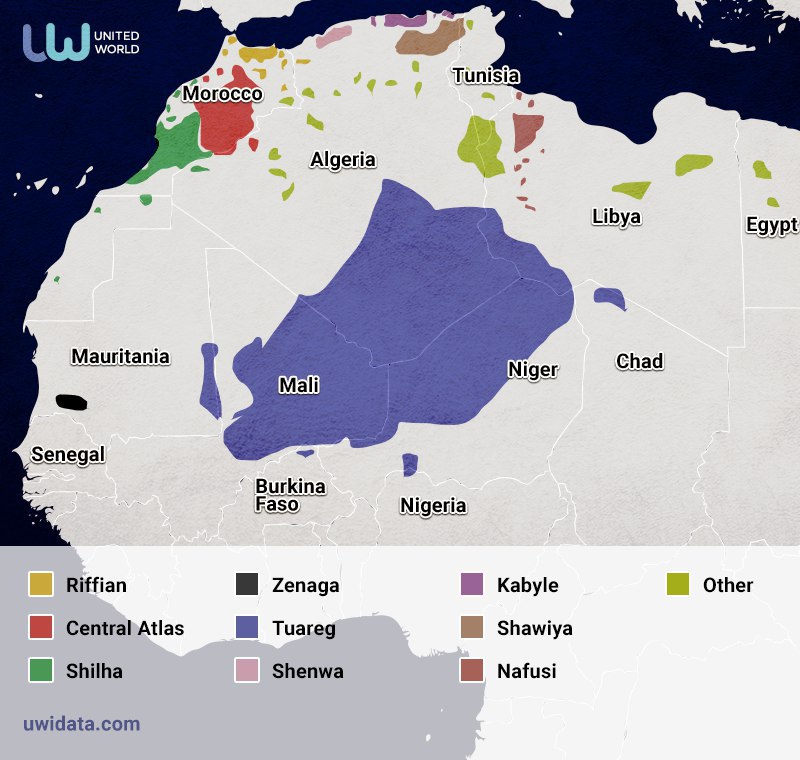

The Berbers are the indigenous people of North and West Africa, the ethnic substrate on which Arabization was later superimposed. Despite the fact that Arabs make up the majority, a significant part of the population from Libya to Mauritania has Berber roots. The size of the Berber (Amazigh) population is estimated to be between 30 and 50 million people, making them one of the largest nations in the world without their own state.

In some countries, the Berbers constitute a consolidated community that makes them important geopolitical actors. The question is whether the Berbers play a unified role in the geopolitics of Africa, or whether disagreements between individual tribes and communities prevent them from acting as a singular force.

Libya: Ibadites and the GNA

To begin with, let’s consider what role the Berber groups play in armed conflicts in North African territory.

Libya, where up to 10% of the country’s population (about 600,000 people) are Berbers, is engulfed in a civil war. In the north, the Berbers live in the area around the city of Zuwara (named after a Berber tribe and in the Nafusa mountains. A feature of this part of the Libyan Amazigh community is its commitment to Ibadism, a branch of Islam historically associated with the Kharijit movement. During the reign of Muammar Gaddafi, the Berber- Ibadite identity was suppressed in favor of Arab identity. The local population took an active part in the uprising of 2011, opposing Libyan Jamahiriya and consequently achieved a degree of autonomy.

The terrain in the Nafusa mountains makes it possible to maintain relative isolation from the outside world. In the current Libyan civil war, its inhabitants have grown closer to the Government of National Accord in Tripoli (GNA). One reason for this was that this year, Libya’s Supreme Fatwa Committee (which is close to the Libyan National Army Khalifa Haftar) issued a fatwa which named the members of by Libyan Ibadi community “infidels without dignity”. One possible reason for this decision was the influence of Salafi clerics associated with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Salaf-Madhalites groups enjoy great influence within LNA.

The Government of Fayez Sarraj opposed the fatwa. However, there is information that there have been clashes between the Berbers and GNA forces. The Madkhali Special Deterrence Force (Rada) which is loyal to the GAN, is claiming control of the territory from Tripoli to Zuwara.

However, these frictions are likely also economic in nature. Zuwara is located near the border with Tunisia and local leaders straddle smuggling operations. At the same time, among the intellectuals speaking on behalf of the Libyan Berbers, calls are heard for autonomy within Libya and some statements even suggest that the Kurdish experience in Syria has been a source of inspiration. According to Seham Bentalab, an elected ASC member, the Libyan Berbers have achieved “de facto independence.”

One of their most prominent leaders is Libyan dissident and former World Amazigh Congress president Fathi Ben Khalifa, who established the Lybo Party in 2017.

