Venezuela has completed its presidential elections, with current President Nicolas Maduro being reelected as president. Maduro has started to gather his new cabinet.

In recent years, the country has achieved financial stability with stopping hyperinflation and stabilizing the currency exchange rate. The oil industry continues to be the centerpiece of the economy, with a limited sanctions relief prior to the elections.

Given that the US, till today, has not recognized Maduro’s victory, its future is uncertain though.

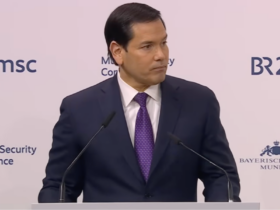

Willian Rodriguez is not only member of the Venezuelan parliament but also member of its commission for oil and energy.

In interview, Rodriguez describes in detail the challenges from sanctions as well as home-made errors, calling for changes in Venezuela’s oil and economy policy.

You are a member of the Energy and Petroleum Commission. How did the sanctions affect this particular sector?

Look, whoever reads the unilateral coercive measures will find a declaration of war on Venezuela.

The United States is very clear that they can seize any property in Venezuela, that they can freeze accounts, that they can expropriate ships, that they can imprison anyone they want. Only a country at war can do that. The United States has declared war on Venezuela.

The Anti-Blockade Observatory of the International Center for Productive Investments in Venezuela, just around the corner here, has calculated that these unilateral coercive measures have caused approximately $740 billion in damage to the Venezuelan economy.

In what period?

Since 2015, when the US declared us an unusual and extraordinary threat. This is the famous Obama decree.

To give you an idea of the scale: the Venezuelan Bolivarian Revolution invested $580 billion in its first decade to close the gap between inequality and poverty. Literacy campaigns were carried out, health programs created, numerous universities founded.

Then in 2017, we had practically no oil sales. Imagine that for a country whose income comes at 98% from oil sales and which has practically no export revenue for a year.

One of the most important achievements of Comrade President Nicolás Maduro is that he has kept the country running. Despite the blockade, the state has functioned, and peace has been maintained.

Now there is a process where some sanctions are being lifted and some licenses are being granted. How do you assess this process?

Well, I have my opinion on the licensing process. In colonial times, the Guipuzcoan company existed in Venezuela. No Venezuelan, no power, no colony could do business between Venezuela and Europe or the world without passing through them.

Today, the United States Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is the new edition of this Guipuzcoan company. Even Venezuelans who want to do business with Venezuelan oil must apply for a license from OFAC. It is nothing less than a colonial mechanism that, as Comrade President Nicolás Maduro has described it, aims to control those who do business in Venezuela.

With the license, they have simply made the entry of gringo transnationals and their European partners more flexible.

Of course, in a situation of blockade as terrible as the one we are facing, the country will take advantage of all the opportunities that open up due to its energy needs and its obligations to its partners in the world.

Venezuela tried to overcome the blockade by cooperating with other countries such as Russia, China and Iran, especially in the oil sector. Is this not enough to avoid or replace the United States as a partner to circumvent or attack the blockade?

First of all, you have to take into account that our entire oil industry was made by the gringos. From the smallest screw to catalytic towers and reactors, everything is MADE IN USA. Therefore, the blockade has done us a lot of damage.

The vision of Hugo Chavez to diversify the Venezuelan energy market and to build a whole world of alliances to invest in the largest reserves in the world, that is, in the Orinoco oil belt, which today bears Hugo Chavez’s name, deserves great respect. These alliances have allowed us to survive this blockade.

These countries have helped a lot, not only with their veto power in the United Nations, but also with their staff. I must mention Iran in particular.

When we ran out of gasoline, the Iranian government sent oil tankers. The first two tankers were seized by the United States and auctioned off as loot. A truly unusual thing that violates all international rules on international trade.

Iran seizes American tankers to maintain trade with Venezuela

But the Iranian government did not give in and did exactly the same: it seized two US ships in the Strait of Hormuz and declared that it would respond in kind. And from that moment on, gasoline began to arrive in Venezuela.

It should be remembered that Venezuelan oil production temporarily dropped to 350,000 barrels a day. That is practically nothing. And of course, there was no gasoline, no fuel, no diesel in the country to keep the vehicle fleet moving, to transport food, to maintain domestic trade. This aid was really important.

The Chinese then sold us the catalysts. The catalyst that had been used here until then was of North American design. Iran provided the planes to transport these catalysts.

But does this cooperation offer a sustainable perspective in which Venezuela will not be forced to sell its oil to the United States in the future?

