Over the past year, Iran has been going through an extremely turbulent period. A full-scale 12-day war—which, despite the killing of senior Iranian military commanders, ultimately turned into a powerful demonstration of Iran’s missile capabilities and deterrence—was followed by severe economic turmoil that led to a sharp depreciation of the national currency and widespread public protests. In addition, a quasi-coup attempt by supporters of Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran’s exiled shah, unfolded over two nights in various cities across the country, particularly in the capital, Tehran, involving extreme forms of violence, including killings, the burning of public and private property, and attempts to seize military zones around the city. Finally, the looming shadow of an all-out war with the United States, created by the unprecedented mobilization of American military assets toward the Middle East, has also been among the major developments in Iran in recent months.

There is no doubt that a significant part of these events is the result of the impact of the crippling sanctions imposed over the past two decades by the United States in connection with Iran’s nuclear file—sanctions that, over a twenty-year period, have reduced Iran’s macroeconomic capacity and weakened the government’s ability to manage economic conditions. Nevertheless, despite this reality, the crises of recent months appear to have pushed Tehran toward serious managerial changes within the country and have also affected the configuration of domestic politics and governance. As the acute phase of the crisis subsides, it can be expected that in the coming months there will be major changes both in the way internal issues are managed and in the dominant political discourses within domestic politics.

Security Policies

The 12-day war, along with the United States’ hesitation to engage in direct military intervention against Iran—despite the pressure and interventionist rhetoric associated with Trump—has pushed policymakers in Tehran toward the conclusion that investment in the country’s defense policy constitutes a core element of national survival and a guarantor of security against external aggression. Accordingly, there is little doubt that in the period ahead Iran will witness more substantial investments in the defense sector, and, at the technological level, a move toward deeper strategic cooperation with Beijing and Moscow.

On the other hand, another outcome of the crises of the past nine months has been the undeniable weakness of Iran’s security apparatus in anticipating acts of sabotage by terrorist cells linked to foreign intelligence services. Both during the 12-day war and in the sabotage operations of January 8 and 9 in Tehran and other cities, armed groups trained by Mossad and the CIA played a significant role. This involvement has prompted Tehran’s authorities to move toward a serious reassessment of the performance and effectiveness of the country’s security institutions.

It appears that in the coming months Iran’s security structures will undergo notable transformations. One indication of this trend has already been seen in changes to the structure of the Supreme National Security Council, the highest coordinating body among the country’s security institutions. The establishment of a Defense Council chaired by Admiral Shamkhani—who serves as the military and political adviser to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader—should also be analyzed within this same framework.

In the months ahead, significant changes can be expected in national security protocols, in the protection measures for political and military figures as well as nuclear scientists, and in the level of coordination between military forces and civilian state institutions.

Implications for Tehran’s Foreign Policy

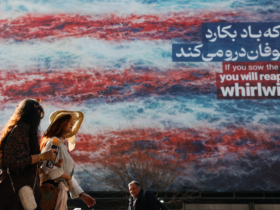

The experience of the United States’ failure to honor any political negotiation, combined with NATO’s full-scale cooperation with Israel in carrying out critical strikes against Tehran, has pushed Iranian officials toward a serious reassessment of how they view the future of political engagement with the West and the United States. The direct confrontation between Iran and Israel, NATO’s comprehensive cooperation with Israel, U.S. involvement in deceiving Iran as well as in military operations against it, and the cooperation of the International Atomic Energy Agency with Israel have demonstrated that the contradictions between Iran and the West are structural rather than tactical. This realization has, in turn, shifted Tehran’s understanding of deterrence from one based on diplomatic engagement to one grounded in hard power. In other words, political decision-makers in Tehran have concluded that managing tensions with the United States—contrary to earlier assumptions that negotiations, de-escalation, and problem-solving through political dialogue could yield results—can only be achieved through hard deterrent power capable of exerting pressure on and inflicting damage to U.S. interests.

Accordingly, Iran’s foreign policy in the near term will be heavily shaped by security considerations. This, in turn, will tilt the balance of influence in Iran’s overall policymaking more decisively toward military actors and increase their impact on foreign policy processes.

This security-oriented perspective will also cast a shadow over relations with Europe. Iran believes that Europe no longer possesses an independent will, distinct from that of the Zionist lobby and the prevailing decision-making center in Washington, and that in various dossiers it has failed to demonstrate the capacity to resist the will of the Zionist lobby and the United States. As a result, Tehran is likely to approach its dealings with Europe less with the aim of creating a clear horizon for constructive long-term cooperation and more with a narrow focus on resolving specific issues and preventing severe crises.

In other words, Iran’s foreign policy—much as has been observed over the past month—will in the coming months remain primarily focused on efforts to prevent major military and security crises, a dynamic that will also alter the domestic political weight and influence of different internal actors.

Domestic Politics

As the overall situation in the country has shifted toward security priorities, the political weight of security and military figures in domestic politics has naturally increased. It appears that the Supreme National Security Council has evolved from being merely a coordinating body among security institutions into a central coordinating institution across the entire structure of governance. Given that the Council’s secretary, Ali Larijani, is himself one of the key and influential figures in Iranian politics, he has gradually become a more prominent and consequential actor than the foreign minister, the interior minister, and even the president. In parallel, Ali Shamkhani and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf—who serve respectively as Secretary of the Defense Council and Speaker of the Majles—have gained significant political weight in the post–12-day war period. As a result, Masoud Pezeshkian has, to a considerable extent, come to operate under the shadow of this political triangle.

At the same time, the prevailing security environment within the country has rendered radical elements in both the reformist and conservative camps relatively inactive, while providing moderate figures with greater opportunities for influence. This trend had already begun with the formation of the Pezeshkian government. Although his administration is considered reformist, it has made use of a substantial number of conservative managers. In the months following the war, there has also been a noticeable decline in the activity of hardline elements. However, the approach of governing authorities toward hardliners differs between the two factions. While radical conservatives have largely been urged to remain silent without facing judicial proceedings, the reformist camp has, in recent days, witnessed the arrest of a significant number of its key figures. These arrests have generated notable criticism regarding the conduct of security forces under the country’s sensitive conditions, with some analysts arguing that such actions run counter to efforts aimed at maintaining calm. By contrast, analysts close to the judiciary and security institutions have framed these arrests as part of the government’s efforts to prevent politically provocative actions within the country.

The strengthening of the security and military camp in managing the country may, in the coming months, extend into the economic sphere as well. A substantial portion of Iran’s current political crises is rooted less in politics per se than in economic conditions and public livelihoods. Much of the economic distress has stemmed from factors such as the failure to repatriate foreign-currency earnings from exports, the inability of certain trusts to sell oil, the lack of cooperation by private banks with the Central Bank, and the noncompliance of some private companies and holding firms with the government’s currency policies. According to many experts, addressing these issues requires a security-oriented approach and the involvement of supervisory and security institutions. From this perspective, Iran’s economic challenges have ceased to be purely economic matters and have instead become instruments of security and political pressure exerted by the West against Tehran.

Leave a Reply