By Michael Roberts *

Over the next few posts, I aim to review a number of books published in the last year on key aspects of Marxist economic theory. I start with dependency theory.

Dependency theory emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a critique of ‘modernisation’ theory, which argued that poor countries could develop by following the same path as wealthy countries. Dependency theorists argued that this was not possible because poor countries are systematically exploited by wealthy countries. The theory was developed mainly in Latin America, when the so-called Golden Age of booming capitalist development after WW2 in the major advanced capitalist economies came to an end.

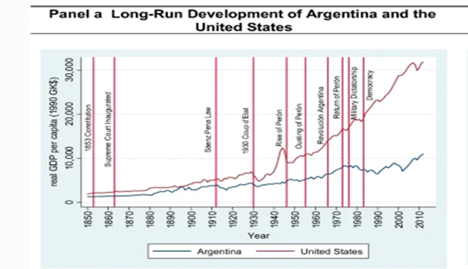

It seemed that economic development as in the ‘West’ did not apply to economies in South America, the Middle East or Africa. In 1945, Latin American countries like Argentina and Brazil had per capita incomes not so far behind that of the weaker capitalist economies of Southern Europe, and it was expected that under governments that looked to follow the industrial economies of the North, Latin America would prosper. That hope evaporated in the downturn in profitability and investment that ensued in the late 1960s and through the rest of the 20th century.

In his book, now published in English, Claudio Katz, a professor at the University of Buenos Aires and author of many books on economics and Latin American society, provides us with a comprehensive account of dependency theory as expounded mainly in Latin America over the last 50 years. It won the Libertador prize for Critical Thought in 2018.

I think we can start to consider dependency theory from a brief phrase that Marx wrote in his 1867 preface to Volume one of Capital. He wrote: “The country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future.” Marx was writing when Britain was at the pinnacle of its economic power and industrial might. Capital was an analysis of such a capitalist economy. And Marx thought capitalism would spread globally so that other rival capitalist powers would emerge – and he was right. Germany, France and, above all, the US caught up with Britain (in its own ‘image’) by the end of the 19th century.

But we now know that it would only be a small group of industrial and commercial capitalist economies that achieved Marx’s prediction. Those powers were then able through military, financial and technological prowess to block the progress of capitalists and their workers in most of the rest of the world. Lenin wrote in 1915 that there were just a handful of countries that controlled the world’s technology, finance and resources. One hundred years later, those ‘imperialist’ economies are much the same and broadly still dominant. And thus we can talk of a dominant imperialist bloc and a ‘dependent’ rest of the world.

But ‘dependency’ can take different meanings and Katz shows us that it does with his discussion of the variants within the dependency school. Dependency theorists identify two main groups of countries in the global economic system: the core and the periphery. The core countries are wealthy countries that control the global economy. The periphery countries are poor countries that are dependent on the core countries for trade, investment and technology. Indeed, the word ‘periphery’ seems better to me than ‘dependent’. The latter could imply that the capitalist class in the periphery plays no independent role in exploiting its own working class, and exploitation is totally the result of imperialist domination and foreign companies.

Where dependency theory plays a positive explanatory role is in the idea that resources flow from a “periphery” of poor and underdeveloped states to a “core” of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. The theory rejects the mainstream theory of ‘development economics’ upon which the international institutions of the United Nations (UNCTAD – ‘trade and development’), the World Bank and IMF stand, that all societies progress through similar stages of development and that today’s underdeveloped areas are thus in a similar situation to that of today’s developed areas at some time in the past. Therefore, the task of helping the underdeveloped areas ‘out of poverty’ is to accelerate them along this supposed common path of capitalist development, by various means such as investment, technology transfers, and closer integration into the world market. The periphery is thus described as ‘emerging’ or ‘developing’ economies.

It would be wrong to think that Marx adopted ‘development economics’ in that sense as in the quote from Capital. Then he was referring to the immediate industrial capitalist economies of his day. In his later writings, he emphasized how the most populated countries like India, Russia and China were exploited and eventually suppressed in their ability to join the leading industrial nations.

