By Orçun Göktürk, President of the Turkish-Chinese Studies Center, from Beijing / China

The elections in Japan have concluded. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) once again managed to remain at the center of the system and secured a victory that strengthened its power beyond expectations. The coalition led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) won 352 of the 465 seats in the House of Representatives. This figure is well above the two-thirds majority required to override potential vetoes from the upper house.

Takaichi ran an explicitly nationalist-conservative centered campaign, appealing to voters unsettled by economic difficulties and rising regional tensions. With strong popularity among youth, women, and the elderly, the election results clearly tilted in favor of the LDP.

One-Party rule

Contrary to common liberal narrative, Japan is in fact under a one-party system. Since 1955, with only two brief interruptions, the same political party has governed Japan: the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). That amounts to nearly seventy years of dominance. Generations have changed, the world has changed, the Cold War ended, China rose, but power in Tokyo did not change. On the surface, one sees “stability,” but a deeper look reveals a different picture.

Voter turnout once again remained low. For a long time, participation has hovered in the 40–50 percent range, indicating that a significant portion of society remains distant from politics. Despite this, Japan continues to be presented in the Western narrative as a “model liberal democracy.” If you are a loyal U.S. ally, the “democracy” standard can be somewhat flexible…

The latest elections in Japan were not, in fact, an “ordinary process”. They were the result of Takaichi’s deliberate political gamble. Prime Minister Takaichi decided to go to the polls in an atmosphere where intra-party balances were strained, economic dissatisfaction was increasing, and Japan’s room for maneuver in foreign policy was narrowing in parallel with the decline of U.S. hegemony. The decision was risky, but it seems so far Takaichi’s calculations proved correct.

A strategy of escalating intra-party tensions

Within the LDP, a clear tension is visible between the traditional center-right pragmatic wing and the more Atlanticist, nationalist, so-called security-focused, and anti-China wing.

Rather than softening this tension, Takaichi chose to sharpen it. She heightened security rhetoric. In 2024, the country doubled the share of its military budget in national income. She brought the Taiwan card against China to the forefront in a harsher tone.

Issues such as increasing defense spending and reopening debate on Article 9 of the Constitution, which forms the basis of Japan’s anti-war and “pacifist” identity and declares that Japan renounces the right to wage war, have once again been moved to the center of politics.

Was the Abe assassination a turning point?

Let’s return to 2022. The assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe during an election campaign was recorded as an extraordinarily unusual and shocking event in recent Japanese political history. It should be noted that despite Abe’s anti-China stance, he met with Putin 27 times and did not view the Russia-Ukraine war from an Atlanticist perspective.

Japan has long been known as a country where political violence is almost nonexistent in the postwar period and where even ordinary armed violence is extremely rare. For this reason, the Abe assassination deeply shook the structure of Japanese politics. The incident not only intensified security debates but also paved the way for the nationalist line within the LDP to gain greater strength.

Under Takaichi’s leadership, the LDP chose to consolidate a more ideological and right-leaning base, even at the expense of narrowing its traditional broad coalition model. We can call this a kind of “high risk, high reward” move. Ultimately, it worked, and the election resulted in a major defeat for the coalition’s rivals. But of course, it was not without cost.

Because this strategy erodes the pragmatic balancing politics that the LDP has pursued for many years. The party has now shifted toward a more ideological, harsher, and more polarized line. At its doorstep stand countries such as Russia and China, with whom disputes persist. Its principal transoceanic ally, which “disciplined” it with two atomic bombs, remains aggressive but is itself in a period of decline.

Takaichi’s limitations

Yes, the LDP once again emerged strong from the elections. But when one tries to examine Japan’s political structure, the picture is more complex. The younger generation remains distant from politics. The opposition is fragmented and weak. The population is steadily aging.

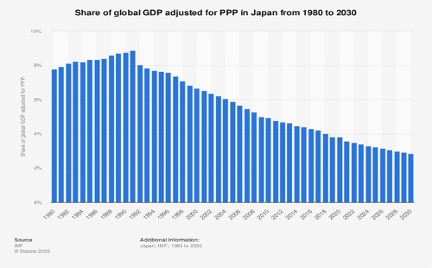

However, the main issue is the economy. According to IMF data, Japan’s share of global GDP (in PPP terms) was close to 9 percent in the early 1990s; today, it has fallen below 4 percent. In other words, its global economic weight has declined by more than half.

