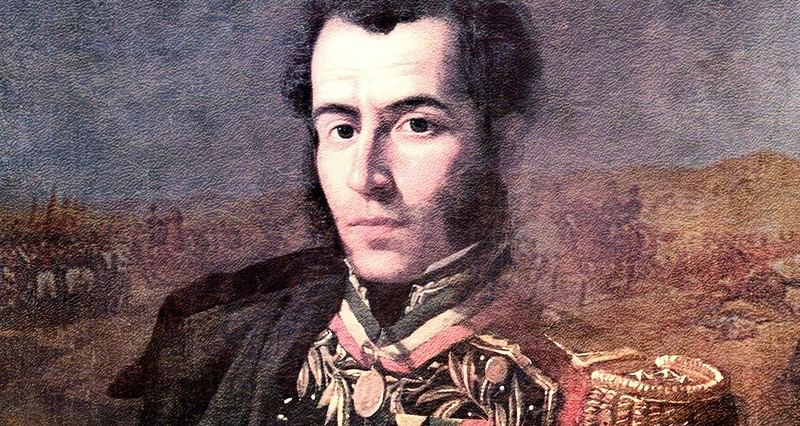

By Sergio Rodriguez Gelfenstein

His father’s and mother’s lineages indicated that Antonio José should first embrace a military career; his own father became commander-in-chief of the Cumaná Army. Before that, the sudden death of his mother and the new marriage of Don Vicente had a powerful influence on the life of the boy, who adopted an introverted and taciturn personality.

He began his studies at the School of First Letters of Cumaná but was soon transferred to Caracas, the city where, under the protection, guidance and influence of his godfather, the cleric Antonio Patricio Alcalá, he entered the School of Engineers, where he learned geometry, algebra, trigonometry, surveying, fortification and artillery.

The events of April 19, 1810, surprised him in Caracas. The flash of events would have a notable influence on the young man from Cumaná, who put his studies on hold and decided to return to his hometown, which had joined the revolution and created its own Government Board.

Another priest, his uncle José Manuel Sucre, instilled in him at the age of 15 the patriotic fervor that he would acquire at that early age and perpetuate for the rest of his life. There was no more time for study; he felt that Venezuela required his services, and he devoted himself to a military career, assuming the responsibility of a self-taught education.

His campaigning life began in 1811 and would not end until his death. He had his baptism of fire at the age of 16 during the capture of Valencia, a bloody battle that ended in victory despite the Republican ranks. In these conditions he met Francisco de Miranda, with whom he had an almost imperceptible encounter. In this context he also met Colonel Simón Bolívar who served under Miranda.

From then on, and after the suffering and pain caused by the extermination of his family in 1814 at the hands of the Spanish leader José Tomás Boves, his sadness became more pronounced, and his solitary character took on a character that he would never abandon.

Sucre turned to a military career, driven by the pain of family loss, the impetus of his youth and the patriotic fervor that he would embrace for the rest of his life. He was soon promoted to lieutenant, in 1813 to captain under the command of Mariño and in 1815 to commander, directing the artillery at the siege of Cartagena. In 1817 he received the rank of colonel. He was only 24 years old when Vice President Zea, in the absence of Bolívar, made him Brigadier General and entrusted him with the command of the British Legion in Apure.

His learning was slow, difficult and systematic. Being very active and shrewd, as well as bold, his timid personality goes unnoticed, especially when his first training takes place alongside already established leaders such as Bermúdez, Piar, Mariño, Monagas and Sedeño. During this period his military talents are more evident in the work of the General Staff where he organizes the work, gives instructions and advice, taking advantage of his disciplined conduct and his shrewd sense of the future, all of which breaks the logic of his impulsive and vehement leaders.

But the truth is that Sucre’s rapid rise to the highest ranks of the military hierarchy occurred in the context of the war, a higher school of military training that precipitates promotions, and thus, in the heat of combat – from an early age – he began to show his extraordinary heroism, his great tactical ability and his proverbial strategic genius.

Sucre’s patriotic sentiment was faced with the manifest disagreements between his eastern bosses – to whom he had been subordinate – and Bolívar, but at the time of making a decision, together with Urdaneta, he did not present any doubt when in Cariaco they tried to create a caricature of a republic that denies the leadership of the Liberator.

Against his will, he was forced to take a public position in the face of the endless political pettiness of the eastern caudillos who fought Spain to achieve the freedom and independence of their small fiefdom in the eastern regions of Venezuela. When the rivalry reached dangerous levels for the unity of the republicans in their fight against the Spanish empire, Bolívar entrusted him with mediating with Mariño to seek the unity of the Venezuelans. Sucre fully fulfilled the mission, he met with his former boss, they argued, at some point in heated tones he tried to convince him in political terms, exposing a virtue that Mariño did not possess. However, he achieved his objective, the eastern general decided to subordinate himself to the Liberator by placing himself under the orders of Arismendi.

