nautical miles after the initial 6 nautical miles as a violation of Greek airspace.

It is necessary to note that neither the aforementioned airspace claim nor the other claims doe not reflect the reality.

In fact, according to the official records of NATO, of which Greece is a member state, its airspace is accepted as 6 nautical miles away from the island, and not 10. And more interestingly, Greece still acts according to this rule in its NATO exercises. In the light of these data, the US and NATO seem to accept the airspace of the Greek islands as 6 nautical miles away from the islands during their exercises held across the Sea of Islands.

In other words, this argument of Greece stands out as an invalid argument in terms of international agreements or the international law.

The Grey Zones in the Sea of Islands

The issue of grey zones also draws attention as a topic that has been added to the disputes between Türkiye and Greece in the Sea of Islands, especially in the recent years.

The first crisis broke out in 1996 over the Kardak (Imia) rocks, which brought Türkiye and Greece to the brink of a war. This has caused the two countries to turn their attention to the smaller islands, islets and rocks throughout the Sea of Islands, which were labeled with “undefined ownership”.

Referring to Article 12 of the 1923 Lausanne treaty, Greece defends the argument that “Türkiye only has rights to the islands, islets and rocks within its 3-nautical miles territorial waters.”

Some treaties and the international law refute this argument from Greece, because according to Article 15 of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty and Article 15 of the 1947 Greco-Italian Treaty, Greece only has rights to the islands that are named in the treaty, transferred by Italy.

And there is no agreement that determines the ownership of the approximately 130 smaller islands, islets and rocks, that are described as “grey zones” and whose “ownership is undefined”.

The Turkish arguments

Türkiye first sent a diplomatic note to Greece in 1964 upon the start of arming the islands, stating that the re-armament activities detected in islands of Rodos (Rhodes) and Istankoy (Kos) were contradicting international treaties. Türkiye demanded that these armament efforts should be stopped.

In response to this diplomatic note, Greece denied the claims, stating that it still complied with the treaties and did not carry out any militarization activities on the islands in question.

Türkiye took a step further in this regard in 1969. Ankara has revealed information about the armament of the island of Limni (Limnos) and has given another diplomatic note to Greece. Greece again denied the allegations, claimed that it respects international treaties and that the activities are reserved only for civil aviation purposes.

In both diplomatic notes, Türkiye came forward with the legal arguments mentioned in the international agreements and acted within international law by referring to both Article 12 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty, and Article 14 of the Paris Peace Treaty.

Türkiye’s recent official statements and its approach, suggest that the Greek militarization actions constitute a “material breach” for the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne, over the islands. In this case, Türkiye declares that it has the right to claim that the provisions of the Lausanne Peace Treaty on sovereignty over the islands have come to an end.

Conclusions

The arguments of Türkiye and Greece should first be evaluated in the context of international law.

First of all, the Greek approach of “Türkiye’s activities threaten the security of the islands” does not indicate that Greece has obtained the right to re-arm the islands in the context of the international law.

This situation is incompatible with the definition of “right to self-defense” in the international law. In the international law, the right to self-defense is defined as “a right defined as a result of an attack”. In this context, it is impossible for Greece to use Türkiye’s routine activities within its continental shelf as a “right of self-defense” and to use this basis to militarize the islands.

On the other hand, the fact that Türkiye is not a signatory to the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty does not conclude that Greece can violate the disarmament provisions, as Greece claims. Even though these provisions are already present in more than a single agreement, and the international law also uses previous practices as a basis, in the case where there is no agreement between two parties. Both of these situations are clearly in Türkiye’s favor.

It should also be noted that the airspace claims does not reflect reality like any other claims.

According to the official records of NATO, of which Greece is a member, its airspace is not defined as 10 nautical miles, but 6 nautical miles. And as a matter of fact, Greece still acts based on this rule during its NATO exercises. In the light of these official data, the US and NATO accept the airspaces of the Greek islands to be 6 nautical miles, during their exercises held across the Sea of Islands.

In other words, this argument of Greece stands out as an invalid argument in terms of international agreements and the international law.

Lastly it is obvious that these islands may pose a direct threat to Türkiye’s national security both in a possible conflict between the two countries, or in case of a full-fledged war, due to their proximities to Türkiye. The Article 13 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty clearly relates the disarmament provision to “keeping the peace”, on the issue of disarmament of the islands. Greece’s activities certainly violate this principle.

All these findings show that the violation of the rules on disarmament by Greece may give Türkiye the rights to terminate the provisions of the Lausanne Peace Treaty, that regulate sovereignty over the islands. This would give Türkiye the right to demand a renegotiation for the sovereignty over the islands with Greece.

* Political Scientist / Author

Leave a Reply