Following Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine, a debate lived up again on the role of force and violence in history – especially concerning the history of Russia itself. United Woeld International author has given a lengthy interview to Emrah Maraşo, editor-in-chief of Turkish monthly magazine Bilim ve Ütopya (Science and Utopia).

The interview was published first in Turkish. UWI presents it in chapters to our readers.

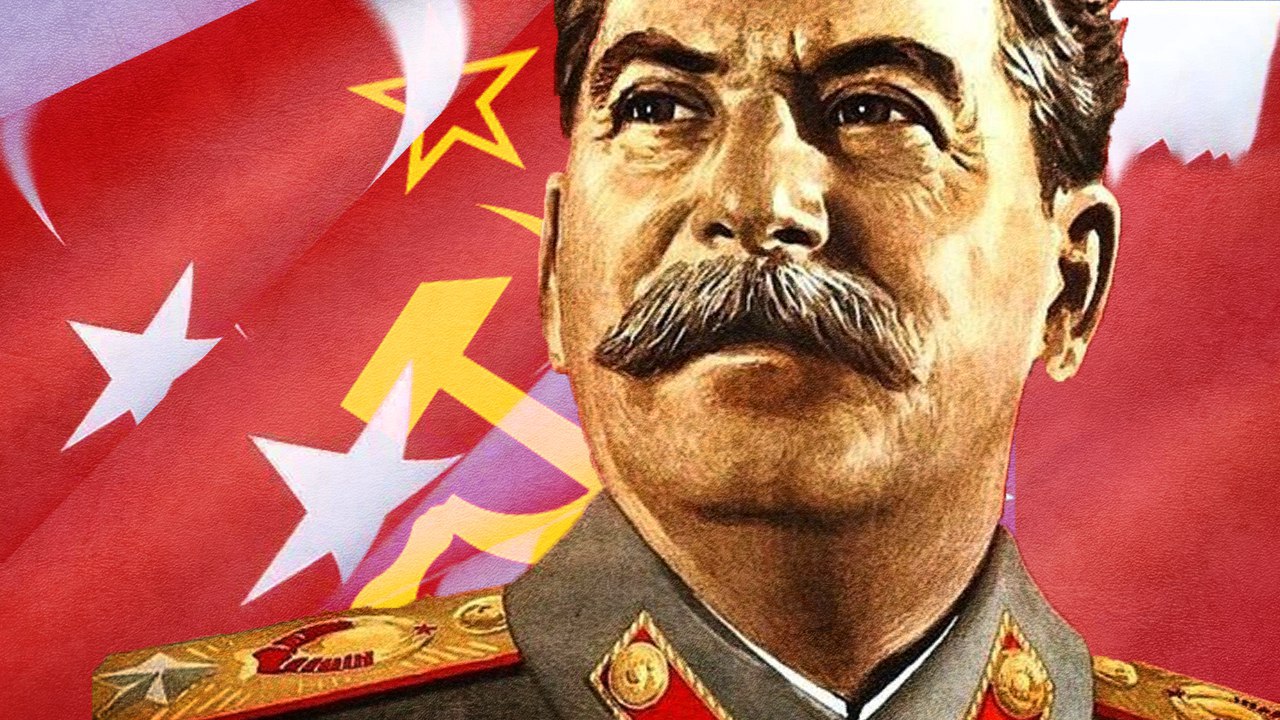

What happened in the period after Stalin? Did the perspective you just mentioned about Ivan change step by step? With his famous speech at the 1956 party congress, Khrushchev began to follow a line “condemning” Stalin and revealing the power of revisionism within the party. How did this reflect on culture and art?

The state and the use of violence

The first thing to say is this: Every state uses violence. Violence is at the core of the state. It has military, police, intelligence service, and prison. In terms of the use of violence, no two states are different from each other. Of course, this is true for real states, not for banana republics. When we compare the Stalin and Khrushchev periods (the revisionist period), we find that there is the use of violence in both periods, but the difference lies in where the violence is aimed and for what purposes.

Violence to what ends?

Under Khrushchev, all the important figures of the Stalin era were purged one by one, people who had been top government officials and World War II heroes were imprisoned for twenty years or so. Under Khrushchev-Brezhnev, authoritarianism persists. Whereas under Stalin violence was used as an apparatus to protect the country’s prosperity against foreign powers and to consolidate the rule of the working class, under Khrushchev-Brezhnev to consolidate the power of the capitalist travellers and the privileged class within the party. And in terms of foreign policy, for social-imperialist ends. Instead of strengthening the Red Army against German fascism during the Stalin era, the Khrushchev-Brezhnev eras, just like the US, sought to exploit other countries and turn them into satellites. We can list incidents from the Prague Spring to the invasion of Afghanistan. In short, violence is a fact for both periods.

