On Sunday, November 10, parliamentary elections were held in Spain for the second time this year. The parties elected in the first contest in April have been unable to agree on who should serve as President, leaving the government in a deadlock. As a result, new elections were called to end the stalemate. The new negotiations are taking place against a backdrop of serious economic, political and social uncertainty. On the economic front, the process continues to fall under the shadow of the 2008 financial crisis. On the political front, mass uncertainty has fomented a crisis in governance, while on the social front, ideological fractures continue to escalate.

These social fractures are especially notable in Catalonia, where there has been an upsurge in violence by separatist groups, particularly after the Spanish Supreme Court sentenced 12 leaders who had been involved in an illegal referendum held on October 1, 2017. Their prison sentences range from 9 to 13 years on charges of sedition and embezzlement, while others were fined for disobedience. Those involved have also been disqualified from running for office in the future. Some separatist leaders have fled to Switzerland or other countries.

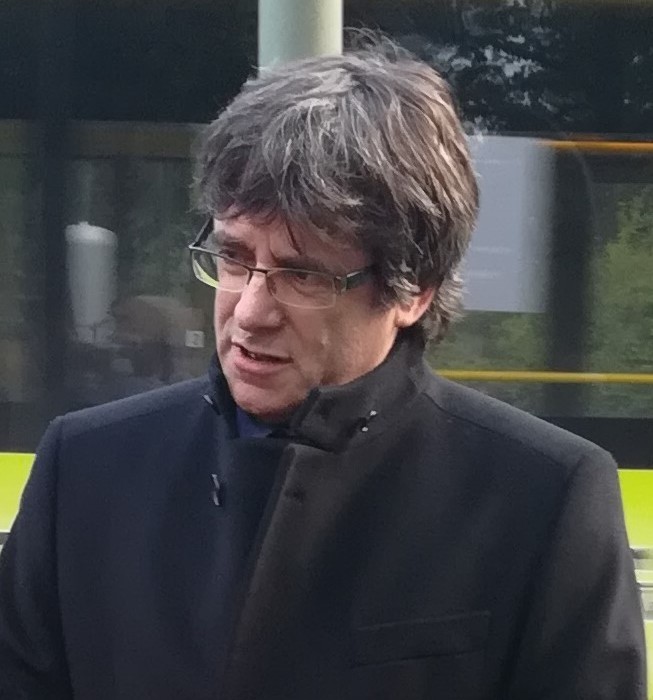

The most prominent figure to flee the country is the former regional president of Catalonia, Carles Puigdemont, who is in virtual exile from Spain pending criminal charges.

Wikipedia

June 2018: change and uncertainty

On June 1, 2018, the Congress of Deputies passed a motion of censure expelling then-President Mariano Rajoy of the Popular Party, appointing the Socialist Party’s Pedro Sánchez as the country’s new president. The surprise shift in Spanish politics at first seemed to bring some changes for the better… however, in reality, the situation has been worsening ever since, either due to President Sánchez’s ineffectiveness or as a result of his policies inspiring tension and unrest. Critical issues like unemployment have been eclipsed by the heavy emphasis in the mass media on the situation in Catalonia, as well as various distractions pushed by President Sanchez since he came into office.

One example is his proposed exhumation of Francisco Franco (who ruled Spain between 1939 to 1975) from the Valley of the Fallen. The push to remove Franco’s body created drama in the media that went on until October 2019, coinciding (by chance or coincidentally) with the sentencing of the separatist leaders.

VOX: has a fifth political force arrived?

Last April’s general election saw the right-oriented party Vox win 23 seats in the Congress of Deputies. The new party burst into Spanish politics after its political debut in the regional parliament of Andalusia, where it won 12 seats in the December 2018 elections. The mainstream media in Spain, with varying degrees of hyperbole, has accused Vox of being a “radical”, “far-right” and even a “fascist” party, attempting to stoke fear in society against them. All of this is taking place a context of multilevel fractures that are growing by the day. However, there is no basis to consider Vox a populist party like the ones emerging across Europe, as the party actually emerged from the neoliberal right of the Popular Party and is completely oriented toward the United States and NATO. It is worth mentioning that Vox’s burst in popularity has helped open up public debate on social issues where the left had formerly been nearly hegemonic.

