By Halim Gençoğlu

French colonialism had profound and multifaceted impacts on African people across a vast geographical expanse, from Senegal to Madagascar, and from Algeria to Congo. French colonialism often prioritized economic gain for France at the expense of African populations. This exploitation took various forms, including forced labor, land expropriation, and unequal trade practices that favored French interests. African resources, such as minerals, timber, and agricultural products, were extracted for the benefit of the colonial power. French colonial policies sought to impose French language, culture, and values on African populations, often at the expense of indigenous languages and traditions. This cultural assimilation aimed to erase local identities and create a sense of dependency on France. Forced resettlement, the introduction of cash economies, and the disruption of agricultural practices often resulted in social instability and conflict within African communities. This included punitive expeditions, forced labour camps, and violent crackdowns on independence movements and uprisings. While French colonialism introduced Western education and modern healthcare systems to some extent, access to these services was often limited and unequal. Many Africans were denied access to quality education and healthcare, perpetuating disparities in opportunities and outcomes. Briefly, French colonial policies often exacerbated ethnic, religious, and regional divisions within African societies, leading to long-term social and political tensions that persist to this day. Arbitrary borders imposed by colonial powers continue to shape modern African states and contribute to conflicts and instability.[i]

Revealing the existence of human zoo in France

The Paris Museum of Man, officially known as the Musée de l’Homme, is a museum of anthropology and ethnology located in Paris, France. Nominally dedicated to the study of humanity, this museum displays materials related to human evolution, cultural diversity, and the relationships between humans and the environment. The museum’s exhibits include artworks from around the world and highlight biodiversity as well as the cultural heritage of different human populations. Therefore, the exhibitions cover a variety of themes such as archaeology, anthropology, ethnography, and physical anthropology. But one of the mind-blowing aspects of the museum’s collection is the display of human remains, including skulls, skeletons, and mummies from various peoples, especially Africans, which has sparked criticism. Lawyers have long argued that it is unethical to display human remains from the colonial period, especially those of indigenous people. Today, at least half of African countries, from Egypt to South Africa, are in litigation with European states as creditors. For example, France still keeps the skulls of 18,000 African freedom fighters in the Paris Human Museum, and interestingly, many of them are Ottoman subjects.

Although those who say that human skulls should be repatriated have repeatedly raised the need for these remains to be returned to their own communities for proper burial and respect for cultural practices, France still ignores these calls. The plundering and painful traces of France’s colonial legacy in Africa are still visible on the continent on various fronts. Historically, France controlled significant parts of Africa through colonization, with territories stretching from North Africa to sub-Saharan Africa. When he withdrew, he left a bloody history in many African countries from Algeria to Madagascar.[ii]

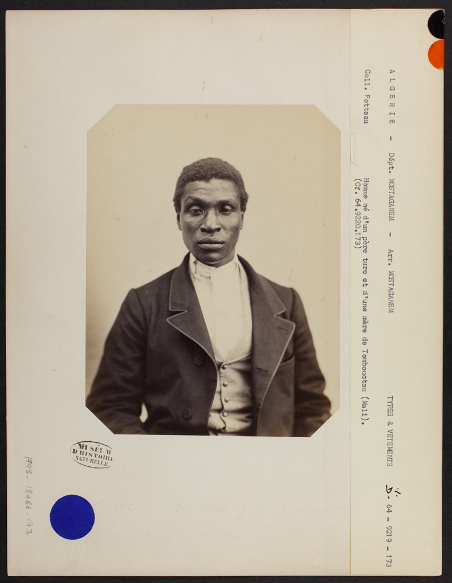

In recent years, however, there have been frequent calls for the repatriation of human remains in the Paris Museum of Man as part of broader efforts to address the residue of colonialism and promote reconciliation with affected communities. For the same reason, Germany only sent back to their homeland from Berlin in 2017 the bodies of the locals it had taken with it and used as test subjects in the Herero massacre in Namibia in 1907. Human rights advocates are collaborating internationally with indigenous groups seeking the return of these ancestral remains. However, when the records of the French Museum of Anthropology and Humanity are examined, it is noticed that there are many family members of Turkish origin in East Africa. While some of them have Turkish surnames, others have surnames of African origin. For example, most of these photographs were taken between 1860-69, and one of the people in the photographs, “Yelloub-ben-Tobji”, was 38 years old and born in Oran, Algeria. There is a note “Türk Köroğlu” on the information card. One of the most striking things is the unusual haircuts of these people. As can be seen from the photos, the front of the hair is shaved and the back reaches almost to the waist.

“Suleyman al Halabi”, 21 years old, born in Aleppo, is an Ottoman subject.

The parents of 26-year-old “Mustapha-ben-Ouarga” are Turkish.

34-year-old “Ahmed-ben-Yelloub”‘s father is Turkish, and his mother is Arab.

“Mohammed Berber”, 35, was born in Médéa. His father is Turkish, and his mother is Bornou.

