The report published by one of Germany’s prominent economic research institutes, Ifo (Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München e. V.), on September 5, 2024, is titled “Deutsche Wirtschaft steckt in der Krise fest” (The German economy is stuck in crisis).

The report identifies the crisis as primarily a structural one, and it lists five structural factors: Decarbonization, digitalization, demographic change, energy price shock and the changing role of China in the global economy. “These are putting established business models under pressure and forcing companies to adjust their production structures” writes the report, and “Germany is particularly affected by these changes compared to other countries.”

Recently, Volkswagen announced the plan of closing plants in Germany. This is for the first time in history. For many, this is alarming. According to Spiegel, there is currently a gap of four to five billion euros in the financial plan of Volkswagen and its Commercial Vehicles brands. The company’s CFO, Arno Antlitz, explained the situation as follows: “We cannot sell around 500,000 cars, which is approximately the production of two factories. This has nothing to do with our products or bad sales performance. The simple truth is this: We simply no longer have the markets to sell them”.

Matthew Karnitschnig, in his September 19 article in Politico, writes that Germany is “already the weakest economy in the G7” and summarizes the long-discussed structural problems as follows:

“After years of turning a blind eye to what the rest of the world could plainly see, Germans are slowly coming to terms with the reality that they are in deep trouble as the four horsemen of their economic apocalypse come into view: an exodus of major industry; a rapidly worsening demographic picture; crumbling infrastructure; and a dearth of innovation.”

Offshore trend

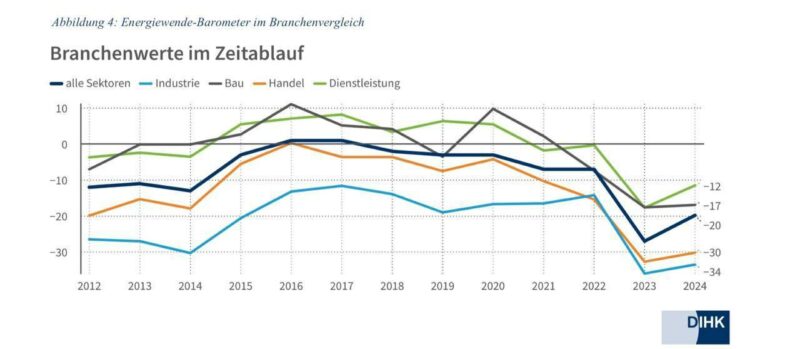

The current situation related to the issue of “deindustrialization” in Germany was starkly highlighted by the results of surveys conducted by the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (Die Deutsche Industrie- und Handelskammer – DIHK) between June 10-30, 2024, involving 3,283 companies. In the report titled “Energiewende-Barometer 2024” (Energy Transition Barometer 2024), the words of an industrial company executive from Western Germany were quoted as follows: “De-industrialization in Germany has begun, and it feels like no one is doing anything about it”.

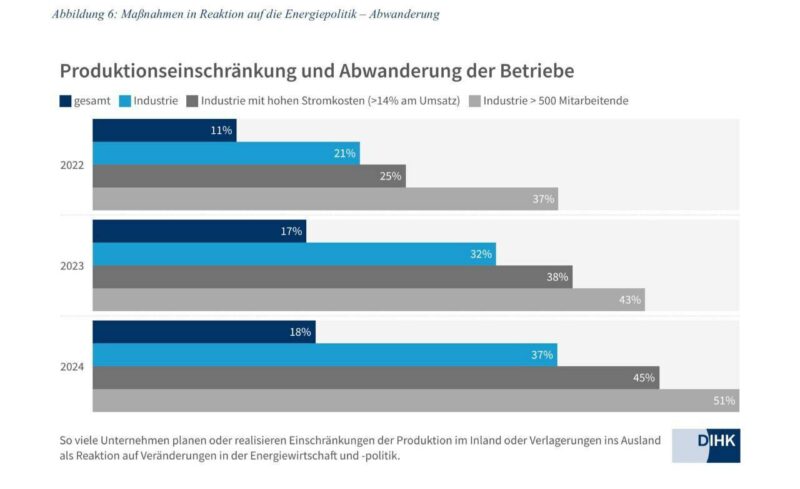

As seen in the table below, the tendency to move workplaces outside of Germany has strengthened in 2023 and 2024. This trend is much more pronounced in the industrial sector, especially among companies with more than 500 employees and those that operate with high electricity costs.

The report asks companies about the process referred to as the “energy transition” (Energiewende) with the question: “How do you evaluate the impact of the energy transition on the competitiveness of your company?” On a scale from minus 100 for “very negative” to plus 100 for “very positive,” the average satisfaction score among responses from 3,283 companies across all regions and sectors was minus 19.8.

“Existential challenge” for European economy

When placing the structural issues in Germany’s economy, the “locomotive” of the European Union, in a broader European context, the September 2024 report by former Goldman Sachs banker, former president of the Italian central bank, and former president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, may be enlightening.

The report is written at a time when virtually no EU economy is growing by more than 1% annually, and the average for the Eurozone is just 0.2%. Draghi describes the current state of the European economy as an “existential challenge.”

Draghi identifies “low productivity” as one of the two main problems. He writes:

“EU economic growth has been persistently slower than in the US over the past two decades, while China has been rapidly catching up. The EU-US gap in the level of GDP at 2015 prices has gradually widened from slightly more than 15% in 2002 to 30% in 2023, while on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis a gap of 12% has emerged. The gap has widened less on per capita basis as the US has seen faster population growth, but it is still significant: in PPP terms, it has risen from 31% in 2002 to 34% today. The main driver of these diverging developments has been productivity. Around 70% of the gap in per capita GDP with US at PPP is explained by lower productivity in the EU.”

The second is the fact that Europe has fallen short to catch up with the technological changes:

“Technological change is accelerating rapidly. Europe largely missed out on the digital revolution led by the internet and the productivity gains it brought: in fact, the productivity gap between the EU and the US is largely explained by the tech sector. The EU is weak in the emerging technologies that will drive future growth. Only four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European.”

Compared to the US, “EU’s global position in tech is deteriorating: from 2013 to 2023, its share of global tech revenues dropped from 22% to 18%, while the US share rose from 30% to 38%.”

In conclusion, Draghi writes: “Europe urgently needs to accelerate its rate of innovation, both to maintain its manufacturing leadership and to develop new breakthrough technologies.”

Mittelstand in danger

Mark Schroers in Bloomberg on September 6 writes that “A recovery in the manufacturing sector is key to reviving Germany’s economy, but so far there are no signs of a real turnaround — adding to concerns that its troubles are more structural than temporary.”

On those structural factors, Warner writes the following: “Many of the problems that afflict the German economy – poor levels of business investment, stifling red tape and bureaucracy, Nimbyism, an increasingly workshy labor force sustained by overly generous welfare, dilapidated infrastructure and an aging demographic”.

Economist Jeremy Warner says that these are quite similar to those of the UK, but Germany goes further than the UK concerning the problems based on low rates of investment. Since “Germany’s strengths in manufacturing have traditionally been a much larger element of GDP than in the UK”, “depressed levels of business and housing investment” becomes now the key reason for German stagnation.

This also reflected on the fact that Germany’s Mittelstand (medium-sized family-owned businesses) is “in danger of being left high and dry” as Warner notes.

According to many analyses, the situation in the German economy is structural and difficult to treat. That is why the expression used for the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 19th century is spreading for Germany: The sick man of Europe.

Leave a Reply