¡VOX 3° FUERZA!#EspañaSiempre

???????????? pic.twitter.com/KJlaMdrzM3

— VOX ???????? (@vox_es) November 10, 2019

The November election campaign: boredom and distance

The social fatigue surrounding the Spanish government has been strongly felt through the recent electoral campaign, a fact which is evident given that the contest began without the usual large-scale inauguration spectacles. The electoral campaigns have been carried out without election posters appearing in every city or any of the other expectant fanfare… most seem to have not taken notice of the process at all.

The general perception is that parliament is to blame for being unable to come to agreement on a new government, and that these new elections will only result in more uncertainty and unnecessary expenditure.

However, the leftist party “Unidas Podemos” (United We Can) has seemingly worked the hardest, attempting to win back the portion of the electorate they lost after years of internal crisis and the discrediting of their leader, Pablo Iglesias. There was a massive scandal in the public after it was revealed he had moved into a mansion in Galapagar, one of the richest municipalities in the metropolitan area of Madrid, despite coming from one of Madrid’s most typical working-class neighbourhoods. His house is guarded 24/7 by the Guardia Civil (Police), despite that he had criticized such measures strongly and publicly in the past. Most critically, however, was the abandonment, expulsion or resignation of the party’s main leaders, particularly Íñigo Errejón, the “mastermind” of Podemos’s political strategy and close friend of Iglesias. Errejón formed his own party and launched himself into municipal politics during the elections in May 2019. His new party became an important political force both in the City Hall and in the regional parliament of Madrid.

???? "Estas elecciones han servido para que la derecha se refuerce y para que tengamos una extrema derecha de las más fuertes de Europa.

Se duerme peor con más de 50 diputados de la extrema derecha que con ministros y ministras de Unidas Podemos".

@Pablo_Iglesias_ ???? pic.twitter.com/mvy0NT6pap

— Podemos (@PODEMOS) November 10, 2019

In the wake of November 10: now what?

The most abrupt shift of the elections was the party “Ciudadanos” (Citizens) losing 47 seats, leaving them with a grand total of 10. Meanwhile, the “Popular Party” managed to take 22 new seats, while Vox took 28. Vox’s results were the biggest surprise of election night, as the pre-election polls had not indicated they would achieve anything close to these numbers. One survey conducted just ahead of the election by the Centre for Sociological research estimated that the party would end up with between 14 and 21 seats, but when the plosed closed, their total came to 52. At the same time, the polls indicated a slight boost for Unidas Podemos, but the party ended up dropping from 42 seats to 35. The same poll also predicted that the Socialist Party would go from 122 seats to somewhere between 133 and 150 seats: as it turned out, they actually lost two.

As an additional note on the post-electoral day, we have as a result in the party “Ciudadanos” the resignation of its leader, Albert Rivera after 13 years at the head of that party, due to the very bad results obtained. Likewise, on Monday, November 11th, Catalan separatist groups have tried to cut with barricades the border crossing-point of La Junquera, which is the busiest between Spain and France, and continue to call for more mobilizations that, like all the previous ones, only affect the workers and not the politicians in power. Let us remember that they are cuts on highways and airports, and not around the buildings of the political institutions both regional and national.

With the election results tallied, the following coalitions will likely be formed in order to produce a functioning government:

1) Firstly, there is the “left-wing coalition” headed by Socialist Party of Pedro Sánchez, the formation most likely to achieve an absolute majority (176 seats) in the Congress of Deputies. This coalition can likely count on the support of the Socialist Party (121), Unidas Podemos (35) and Errejón’s Más País (3) for a total of 158 seats. In order to achieve an absolute majority, they will need the support of at least two minority parties as well. While Ciudadanos is one possible candidate, they will also need the support of another separatist/nationalist party, such as the Basque Nationalist Party (7). In this scenario, the formation would end up with 175 seats, only 1 off the majority they require, leaving them to rely on the support of some other regional party, of which there are 5 options: Canarias (2), Navarra (2), Galicia (1), Cantabria (1) or Teruel (1). However, in order for parliament to nominate someone for the presidential post, only a simple majority is required, which means that Sánchez’s Socialist Party will only need more votes in favour of their proposed candidate than against; the hope here is that some opposition groups with simply abstain. At the same time, a debate will have to take place within this left-wing coalition about how to obtain support from the Catalan separatist parties boast some 23 seats in total. This will likely be a heavy debate given the price they might have to pay in order to secure support given how heated the question of territorial division has gotten, the strength of the separatist impulse and the recent high-profile sentencing of the movement’s leaders.