Katz concentrates his account of dependency theory on its Marxist variant, rather than the mainstream one that argues dependency can be overcome by national policies of Keynesian-type state spending, import substitution for foreign goods and financial regulation. This variant has shown to have failed in practice in taking countries like Argentina or Brazil into the top tier of capitalist economies. Instead, Marxist dependency theory argues that these countries will remain ‘dependent’ because of the huge extraction of value from labor in their economies to the imperialist bloc through trade, finance and technology.

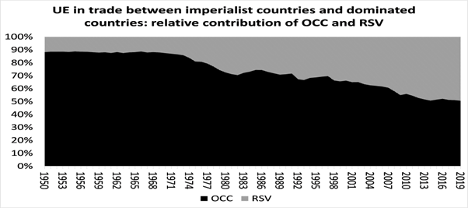

‘Unequal exchange’ in international trade is a fundamental component of Marx’s theory of value. However, within dependency theory, differences arise on the nature of that unequal exchange: is it due to wage differences or technologically driven productivity differences? Do the imperialist countries through their multi-nationals gain surplus profits from the cheap labour of the peripheral countries or from their superior technology and lower unit costs in international trade?

Katz reckons that the most prominent of Latin American Marxist dependency theorists, Ruy Mauro Marini “had greater affinities with those who ascribed unequal exchange to differences in productivities rather than wages.” This maintained that the wage gaps were explained by disparities in the development of the productive forces rather than vice versa. “The wage is a result rather than a determinant of accumulation, arguing that wage levels in each country depend on productivity, cycles, capital stock, and the intensity of the class struggle.”

If this was Marini’s position, then I agree. My own empirical study jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi on modern imperialism finds that the transfer of value from the periphery to the core economies through unequal exchange in trade is mainly due to productivity differences and technological superiority (OCC in the graph below), and only to a lesser extent due to higher rates of exploitation in the periphery. And it is not due to lower wages per se.

However, Marini did propose the concept of super-exploitation, namely where wages in the periphery fall below the value of labour power or below the average international wage. According to Katz, “it was the central thesis of dependency theory inspired by Marini.” But Katz argues that ‘super exploitation’ cannot be the main determinant of value transfer between rich and poor countries. “It dilutes the logic of surplus value” and it suggests a Proudhonian concept of theft rather than the “objective logic of accumulation”. As Katz points out, super exploitation also exists in neoliberal imperialist economies with ‘precarious employment’ and zero-hours contracts etc.

In my view, the point is that the value transfer to the imperialist North takes place because of their superior technology and labour productivity. That enables the imperialist North to sell its goods in world markets at costs below the international average. The capitalists of the periphery try to compensate for their lower technical level and productivity by driving the wages of their workers down. So the higher rate of exploitation in the South, whether by super-exploitation or not, is a reaction to the failure to compete against the North.

Was monopoly power the main cause of the dominance of imperialist companies? Some dependency theorists claim so. However, Katz reckons that was not the case with Marini. “Marini was always closer to the Marxist thinkers like Mandel who highlighted this dynamic of differentiated competition among monopolies. He maintained greater distance from theorists like Sweezy who stressed the unrestrained ability of large firms to manage prices.” But Marini did not go so far as Shaikh who Katz argues denies “the clear existence of gigantic corporations that obtain extraordinary profits in certain markets at the expense of smaller companies.”

Katz reckons that Marini had what I would call an eclectic understanding of Marx’s value theory. “He belonged to a tradition in Marxist economics that disagreed with the approaches centered exclusively on the analysis of value in the sphere of production. That approach quantifies value only in the initial phase of surplus value creation, insistently pointing to the weight Marx put on the logic of exploitation and deducing all the contradictions of capitalism from this sphere.” Marini wanted to include “imbalances located in the sphere of demand”. Katz summed up Marini’s view on economic crises as a “multicausal approach to crisis, combining imbalances of realization with the falling rate of profit tendency”. Readers of this blog will know that as a proponent of a ‘monocausal’ analysis of crises, I think that Marini’s view leaves us without a theory of crisis at all.