Figure 1: Japan’s Share of Global National Income (1980–2030, PPP)

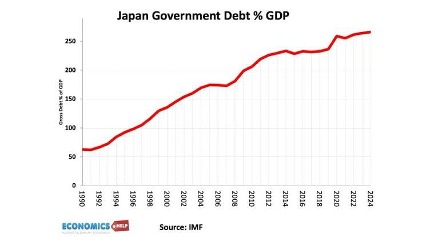

During the same period, the public debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from around 60 percent to over 250 percent, an unprecedented level. This is one of the highest ratios among advanced economies.

Figure 2: Japan’s Public Debt-to-GDP Ratio

Taken together, these two data points tell us: Japan is not failing to grow, but the rest of the world is growing faster, and Japan is sustaining this largely through an economic “balance” financed by debt.

For years, this picture was interpreted in Western literature as “stability.” Now, in the same Western mainstream media, we witness Japan’s aforementioned problems being highlighted almost daily. There is a serious gap between the reality long described by the liberal creed and Japan’s systemic problems. Takaichi’s discourse is likely to collide with the wall of crises Tokyo has long faced.

The geopolitical card played through China

China stood at the center of Takaichi’s campaign. A hardened security language was adopted, particularly over the Taiwan issue. This rhetoric clearly signals alignment, especially with a Trump-led United States. Within Washington’s “Indo-Pacific” strategy, Takaichi is seeking a distinct role for herself.

But here lies a major contradiction: Japan’s largest trading partner is China. Beijing is also Taiwan’s largest trading partner.

In other words, economic reality points to deep interdependence. Japanese industry is integrated into China’s production chain. From automotive to electronics, there are significant ties.

For this reason, adopting an aggressive geopolitical position over Taiwan carries the potential to generate economic costs. Takaichi’s other gamble comes into play here: the tension between security rhetoric and economic reality.

Beijing’s possible response

The impact of the election results on China will likely take the form of hardened rhetoric in the short term and cautious economic pragmatism in the medium and long term. Takaichi’s Taiwan-centered language, which tests China’s red line of the “One China” policy, and her steps toward increasing defense spending are being closely and critically monitored by Beijing.

However, from China’s perspective, Japan—while an extension of strategic competition with the United States—is also an indispensable economic partner. Therefore, Beijing’s response will likely not be military; rather, it will take shape through diplomatic and economic pressure and regional balancing policies. Instead of pushing Japan entirely into the opposing camp, China will likely continue a strategy of controlled tension management, taking into account Tokyo’s economic vulnerabilities.

Demographic contraction

Another major problem for Tokyo is that the country is rapidly aging. The working-age population is shrinking. Fertility rates are low. Social security expenditures are rising. Domestic demand is under pressure. Moreover, the consumption taxes that Takaichi has pledged to lower are the lifeblood of the economy.

Without resolving these structural issues, geopolitical hardening is not sustainable. Strategic ambition requires economic and demographic capacity.

Takaichi’s decision to call elections was a gamble. She won. But Japan’s structural realities have not changed.

The country’s global economic weight has diminished.

The debt burden is high.

The population is aging.

Economic ties with the “hostile” China run deep. Moreover, as Tokyo declines, Beijing continues to rise.

Under these conditions, a Taiwan-centered hardline rhetoric may provide short-term political mobilization domestically and over Taiwan. But in the long run, the fundamental issue Japan faces is not geopolitical confrontation but internal structural transformation. Moreover, Japan’s capacity to mount geopolitical challenges is in a worse state than before.

Let me emphasize again: in the early 1990s, Japan accounted for approximately 9% of world GDP (PPP); today, it has fallen below 4%. The IMF’s 2030 projection indicates that this erosion will continue. In other words, what we see before us is no longer a global giant, but a country whose slice of the pie shrinks each year, like all other G-7 countries. In addition, the public debt-to-GDP ratio has exceeded 250 percent. For a country whose productive power is declining while its debt multiplies to embark on military swaggering in the region is tragicomic.

So yes, the election result may be a victory for her and LDP.

But Japan’s real test is just beginning. Under Takaichi’s leadership, Japan is chasing an old myth. In the multipolar structure of the international system, becoming a pawn of that old myth does not align with the realities of Japan or the world.

Leave a Reply