By Orçun Göktürk

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was presented by Chinese President Xi Jinping during his trip to Kazakhstan in 2013, was the first target of Brahma Challaney’s “Debt Trap Diplomacy” black propaganda in 2017[1]. Since then, Western countries have adhered to the phrase and begun focusing on the leading BRI in the newly reorganised international system. This disinformation campaign claims that China is putting countries in unsustainable debt through the BRI, increasing their dependence on China, and increasing China’s political influence over them. This claim mainly targeted Chinese investments in Sri Lanka and Malaysia as the countries where China had implemented a “debt trap.”

However, recent developments in Sri Lanka provided an “opportunity” for Western countries, especially the United States of America (USA), to spread the myth that “China owes Sri Lanka debt, the people revolted.” This article will discuss the false argument, BRI’s “debt trap”, as well as the problem of external debt facing Sri Lankan economy.

The problem of Sri Lanka’s external debt

The small but strategically significant nation of Sri Lanka, located on the Indian Ocean, is one of the countries on the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” of the Belt and Road Initiative. Since the end of the civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka’s economy has grown quickly, but there have also been increases in its external debt and economic risks. The ultimate cause of Sri Lanka’s external debt problem is the issue of development and its derivative, how to ensure the country’s post-civil war economic recovery and growth.

First debt from the World Bank…

In 1954, Sri Lanka received its first foreign debt from the World Bank in the amount of 130 million Sri Lankan Rupees to meet its domestic financing needs[2]. Following this, Sri Lanka continued taking additional loans from various Western governments and financial institutions. The total amount of Sri Lanka’s external debt in 1983 was 46 billion rupees. Since then, the nation has suffered a dramatic foreign debt crisis and has added new foreign debt to its existing foreign debt to pay off its current debt. Contrary to popular belief, the majority of it was not from China, but from Western countries and financial institutions!

When Mahinda Rajapaksa took the power in 2005, Sri Lanka’s debt to GDP ratio was 91%. In 2009, the country’s economy experienced sustainable growth, the value of the rupee stabilized, domestic and foreign investments increased, interest rates decreased, fiscal deficits were reduced, and inflation was under control after a 40-year civil war with Rajapaksa. Sri Lanka’s debt to GDP ratio was only 71% in January 2015 (a 20 percentage point drop over 10 years)[3].

However, under Maithripala Sirisena’s administration, which began in 2015, the country’s debt once again rose to unmanageable levels. The debt-to-GDP ratio of Sri Lanka rose to 81 percent in 2017, according to the nation’s former central bank governor.

Even though Sri Lanka’s external debt has continued to rise since 2011, the risk related to debt repayment was anticipated to be manageable based on economic indicators. The main causes of Sri Lanka’s external debt issue are imbalances in domestic production, international trade, financial spending, and debt management. China has landed a hand and, using the concept of “mutual benefits,” the Chinese and Sri Lankan governments have signed numerous trade agreements as part of the BRI.

The debt ratio, one of the three important indicators used to analyse a nation’s external debt load, expresses the ratio of that year’s external debt to GDP. The accepted safety line for the debt-to-income ratio is 25%. Figure 1-1 clearly shows that Sri Lanka has a debt ratio of at least 50%, which is double the accepted guarantee rate of 25%. It should be emphasized once again that the main factor contributing to the exceedance of the guarantee ratio is the debt to Western institutions.

Figure 1.1 Sri Lanka’s External Debt Service and Debt Ratio from 2009 to 2016:

| Year | Debt Service Ratio | Debt Ratio | ||

| 2009 | 22. 4% | 233% | ||

| 2010 | 16. 7% | 223. 7% | ||

| 2011 | 12. 7% | 211. 5% | ||

| 2012 | 19. 7% | 273. 3% | ||

| 2013 | 26. 8% | 264. 6% | ||

| 2014 | 20. 8% | 256. 4% | ||

| 2015 | 27. 3% | 264. 6% | ||

| 2016 | 25. 0% | 267% | ||

| 2017 | 23. 85% | 271% |

Source: Annual Economic Outlook Report of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2017)

The helping hand of the Belt and Road Initiative

In less than a decade, between 2009 and 2017, the country’s total external debt more than double, rising from $20.913 billion to $51.824 billion, according to the Sri Lankan Central Bank.