Look, the reality of the energy market is complex. For example, Russia’s so-called special military operation has put us at a great disadvantage. Because when the US basically takes over Europe and forces it to commit energy harakiri by imposing sanctions on Russia, Moscow is forced to consider what to do with its oil and gas.

Russia has turned to the other side and built an energy alliance with China. This has hurt us because we sold medium and heavy crude oil to China.

Freight is very important in the cost formula for determining the selling price of crude oil. This put us at a considerable disadvantage, because the transport route from Russia to China takes practically just a few days.

What is happening to us with the North American energy market is, of course, that it is much cheaper for us to send two million barrels to the United States, which will arrive in five or six days, than to send them to China, where they will arrive in 45 days. It is a market reality.

Now it is important to say that Venezuela has built the mechanism to not depend exclusively on the North American market and that we must advance a new marketing policy that allows us to break the one-million-barrel barrier that we are currently close to. Then there will be a country that supplies derivatives such as gasoline, diesel, aviation fuel and jets for the entire southern border of Colombia, which for decades lived off the smuggling of fuel from Venezuela, for the north of Brazil, which is much cheaper than what we supply fuel that they obtain from their refinery park in the south of the country. For the entire Caribbean, where Petrocaribe must once again play a prominent and important role, and of course also for Mexico.

Mexico, which is starting up its Dos Bocas refinery, still has a deficit of almost two million barrels per day of derived fuels. He points out that Venezuela must act quickly to optimize its refining industry to obtain the crude oil, that is, the medium crude and the light crude, located in the north of Monagas and Lake Maracaibo, and escape the difficulty of establishing ourselves in the fuel supply, becoming a reliable and permanent supplier in the futures market of these countries.

Is there already a dialogue or have you started talks with Mexico, for example, about this project?

In Mexico, the opposite has happened to what happened in Venezuela. Mexico has gone from onshore production to offshore production. And in that migration, there were no longer medium and heavy crudes, and there are mainly light crudes. The opposite happened in Venezuela, since we neglected our aforementioned medium and light crude fields in Lake Maracaibo, in northern Monaga and in part of Anzuate. And now we are left without feeding our refineries. So, there is a business opportunity that both countries are interested in. We have to break a barrier that says that the Mexican market has never looked south, it has always looked north. We went there two years ago to tell it: “Look, start looking south.” I think President López Obrador understood it, he received the Venezuelan delegation.

We met personally with his Minister of Energy. He took very good care of us. And now, there is a process of talks. There has always been a more technological and scientific exchange than in real commercial relations. We hope that now, together with the new president and the team that manages Petróleos de Venezuela, we can break the barrier of always looking north and ensure a supply that would be of great importance for Venezuela and of great benefit to Mexico.

Venezuela is experiencing an economic renaissance, the economy has recovered, there is talk of growth of 8%. How do you assess this?

Look, a long-time economist who was not exactly Chavista, Asdrúbal Batista, a member of the Venezuelan Academy of Sciences, wrote a book titled ‘Rentier Capitalism in Venezuela’. And in this book, he expressed very clearly, with figures and statistical data that our private company never contributed more than 2-3% to the gross domestic product. That is, we had parasitic businessmen who wanted to get their hands on the oil revenues.

That changed suddenly with the unilateral coercive measures that came with the blockade. And of course, when we lifted the restrictions on the circulation of dollars to alleviate the economic crisis that had been imposed on us, the economy technically stopped being dependent on the dollars that came from the oil industry.

This led to a change among Venezuelan businessmen and there was a year in which the state did not provide dollars to private companies because it did not have any dollars.

And the businessmen put the dollars that they had withdrawn from Venezuelan companies in the past into a hard currency to protect their reserves, and they had to buy their raw materials on the market to maintain their private companies. This then allowed us to, as we Venezuelans say, reboot the Venezuelan economic model.

That Venezuela today, which historically in the Fourth and Fifth Republics was a country whose agrarian economy was ‘port agriculture’, that is, food had to be imported from outside. Today, this is not the case and that we produce 97.98 percent of the food consumed by Venezuelans. This is a historic milestone that goes beyond the efforts of the national government, the level of dialogue and understanding with Venezuelan businessmen and the building of foundations so that the economy is truly an economy not exclusively linked to oil income.

That is a big part of our growth. Of course, the country has fallen very low. A country that previously was receiving $70 billion in revenue fell to get $700 million. And we hope that in the industrial field too, the industrial apparatus that the country has and that has shrunk brutally, begins its reactivation, that the oil industry also breaks with this model of buying everything from abroad and begins to realize what potential there is in this country and then take advantage of the sectors that produce.