El voto de hoy decidirá la España de mañana. La democracia nos une como país, nos hace mejores. Participemos, expresemos nuestra voluntad con nuestro voto, hagamos más fuerte la democracia.#EleccionesGenerales10N pic.twitter.com/ojRX9aLrA9

— Pedro Sánchez (@sanchezcastejon) November 10, 2019

2) The second likely formation is a “right-wing coalition” headed by the Popular Party of Pablo Casado (88 seats), followed by Santiago Abascal and Vox (52), where Ciudadanos (10) could potentially serve as a third. At the moment it is unclear what the future of the group’s leadership will be, starting with questions around Albert Rivera. Together, the three parties would have some 150 seats, meaning they would still need 26 more to obtain an absolute majority and propose a presidential appointee. If they were able to secure the votes of the nonseparatist regional parties, they could swing 6 more seats from Coalición Canaria (2), Navarra Suma (2), Partido Regionalista de Cantabria (1), ¡Teruel Existe! (1). Even in a best case scenario, the maximum number of seats that they could gather would be 156.

Whither Spain?

The majority of Spaniards are now asking themselves where their country is headed, as no one knows whether an agreement will be reached or a President appointed. Many are also asking what price Sánchez is willing to pay in order to secure the support of nationalist/separatist elements. Over the last 40 years of democracy in Spain, these nationalist/separatist parties from the Basque and Catalan regions have been the key to forming a government when one of the large national parties failed to win an absolute majority in Congress. In other words, both the Socialist Party and the Popular Party have relied on their support in order to appoint a government. The conditions of earning these groups’ favor have included granting further autonomy to the two regions, that is, assisting them in their slow-motion transformation into semi-States within Spain.

Currently, it is the separatist challenge in Catalonia (as well as broader territorial debates) which dominate the public agenda, remaining the focus of attention for politicians and the media.

However, it is important to note that the separatist challenge itself emerged from the liberal-right party “Convergència i Unió” (CIU) (Convergence and Union) in 2010. At that time, the party began to talk openly about independence, blaming the poor economic situation resulting from the 2008 global financial crisis on the Spanish government. From that moment on, the liberal-nationalist right took a separatist turn, fuelling hatred and territorial tensions: they began to blame Spain for just about everything. However, the regional government of Catalonia, under the leadership of CIU, itself enacted social welfare cuts, especially when it came to Education and Healthcare. Nonetheless, they blamed the government for the consequences of their actions and began to clamor for “independence” even more aggressively. Essentially, they covered up their own unpopular liberal policies with calls for independence… however, this strategy eventually did lead to a rupture in the party, resulting in it falling apart and being replaced by “Esquerra Republicana” (ERC) (Republican Left-wing), which is now the nationalist/separatist party with the highest number of votes.

This party is now vying for leadership of the separatists against former president Carles Puigdemont and his party, JXCAT (which is essentially the new incarnation of CIU).

It is difficult to imagine how the territorial crisis will be resolved or how a new government will ever be appointed. At the same time, it is clear that Spain’s current politicians are not even trying to find a solution, hoping to draw out these problems as long as possible and thus maintain their political circus. These politicians are only out to protect their private interests, unbothered by the fact that their misleading spectacle is resulting in massive social unrest and increasing confrontation. These internal debates, the fruit of politicians who act more like parasites than leaders, have resulted in Spain’s weakness on the world stage. Geopolitically, we are a crucial point of passage, we could easily be a pivot point of global importance, yet, instead, we are systematically sunk in debilitating internal contradiction. Coincidence? I very much doubt it. Neither our European “allies” (especially from the United Kingdom, France and Germany) nor the North Americans want Spain to play an important role in the international arena, fearing that achieving importance would coincide with the development of an autonomous policy and orientation. In short: Spain must not be allowed to play a role as a geopolitical pivot, it must remain a weak and wounded country, a casualty of the post-modern West.

The only thing which seems certain now is that the government will have to agree on some kind of pact in order to resolve the situation temporarily, because a third election within a 6 month period would undoubtedly prove intolerable for a society already fed up with the uncertainty and corruption of its politicians. Social unrest and disdain for mainstream politicians is seemingly the only thing on the rise in Spain today.

Leave a Reply