In 2017, the political body of the Libyan Berbers, The Amazigh Supreme Council (ASC), declared the Libyan National Army a “terrorist” force.

The organization also calls the army of Khalifa Haftar a “threat” to Libyan Amazighs, accusing the government in eastern Libya of repression on religious and ethnic grounds.

Significantly, after being united by the ASC, the Amazigh people boycotted the 2014 Elections and are therefore not represented in the House of Representatives.

Libyian Fezzan: the Tuareg factor

In southern Libya, another group of Berber-speaking tribes traditionally lives in Fezzan, the nomadic Tuaregs. It is significant that, unlike the Berbers of the north-west, during the 2011 war, a significant part of Libyan Tuaregs sided with the loyalists. The Tuaregs are Sunni Muslims. If the Berbers of the north accuse the Gaddafi regime of striving to erase their identity, then the Tuareg nomads, on the contrary, became the guardians of the old regime. Special forces were formed from among them.

In 2019, the former Libyan Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Ibrahim Dabbashi, published documents according to which in 2009 the Libyan government granted citizenship to 1722 Malian Tuareg fighters and 83 officers who were supposed to serve in the special forces battalion under the command of General Tuareg Ali Kanna.

Ali Kanna returned to Fezzan from Niger in 2013 and began to assemble an army of Qaddafi-loyalists from local Tuaregs and those from neighboring Mali, Niger and Chad. At the same time, Ali Kanna opposes the Libyan National Army of General Haftar, where most of the officers of Gaddafi’s army serve.

In the past year, Fayez Sarraj appointed general Ali Kanna as the military commander of the Sebha region. At the same time, Kana himself at different periods demonstrated his readiness to communicate with the LNA and the GNA, advocating that the Tuareg of southern Libya should not be touched.

Libyan Tuaregs control the illegal transportation of oil from fields in the south to neighboring African countries. Complicated and conflicting relations connect the Tuareg of Fezzan with the Arabs and the Nilo-Saharan people of the Tubu, who live in southern Libya and in the Republic of Chad.

At the same time, both Tuareg and Tuba have a negative attitude toward the prospect of establishing LNA control over the processes in their communities which are closely tied to related tribes in neighboring countries. One serious problem is the fact that a significant part of the Libyan Tuareg are perceived in Tripoli and Tobruk as “foreigners”. Some came from other African countries during the time of Gaddafi with their families, those who served the government were often promised citizenship… not to mention that the borders established by European colonialists were not taken into account by the nomads as a significant factor.

Ali Kana is considered close to Hussein Al-Koni, the former Libyan Jamahiriya ambassador to Niger. Previously, he headed the Supreme Council of Tuaregs in Libya.

In 2018, a new body was created which claimed to speak on behalf of the Tuaregs – the Supreme Tuareg Social Council led by Moulay Gnedi. He, in turn, is closer to the Libyan National Army of General Haftar.

In February 2019, his mediation allowed for the transfer of LNA control over the largest oil field in Libya – Sharara. Until this time, the field was controlled largely by the Tuareg 30th Brigade of the Petroleum Facilities Guard.

During the Lybian Civil war, the Border Guards Brigade 315, an Islamist militia led by Tuareg Salafist scholar and former Ansar al-Din deputy commander Ahmad Omar al-Ansari, played a crucial role.

Tuaregs and Islamists

Iyad ag Ghali is a prominent figure in Islamist circles. In the past he was a fighter for Tuareg self-determination in Mali and one of the founders of Popular Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MPLA), then the Popular Movement of Azawad (MPA). He launched the Tuareg Rebellion of 1990-1996 but eventually reconciled with the government. However, he later became the leader of the radical Islamists in the region. The transformation took place after he was in Saudi Arabia from 2007 to 2010, where he served as part of the diplomatic corps of Mali. With his help, the Islamists seized the initiative in the Tuareg uprising in Mali from the newly created National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in 2012.

At the end of August 2011, several hundred Mali Toaregs from the Libyan Maghawir Brigade led by General Ali Kana deserted and returned to Mali, becoming the backbone of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA).

After the defeat of the uprising in Mali, some of these Tuaregs returned to Libya. It is significant that Iyad ag Ghali was also a former member of the Islamic Legion of Muammar Gaddafi.

Wikipedia

In March 2017, terrorist groups loyal to Al-Qaeda of North Africa (Ansar al-Din, al-Mourabitoun, the Macina Liberation Front, and the Saharan branch of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghre (AQI) united in Jama’ at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (JNIM), operating in Tuareg populated regions of Algeria, Niger, and Mali). Iyad ag Ghali eventually became the head of the organization.

On February 11, 2020, the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, confirmed that efforts were being made to engage in dialogue with Ag Ghali.