Today, for example, we continue to buy piston pumps externally. And in Zulia there is a huge factory where all these pumps are built, but well, we are not finished linking them so that we do not buy more from abroad and buy internally.

And this is a process that must be advanced rapidly so that the Venezuelan industrial park is also integrated into this economic growth with great force and great sustainability, because that is the most important thing. What the oil industry has done during this period of economic blockade, economic war is really significant. Today our 39 oil tankers are blocked, that is, they cannot reach any port in the United States, Canada or Europe.

We need to have them here, pay the freight to market and outsource international trade. To continue to drive growth, we had to become oil pirates. Have our workers go out every day at 4 a.m. to put on their knickers, their uniforms and their boots to keep this country running, not just in the oil area, in the electricity supply area, in the water supply area, etc. In the greater area, in all these areas, you have to recognize that they are the new heroes and heroines of this country.

Because the salary is one of the lowest salaries and one of the debts of the Venezuelan revolution for failing to restore the purchasing power that we had in the face of unilateral coercive measures.

Of course, not everything is the responsibility of these measures, there are some mistakes, there are some things we have done wrong, the problem of corruption has caused us profound damage economically and from an ethical and social point of view, from the point of view of moralizing our power. We have these debts that we have not paid off.

The dollarization that practically exists here has, in my opinion, managed to reduce inflation and practically eliminate it, but at the same time, does it not mean a loss of national sovereignty in terms of managing the economy?

Look, we have the loss of sovereignty. It is the low salary that our job has.

The low salary?

Yes. Why am I telling you this? Well, because it is not justified that here you can pay in dollars for what we consume, but our workers do not earn in dollars. They charge in bolivars and when they do the equivalent, they pay an extremely low salary.

But the fact that the revolution has already recorded almost two years of sustained growth in the industrial economy, in line with the forecast that we will grow by 8% this year, is really significant and that Petroleos Venezuela is breaking the million barrel barrier, must help us break a monetarist policy that places more importance on controlling inflation and keeping the exchange rate stable than on using the purchasing power of our workers.

This is because we are even contradicting one of the golden rules of capitalism, which states that in order to increase consumption, we must increase the purchasing power of important sectors of society.

The problem now is that we have a hypertrophied state, we have an extremely large bureaucratic apparatus. We have almost the same number of civil servants, but no, we have twice or three times as many civil servants as Brazil, a country with almost ten times the population of Venezuela.

That’s a testament to the hypertrophy of this state, and when you have a payroll of 4.5 million employees and you put a zero on the payroll in dollars, you have to have a guarantee that you’re going to meet that, and that was the great constraint that we had.

And we did not dare to develop a model that would effectively allow us to significantly increase our salaries, and we were in the process of creating bonuses to mitigate the extent of the economic crisis and the lack of purchasing power of our workers but let us pay off this debt.

This is a major debt, and every self-respecting revolutionary must know that we have failed here.

How do you see the perspective of Venezuela?

A new period of revolution must begin on the 29th and this period must first recognize previous errors. A problem that is very dangerous and very difficult to solve because it is not easy either is the break with the economic model in which we are more interested in the stability of exchange than in the purchasing power of our workers.

This model is now sold out. We must demand the performance and recognize the efforts of our employees. This is a social debt that we revolutionaries have.

And secondly, there must be a new change in the exercise of power. We have a model in which everything has been centralized and there is almost no room for debate and criticism.

That is why we need to create spaces where we revolutionaries with a deep vision can debate the future of this country and the development of its oil industry in the next 50 years, and we need to do that together with our universities, with the opposition, with our unions, but fundamentally with our professionals, our students and our workers. This is an important debate that has not yet taken place in the country and we need to discuss it.

Our oil industry, its structure, its business model is still the same business model that the gringos who were here 100 years ago left us. This is another rupture that needs to be made there and, of course, the size of the state needs to be redefined, not to weaken it but to make it stronger and more efficient. This is a debate that generates great fear and great concern because it has complex implications.

And the other element that also has to do with Essequibo. The Essequibo is a hot potato. We have passed the law for the incorporation of this territory into Venezuela. Many of us who study the issue propose an unconventional migration for the oil extraction of this territory, in my particular case I know the oil belt.

The strip is delimited by the imaginary line that the English Empire has drawn since 1899 to dispossess us of this land, and which we have definitely said we do not accept, and if we do not accept it, that means: well, we exercise sovereignty in this area. These are the things that are pending, that are still latent.

Leave a Reply