That is not the only weakness in Marini’s version of dependency theory. He strongly promoted the idea of ‘sub-imperialism’, a category of countries intermediate between the dominated periphery and the imperialist core. Katz spends several chapters discussing the relevance of this category. In summary he says that “it helps to understand the hierarchical structure of contemporary capitalism” with “an apex of central powers and a base of dominated countries… in between are these subimperial powers trying to obtain regional hegemony.”

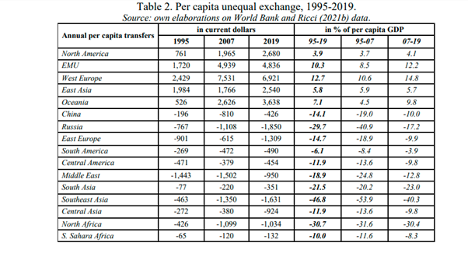

I am dubious that sub-imperialism helps us to understand contemporary capitalism. It weakens the delineation between the core imperialist bloc and the periphery of dominated countries. If every country is a ‘little bit imperialist’, if it engages in war with a neighbour over markets, resources and territory, then imperialism starts to lose its validity as a useful concept. So-called sub imperialist countries do not have sustained and huge transfers of value and resources to them from weaker economies. In our own work on imperialism and in empirical work by others, this hierarchical structure of value transfer is not revealed. India, China and Russia actually transfer much larger amounts of value to the imperialist bloc than South America. See the results of Andrea Ricci on US transfers below.

Take the BRICS, the best candidates for being ‘sub-imperialist’. There is no evidence of significantly large and long-lasting value transfers to them from weaker and/or neighboring economies. They just don’t have the financial, technological and military superiority to obtain such transfers. Can wars between peripheral countries (e.g. Iran v Iraq, Azerbaijan v Armenia) be considered imperialist in any useful way? Are these not better seen as wars between weak capitalist countries for economic and political gain?

Indeed, Katz makes the point that Brazil is not sub-imperialist as Marini saw it. It has not become a rising industrial power dominating the sub-continent. The great hope of the 1990s, as promoted by mainstream development economics, that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would soon join the rich league by the 21st century, has proven to be a mirage. These countries remain also-rans and are still subordinated and exploited by the imperialist core. And the gap between the imperialist economies and the rest is not narrowing – on the contrary. And that includes China, which also will not join the imperialist club.

Yet Katz wants to preserve the Marini concept: “In this context, intermediate formations occupy a significant place that breaks the strict parallel between sub-imperial powers and economic semi- peripheries, as the geopolitical weight of some countries differs from the integration into globalized production achieved by others. Dependency theory is very useful for understanding that variety of situations. It explains the logic of the underdevelopment and marginalization of the periphery without limiting its analysis to global polarities, and also analyses the bifurcations and differences between distinct intermediate formations.” I am not sure that it does.

What Katz’s comprehensive survey of 50 years of dependency theory does show is that Marx’s value theory of “productive globalization based on the exploitation of workers remodels the cleavages between center and periphery through transfers of surplus value.” And it is “the omission of that mechanism prevents the critics of dependency from understanding the logic of underdevelopment.”

So “reintegrating the theory of value into the explanation of dependency is also vital for uncovering the hidden skeleton of present-day capitalism. There is no invisible hand that is guiding markets, nor is there a wise state institution steering the economy. The foundation of the system is competition for profits arising from exploitation, multiplying the wealth of minorities and the suffering of the majorities. The same indignation and rebelliousness that drove the study of underdevelopment in the past orients that inquiry in the present.”

* Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. At the same time, he was a political activist in the labour movement for decades. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.

This article was previously published on Michael Roberts’ blog here.

Leave a Reply