On two more occasions he was forced to assume the responsibility of mediating in the internal struggles between Mariño and Bermúdez, and in both conflicts – perhaps much more complicated than the actual war with the Spanish army – he emerged victorious. Thus, he demonstrated his political and diplomatic skills, which were added to the undoubted military capabilities that he demonstrated in combat.

In these struggles, Sucre demonstrated a great ability to maintain balance, understanding and assuming always positions free from any quarrel, rejecting disputes and conspiracies while promoting the attenuation of disputes and disagreements in the patriotic camp.

But he has no doubts about where he should be. In a letter dated in Maturín on October 17, 1817, in which he reports on one of those negotiations that he was forced to assume with displeasure, having to dialogue, negotiate and convince Mariño by order of the Liberator, he expresses his total and absolute loyalty to him.

After efficiently and effectively fulfilling a mission entrusted by Bolívar to obtain weapons in Saint Thomas, which were delivered to the Liberator himself in Cúcuta, Sucre began to act directly under his orders. At the time of his arrival in this city of New Granada, Bolívar was not there, but a few days later, on July 11, 1820, when he arrived in that city, a delegation made up of high-ranking officers, among whom was Sucre, went out to receive him. O’Leary, who did not know him, asked Bolívar who this “bad horseman” who was approaching was, to which the Liberator responded, already looking to the future: “He is one of the best officers in the army; he combines the professional knowledge of Soublette, the kind character of Briceño, the talent of Santander, and the activity of Salom; strange as it may seem, his abilities are not known nor are they suspected. I am determined to bring him to light, convinced that one day he will rival me.”

No one imagined that Bolívar would “bring him to light” so soon. At first, he immediately incorporated him into the General Staff and then named him interim Minister of War. In this circumstance, a new scenario opened up in the independence struggle. In addition to the frontal attack on the battlefields, the possibility of seeking an agreed solution to the conflict began to emerge. Both sides began to prepare for this unprecedented confrontation at the negotiating table. On the patriot side, Bolívar had no doubts: it would be Antonio José de Sucre who, as plenipotentiary representative, would lead the Colombian delegation. He would put his diplomatic skills to the test in the most complex event that the republic had had to face in its short history.

It was his first mission as a diplomat of the republic, and he carried it out successfully. To unleash all his creativity and autonomy not only in thought but also in action, during the negotiations, the Liberator chose to retire to Sabanalarga, a few kilometers from Trujillo where the conclave was taking place. Sucre shone in the debates that led to the signing of the treaties, displaying his talents not only as a soldier, but also as a politician and statesman when he was only 25 years old.

On January 11, 1821, already in Bogotá, Bolívar appointed Sucre as commander of the Southern Army that operated in Popayán and Pasto, but later this decision was annulled when the Liberator, understanding the demonstrated capacity of the young man from Cumaná, considered it appropriate to order him to higher missions. Thus, he was sent to Guayaquil with larger-scale tasks when he was commissioned to incorporate into Colombia that province that had been freed from Spanish rule in October of the previous year.

On April 6, he arrived in Guayaquil and on the 15th, representing Colombia, he signed a treaty with that province, which maintained its autonomy but remained under Colombian protection. Sucre was authorized to begin operations after the province granted him the resources it had. On August 19, he obtained an important victory in Yaguachi against the forces of Marshal Melchor Aymerich.

In this situation, Sucre asked the Governing Board to make a definitive decision on the incorporation of the province into Colombia, but there were still doubts in some of the members of that body that did not allow the majority’s request to be carried out. Without wasting time, faced with indecision, he undertook new operations but was defeated in Huacho on September 12, being forced to retreat to Guayaquil to reorganize his army while waiting for new reinforcements to be sent from Colombia.

But a new threat darkened the outlook for the new province: forces sent from Peru arrived in Guayaquil with the intention of taking it over and placing it under Peruvian sovereignty. The scenario was bleak, the possibility of a confrontation between patriotic forces had been put on the table, three currents fought for control of the important port: those that favored Colombia, those that planned to be independent and those that pushed Guayaquil towards Peru. Demonstrations began and decisions were even taken for and against each of the proposals.

Once again, Sucre had to use his best diplomatic skills to convince the warring parties that there was a common enemy against which forces should be united and once this enemy was defeated, the differences regarding the political future of the province could be settled. Sucre, through General Tomás de Heres, negotiated directly with the Peruvian authorities and obtained their support with troops under the command of Colonel Andrés de Santa Cruz. All these facts that emerged from Sucre’s political, diplomatic and military capacity, allowed public opinion to turn in favor of Colombia, allowing him to restart military operations against the Spanish enemy, also consolidating his leadership and the recognition of Guayaquil.