‘Peaceful coexistence’

After Stalin’s death, the CPSU adopted a policy of what it named “peaceful coexistence”. Did this policy play a role in the collapse of the Soviet Union and in fueling imperialist violence?

Lenin and Stalin also practiced the politics of “peaceful coexistence”, and it is the correct policy. But just as you can implement this policy to curb imperialist aggression, so can you use it to justify or compromise with it. Khrushchev’s policy of peaceful coexistence at the 20th congress is a degeneration of Lenin’s. In this new state, the Soviets began to see the struggles and armed uprisings of the oppressed countries striving for freedom as breaches of the peace. These countries were warmongers in the eyes of Khrushchev and Brezhnev. Unless they revolted, they would “live in peace”. What Stalin was trying to show, in all the meetings like that in Potsdam starting with the Tehran Conference, was that people from different ideologies and sections in society could coexist peacefully along with the politics of a united front against fascism.

This is what China is seeking to accomplish today. At the time, the Chinese leadership saw the new Soviet policy as a policy aligned with the imperialist bloc and as a plot against the liberated countries. China argued that Soviet policy has turned into the suppression of national liberation movements under the pretext of preventing war.

Apart from this, we should point to the importance of dealing with the contradictions within the people, between the people and the state, within and between the oppressed and developing countries.

At which point did Mao differ?

A position centered on the praise of violence is not correct. Here was where Mao differed: He took a clear stand against revisionism, but he also pointed out the mistakes in the Stalin era. Mao criticized the Soviets’ deviation from dialectical materialism and objective reality, the idea that communism had been achieved, the 1936 constitution, the move away from the mass line, and the attempts to push the revolution forward by relying merely on the state apparatus at certain periods.

In the age of imperialism, violence is important for oppressed and developing countries to keep the internal front strong and to stand firm against foreign powers. Nevertheless, this should not lead to the misuse of violence in dealing with the contradictions within the people. It is necessary to acknowledge that solving problems solely through state authority and apparatus is not possible. It is a mistake to disregard the two-line struggle. This applies to both the party and the country. We should also note Mao’s criticism that the principle of democratic centralism was not completely implemented during Stalin’s rule.

At this point, the following came to my mind: Marx, in the section about the origins of violence in Russia in his book on secret diplomacy in the 19th century, mentions Mongol rule as a crucial factor. Some Eurocentric explanations can also be based on things like those: “The eastern countries have not experienced democracy in the sense that Western Europe has. Therefore, violence is inherent in their political culture and daily lives”. What would you say about this?

Actually we have already discussed this issue at the very beginning. We can elaborate more on this Orientalist point of view.

The West adversary to strong armed forces in the East

I apologize that I am interrupting. Marx needs to be kept separate from the standard Orientalist point of view. Marx too occasionally makes Orientalist remarks. We have to admit that, but especially in the final period of his life, he turns his gaze to the East -the uprising in Ireland, the revolutionary movement in Russia, etc.

Imperialism and colonialism do not want to be opposed by violence. This is quite normal. If you are going to conquer, exploit or occupy a territory, of course you don’t want Ivan the Terrible or Stalin against you. If I were Hitler, I would not like to see Stalin in my way. If I were Biden, I don’t want to face Putin, instead, Gorbachev, Turgut Özal or Tansu Çiller. One does not want large, strong armies and commanders like Ataturk on the opposite front.

Barbarians and savages…

With discourses such as “these are barbarians, savages, they have weapons of mass destruction, they committed genocide on Armenians”, etc., imperialist violence not only tries to disguise its own violence but also wears down the armed forces of targeted countries politically and morally. In this respect, the Orientalist perspective is always the case. This is due to the very fact that they want weak and impotent people as their opponents.

When the West was encouraging the paradigm of civil society in Türkiye, it was strengthening its military and state apparatus at the fastest pace. For example, the invasion of Iraq was the epitome of violence.

“It is quite normal to see blood and war in Africa and Asia, but not in Europe. These things are very alien to Europe.” This is all part of the struggle you just mentioned on a different, ideological, plane.

Of course yes. All the world wars were born out of Europe’s greed for profit. Apart from the world wars, there are big wars within Europe itself, like the Thirty Years’ War.

This is how the West perceives it: The violence it uses is not violence, but “bringing civilization and democracy”. There are cannibals and barbarians who object to this “democracy”. The West is obliged to fire some bullets in response. Resistance amounts to barbarism and savagery and what the West is doing is the transfer of civilization and culture…

Leave a Reply