“Kadour”, 30, was born in Timbuktu. His father is Turkish, and his mother is Malian.[iii]

To explain that the human museum has nothing to do with science, I’ll provide two examples. The story of Suleiman al-Halebi’s death in Egypt is very tragic. At a young age, he was an influential figure in the intellectual and cultural circles of the Ottoman geography in the late 18th century, known for his science and poetry. However, when El-Halabi’s fate intersected with killing the French commander who occupied Egypt, he chose this path at the expense of his death. His death is a poignant reminder of the intellectuals and defiance of colonial rule during that period in the region’s history. The head of Suleiman al-Halebi was displayed in a museum in Paris as part of a broader practice of collecting and displaying human remains, especially those of individuals deemed exotic or important in some way. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans marveled at the physical characteristics and cultures of non-European peoples, often viewing them through the lens of racial superiority. This has led to the collection and display of human remains from various parts of the world, including individuals deemed notable such as al-Halabi. Therefore, a scientific explanation is not possible for a skull that is displayed and humiliated as a criminal.[iv]

Al Halabi’s head was viewed by French officials as an object of curiosity or study, reflecting their interest in different cultures and their desire to establish dominance over colonized peoples. Additionally, displaying the skull in a museum is another way of understanding that perceptions of non-European peoples as inferior or primitive are real. In general, although the decision to place Halabi’s head in a museum in Paris reflects the racist and colonialist attitudes prevalent in Europe at the time, it is impossible to turn a blind eye to such barbarism today. Similarly, Sarah Baartman from Cape Town was exhibited in circuses as an object of curiosity in the early 19th century due to her physical characteristics, especially her large hips and long lips. He was subjected to inhumane treatment and exploitation, including being exhibited in a cage-like enclosure at the Paris Human Zoo, where people paid to see him. This experience was extremely traumatic and humiliating for him because Western perception turned him into an object of entertainment. Racist attitudes of the time led to Baartman being treated as inferior and exploited for profit by those who saw him as abnormal. This exploitation continued even after his death; his corpse was dismembered and displayed in museums for further entertainment. The return of Baartman’s body from the Paris Museum of Man to Cape Town in 2002, as a result of Nelson Mandela’s diplomatic initiatives, was an important moment in the recognition of his humanity and the rejection of the racism he endured. This was a step towards acknowledging the injustice done to him and honoring his memory. This example alone reveals that the Paris Human Museum is essentially a collection of corpses, founded by a barbaric mentality that has nothing to do with humanity.

This requires, first of all, that historical injustices be addressed, and an understanding of mutual respect prevails in order to establish solid relations between France and especially African countries. The discovery of human remains from Africa in the Paris Museum of Man really puts a strain on bilateral relations as it could be seen as disrespectful and enduring colonial attitudes. In his speech in 2002, Mandela said about the body of Sarah Barthman, brought from Paris, “We not only took back from France the bones of Sarah Barthman, but also our honor.”[v]

Articles and reports by contemporary scholars, journalists, and activists provide analysis of ongoing debates around the legacies of racism and colonialism in France. By engaging with a wide range of sources, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the historical contexts, ideologies, and legacies of racism in human zoos in French history and contribute to ongoing debates about social justice.[vi]

Are healthy France-Africa relations possible?

It is now essential that France take steps to rectify this by engaging in dialogue with African nations and communities, acknowledging past wrongs, and working towards the repatriation of remains. Demonstrating one’s determination to develop positive relationships based on reconciliation and dignity is the first step in this. The issue of displaying human remains in museums will continue to be criticized due to cultural, ethical and legal issues. While some museums return human remains to their ancestral communities, others continue to display them for scientific or cultural purposes. Whether the other skeletons in the Paris Museum of Man will be repatriated depends on factors such as the wishes of the communities, legal agreements, and the museum’s policies. Because the decision to repatriate and bury human remains in the Paris Museum of Man depends on various factors, such as legal considerations, cultural sensitivities, and the wishes of the communities or descendants involved. If an agreement is reached with government institutions such as France’s museums and potentially with the countries where the remains originate, it is now inevitable that France will follow a similar path as it did with South Africa and initiate the process for respectful burial of the remains, not only from a legal perspective, but also from a humanitarian perspective.[vii]

Notes

[i] Ruth Ginio, 2008, French Colonialism Unmasked: The Vichy Years in French West Africa (France Overseas: Studies in Empire and Decolonization.

[ii] Kahn, A. L. (2023). Imperial museum dynasties in Europe: Papal ethnographic collections and material culture. S. 186, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3189-7

[iii] Kuper, A. (2023). The museum of other people. S. 18. Profile Books.

[iv] Guerrini, A. (2015). The courtiers’ anatomists: animals and humans in Louis XIV’s S. 95, Paris. The University of Chicago Press. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9780226248332

[v] New David, Feore, C., Kensington Communications, BBC Worldwide Ltd, Films for the Humanities & Sciences (Firm), & Films Media Group. (2014). Museum Secrets: The Louvre. Films Media Group. http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=13753&xtid=57614

[vi] Conklin, A. L. (2013). In the museum of man: race, anthropology, and empire in France, 1850-1950. S. 49, Cornell University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/doi/book/10.7591/9780801469046

[vii] Blanchard, P., Boetsch, G., Snoep, N. J., Martin, S., Thuram, L., Musée du quai Branly, & Actes sud (Firm). (2011). Human zoos: the invention of the savage (; D. Dusinberre, C. Penwarden, S. Pleasance, & F. Woods, Trans.). Actes Sud; Musée du Quai Branly.

Leave a Reply