The military operations were designed based on the creation of the United Army with soldiers from various republics. The actions began at the end of the first month of 1822. On April 21, he took Riobamba, on the 29th he continued his march and on May 2 he occupied Latacunga to wait for reinforcements from Panama. On May 13, he resumed operations heading to Quito, at the same time that he sent a contingent to prevent the Spanish troops from Pasto (the last Spanish bastion in Colombia) from reinforcing the royalist group. Under these conditions, he presented battle to the royalists at the foot of the Pichincha volcano, causing them a resounding defeat on May 24, liberating Guayaquil and all the territory that today makes up the Republic of Ecuador, thus creating optimal conditions for his entry into Colombia.

In recognition of his merits, on June 18, Bolívar promoted him to division general and named him intendant of the department of Quito, one of the three that, along with Venezuela and Cundinamarca, made up the Republic of Colombia. Dedicated to government work, he developed an intense political and public management activity that resulted in important benefits for the people of Ecuador.

In response to Peru’s call for Bolívar to address the country’s anarchy, and the Liberator being prevented by the Congress of Colombia from immediately going to Lima, Sucre was appointed to go to Lima and negotiate a treaty of alliance with Colombia. Likewise, Sucre was to agree with the government of that country on an operational plan that would lead to the total defeat of the Spanish in South America. In practice, he acted as Colombia’s plenipotentiary diplomatic envoy to Peru. On May 10, 1823, he arrived in Lima and until September 1 of the same year, when Bolívar arrived, he acted as Colombia’s highest political, diplomatic and military representative in Peru.

During those days, preparations were being made for operations to be carried out in the south, particularly targeting the intermediate ports. Faced with the contingency and without being able to give an opinion on the success or failure of the plans designed, Sucre was forced to march with the Peruvian troops towards Arequipa. In addition, he proposed an alternative to the Peruvian plan, recommending to President Riva-Agüero that if it was decided to send the entire army to the south, the necessary measures should be taken simultaneously to create a new army made up of 3,000 soldiers under the command of a capable leader, to prepare to carry out operations in a new campaign in the future. Sucre, with his great military capacity and his long-term vision, was planning to continue the war in case a situation occurred – as unfortunately occurred – that meant the defeat and disorganization of the army in the south.

On May 30, Sucre was appointed by the Peruvian Congress as commander of the united army and later as supreme military leader. When he accepted this appointment, he stipulated that this appointment only have jurisdiction over the territory of the war. The southern campaign was a failure, it was poorly planned, the patriots were defeated and had to return to Lima, after a brilliant retreat designed by Sucre that prevented the collapse of the independence forces.

With the arrival of the Liberator in Peru, Sucre immediately joined his General Staff, participating in the battle of Junín and in the subsequent occupation of the vast territory that until then had been under Spanish occupation. In this situation, Bolívar decided to return to the coast to take up state responsibilities. In this situation, and in response to the order of the Colombian Congress to withdraw the Liberator’s power to command the Colombian army and to annul the extraordinary powers that had been conferred on him to wage war, Bolívar appointed him to lead the final operations of the liberation campaign in Peru. Although he had decided this long ago, this disposition was now institutionally formalized. The time of Simón Bolívar the Liberator as head of the Colombian Army in Peru was over. The time of Antonio José de Sucre, aged 29, had arrived. What happened next is history: the victory at Ayacucho was due in large part to his strategic vision, his tactical sagacity and his operational management.

On February 10, 1825, the first anniversary of Bolívar’s dictatorship in Peru, the Constituent Congress met in the midst of the greatest solemnity. The Liberator reiterated that it seemed dangerous to him to grant any man a “monstrous authority.” He then invoked the victory of Ayacucho that “had healed the wounds in the heart of Peru and had broken the chains that Pizarro had placed on the sons of Manco Capac.”

He ended by formally installing the Congress of the Republic, but not before informing that his responsibilities now were to surrender Callao and contribute to the freedom of Upper Peru, after which he would return to Colombia to inform the representatives of the people about the fulfillment of his mission in Peru, its independence and the glory of the Liberation Army.

On that same day, February 10, 1825, the Constituent Congress of Peru, in recognition of the General in Chief of the United Army, Antonio José de Sucre, granted him the title of “Grand Marshal of Ayacucho” for the memorable victory obtained in the fields of that name.

200 years after that memorable date, the country must return to history to exalt Sucre, one of its most notable and prodigious sons, who on the battlefields and in diplomacy, in war and in peace, transmitted values of dignity and honor that today form the foundation and pride of the new Venezuela.

Leave a Reply