China’s investments have begun to ease the country’s chronic debt crisis. By the end of 2015, economic activities made up the majority (50.5%) of Chinese loans, followed by agricultural development (5.11%), industrial and construction projects (27.49%), and the service sector (13.9%), and other economic activities (4.24%). Social services took the second place with 10.31 %, followed by goods, food, and other activities with 2.02 %.

Sri Lanka received $12.1 billion from China as infrastructure investment between 2006 and 2019. Major infrastructure projects, including ports, highways, and irrigation systems, were funded by China under the BRI. The crucial difference between BRI Investments and capital inflow from Western nations is their positive effects on significant infrastructure projects and employment growth, which demonstrate special attention.

Largest external debt is to Western markets!

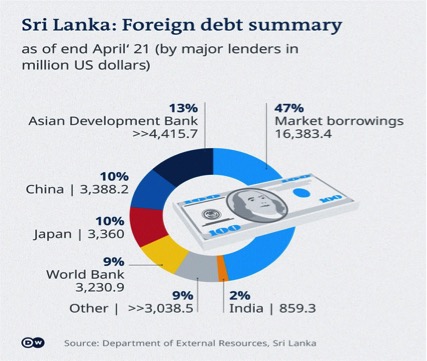

Sri Lanka’s external debt can be divided basically into three categories: Government external debt (Sri Lanka’s main lenders are China and Japan); international and regional multilateral financial institutions, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF); lastly, the international financial market (mostly to Western countries or institutions).

Sri Lanka’s international debt problems are not caused by China but by Western markets, where it received the majority of its debts (See Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. Summary of Sri Lanka’s external debt:

Source: Deutsche Welle

The current problem with Sri Lanka’s external debt began in the 1960s and has only gotten worse. By keep borrowing new foreign debts to cover existing debts, the country goes round in circles”. Due to a protracted civil war, political unrest, social conflicts, and the failure to take advantage of the economic ties between East and Southeast Asia, development opportunities were lost as the country’s industrialization failed. Sri Lanka is entirely dependent on imports because of its fragile industrial structure at the moment. Due to its small production structure, Sri Lanka principally exports primary goods. Since more than 85% of Sri Lanka’s external debt has a repayment period of more than 15 years, the burden of debt is primarily the result of years of accumulation.

As a result of the pandemic, the majority of Western-based foreign capital stock in Sri Lanka began to leave the country, and the value of the local currency relative to the US dollar started to fall to record lows.

Who is to blame for the debt trap?

The majority of Sri Lanka’s total external debt—nearly 60 percent—is owed to Western capital markets. Even though the percentage of loans from China rose from 2% in 2008 to 9% in 2017, their value as a percentage of the total share is still low. The information disproves the argument that China has set up a “debt trap” in Sri Lanka. Because Western financial institutions, the USA, Europe and Japan are the largest holders of the country’s foreign debt.

As of 2017, Sri Lanka owed a total of USD 51,824 billion to foreign creditors, with loans from China accounting for approximately 5.5 billion USD, or 10.6 percent, of total amount. Moreover, 61.5% of China’s loans are long-term, concessional loans, which do not make up the majority of Sri Lanka’s external debt.[4]

Additionally, the majority of Sri Lankans (60 %), according to a 2019 report by a Colombo-based survey company, think that China supports Sri Lanka’s national interests. There is no doubt that Sri Lankan state officials and the general public do not harbour any misgivings about BRI and Chinese investments and disapprove of the “debt trap diplomacy” argument.

The US wants to destruct, BRI is constructive

Countries like the United States, Europe, Japan, and India, as well as international organisations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, imposed economic sanctions on Sri Lanka up until its civil war came to an end in 2009. The country was in danger of division during this civil war, which began in the late 1980s and continued until the 2010s, and it is estimated that more than 40,000 civilians died. The most critical external cause of the country’s economic crisis is the Western embargo, which was cruelly imposed on it during this process.

In conclusion, the Sri Lanka issue is not related to China but rather is a result of US imperialism when we consider the bloody history of the USA and the CIA with debts, occupations, the overthrow of governments, and assassinations.

[1] Chellaney, Brahma. China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahma-chellaney-2017-01

[2] Presbıtero A F. Total public debt and growth in developing countries. The European Journal of Development Research, 2012, 24(4): 606–626

[3] Tang Pengqi. The Current Situation, Impact And Countermeasures Of The Debt Crisis Since Sri Lanka Kasrissena Took Office. South Asia Research Quarterly, 2018, April.

[4] http://world.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0705/c1002-30129686.html

Leave a Reply