by Dure Akram reporting for UWI from Lahore, Pakistan

This is the first part of the interview focused on domestic Pakistani politics. Tomorrow follows the second part with Imran Khan’s views on foreign policy and regional relations – UWI.

Revolutionaries come in all shapes and forms and while former Prime Minister Imran Khan may not look like one, his energetic brushes with the status quo suggest otherwise.

Panicked murmurs of something along the tune of what transpired in the premises of Islamabad High Court on Tuesday (when he was due to appear in a case of corruption allegations) had been running through the country since the night before.

A day earlier, he had sat down with United World International and talked about the “people who want (him) killed.”

“I have very powerful enemies, and all of them are scared of me coming into power,” a very straightforward Mr. Khan noted it just like it was.

Not a believer in holding any punches, he dauntlessly called one of the heads of the local intelligence agency, General Faisal Naseer, allegedly responsible for “not one but two assassination attempts on me.”

“It’s a risk every time I step outside my house”

“It’s a risk every time I step outside my house,” he had prophesied in an eerie manner, “considering their access to all the coercive power and information.”

His heated diatribe against the perpetrators of an assassination attempt on him had, nevertheless, resulted in a rather hard-hitting rebuttal from the public relations wing of the Pakistan Army. In a statement, the director-general had rebuked him for “hurling baseless allegations” against a senior military officer currently serving in the armed forces. Legal action could also be pursued, he warned.

That the president of his party and a staunch ally, ex-chief minister of Punjab Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi, admitted to pulling the brakes on the registration of the police investigation against the much-talked-about attack on a rally held last year further thickens the plot. Why is the opposition determined to fuel a narrative that reeks of divisiveness when one of their own was not interested in pursuing the complaint, many wonder? Considering the unwillingness of Mr. Khan to put forward any concrete evidence against the accused, some in his inner circle, including a key appointee, Sardar Tanveer Ilyas, have also decided to distance themselves from his allegations.

Visuals making rounds on social media show him composed amid shattered window panes as heavily-armed Rangers step towards him. There are reports of him being dragged across the courtyard. His counsel narrates hits on the injured leg as a sea of uniformed men struck the chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), a leading political party.

“All surveys show the PTI is ahead of other parties”

Moving fingers over charcoal prayer beads wrapped carelessly around his left wrist, his beady eyes intent on something far away, Mr. Khan believed in the strength of millions his party pulled. “All the surveys show that the PTI is way ahead of other parties.” His predictions are spot-on, as according to Gallup Pakistan, the ex-premier was overwhelmingly “positively rated” by 61 per cent of Pakistanis. Most of the by-polls held after he was ousted in a no-confidence move last year have been a clean sweep for the PTI. “This is what they are afraid of!” he exclaimed.

The unprecedented cricket icon is no stranger to popularity. Having an illustrious career in international cricket, his historic triumph in the 1992 World Cup rubberstamped him as “the finest cricketer to come from Pakistan.” The charismatic halo continues to this day as people herald him as a true messiah.

But when asked whether, at the height of his fame, he had considered entering politics, he laughed it off. “There is a very clear verse in the Quran. You make one plan and Allah makes another plan. But once I decide to do something, I never fear the consequences.”

“Big mafias have to loose”

“I will do whatever it takes to complete my mission even when it comes at the cost of my life,” he reaffirmed. Known for coining nicknames for his political rivals, he once again mentioned how the “big mafias” had a lot to lose and, therefore, “the stakes were much, much higher.”

At the center of the biggest political storm Pakistan has ever seen, Mr. Khan acknowledged that his life was in danger but continued, “The fear of death should never deter you from your objective, which is the rule of law and justice of Pakistan.”

However, Khan, too, knows that when given a chance, he had failed to fulfill all he had promised during the high-voltage campaign. The justification for their own lackluster performance remains the same as before: weak standing in the executive. Despite a successful election, Imran Khan’s Ministry was formed by forging coalitions with a wide array of partners. “A government needs strength to conduct reforms.”

Strong government needed for reforms

“Pakistan needs reforms in almost every sphere, but most of all in establishing the rule of law”, he maintained.

He called his weak government the biggest obstacle and went on to call out this dependency, as engineered by the Chief of Army Staff of Pakistan, General (R) Qamar Javed Bajwa. “General Bajwa made sure we were not strong enough,” he revealed.

“Between controlling the election commission, the accountability watchdog agency (National Accountability Bureau), and media and hammering out alliances with the two political families (Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and Pakistan Peoples Party), he ensured we were weak and would not implement any reform.”

Mr. Khan maintains that Mr. Bajwa played a phenomenal role in obstructing all reforms, the most important of which was “bringing rule of law” because of his influence on the accountability watchdog. “He would make sure the powerful crooks were not convicted,” the former Prime Minister claimed.

When asked about his plans for the future, he emphasized:

“Given the current economic crisis, there would be no point in forming a lame duck government, one without a strong majority or that depends on allies.” He even went on to proclaim that had he known the reality back in 2018, he would have never accepted the government and instantly gone for reelection.

Cautiously smirking at the oft-used phenomenon used to describe the power-sharing formula with the military leadership, Mr. Khan noted that he, too, had once believed they all stood on “one page.” Nevertheless, this union was short-lived as cracks soon appeared in the rosy picture.

Rule of law as the begin of a civilized society

Today, he prioritizes establishing the rule of law as “a beginning of a civilized society for prosperity, democracy and freedom, all follow afterwards.”

Determined to not continue with the “might is right” mantra, he regretted how Pakistan has never had the rule of law.

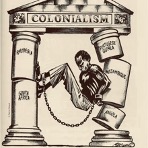

“The reason why Pakistan is becoming a failed state is our law of the jungle,” he remarked when acknowledging how it had always been under the control of military dictators. If not for martial law, the country was said to be at the mercy of “these family mafias (who) think they are above the law” no matter how many “crimes they commit.”

The writer tweets as @dureakram.

Leave a Reply