The prominent North African Jihadist leader Algerian Mokhtar Belmokhtar (Al- Mourabitoun, AQIM) used a base in Fezzan to attack Algeria’s In Amenas gas plant in 2013. He then married four local Berber and Tuareg women to establish strong ties to the region.

Separatism in Mali and Niger

The Tuareg factor in Mali manifests not only in Islamist activities (there are other ethnic groups also active, such as Fulani), but also in continuing separatist activity. In 2015, the rebels and the Government of Mali concluded agreements to normalize the situation in the country with the mediation of France.

Formed in 2014, the Coordination of Azawad Movements, which included Arab and Tuareg movements (including the remnants of MLNA ), still controls part of the territories in the North, such as the city of Kidal. Today, they support Mali separatism and seek special status for Azawad. De facto, they are accused of having links with terrorists and separatism. The military and diplomatic efforts of France have not solved the problem of Tuareg separatism and Islamism in Mali.

France’s allies in the fight against ISIS in Mali (the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, EIGS) are two Tuareg paramilitary organizations: The Movement for the Salvation of Azawad of Moussa Ag Acharatoumane and Assalat Ag Habi (which has around 3000 fighters) and the pro-government Touareg militia The Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies (GATA) (with around 1000 fighters) led by General El Hadj Ag Gamou (a former officer in Gaddafi’s army and a Tuareg rebel). Since September 4, 2019 he has served as Inspector general of the Malian armies and services.

The situation is complicated by both the personal enmity of the leaders and contradictions within the tribes, some of which traditionally had a privileged status (for example, the Ifoghas of Ag Ghali), while others are considered vassals of the former (for example, the Imghad of El Hadj Ag Gamou).

Another country where Tuareg military groups were active in the recent past is Niger.

It is significant that since the 1960s, it was in Mali and Niger where the Tuaregs periodically rebelled against the government, areas where power, since the declaration of independence from France, has been concentrated in the hands of black settled peoples. This is largely due to the reluctance of local elites to integrate the Tuaregs, instead imposing an alien identity on them (in Mali it is a historical narrative that raises the country’s history to the medieval empire of Mali) or marginalizing Tuareg nomads.

Wikimedia Commons

In Niger, the last Tuareg uprising took place in 2007-2009 (at the same time, the Tuareg rebelled in neighboring Mali). There are indicators that in the case of Niger, the Tuareg was supported by other nomadic peoples of the north such as the Fulbe (Fulani) and Tubu. The main role in the uprising was played by the Movement of Nigeriens for Justice (MNJ). This organization was involved in the abductions of Chinese and French specialists working in uranium mining enterprises. The Tuaregs and their allies in Niger are seeking their share of the exploitation of the natural resources of the area.

In 2011, the former leader of this organization, Aghali Alambo, helped Saïf al-Islam Gaddafi and his brother Saadi to flee to Niger. In Niger, among the local Tuaregs, senior Tuaregs from the army of Gaddafi, including Ali Kan, found shelter.

In Niger, unlike Mali, separatist sentiments among the Tuaregs are not so strong. They have become associated with the concessions made when peace was concluded with the mediation of Muhammad Gaddafi. At the same time, ISIS terrorists are operating in vital regions for the country in terms of resources. Last year, 7 traditional Tuareg leaders became their victims.

On the other hand, Mali’s specificity was shown in the fact that during the uprising of 2012, the Tuaregs first began to demand not only autonomy in the north of the country, but also their own national state (Free Azawad), which is hardly compatible with the specifics of the nomadic Tuareg society. However, the fact that some of the tribes supported the Islamists and some supported the current Mali government demonstrates that the ideas of self-determination and the creation of a secular national state in this environment are not particularly strong.

Conclusions

In other major military conflicts in North Africa, the Berber factor does not manifest itself explicitly. The Indigenous population of Western Sahara in Morocco are sometimes called the “southern Berber”, but Sahrawis adhere to Arab identity. Polisario, which is fighting for independence from Morocco, advocated the establishment of a state called the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic and adheres to Pan-Arabism. In 2016, Polisario militants killed young Berber activist Omar Khaleq in the Western Sahara.

Nevertheless, in the Sahrawis culture, distinct Berber traits are visible, especially in regard to the high status of women.

In general, it is worth noting that the Amazigh factor and Tuareg factors are important in military conflicts in North Africa. In Libya, Mali and Niger, one can clearly distinguish military-political actors who rely on the Berbers.

At the same time, wherever we turn, the Libyan conflict remains of key importance. Gaddafi’s government used repressive policies to freeze autonomist tendencies in the Berber areas in northern Libya. In the south and in the regions of the Sahel, on the contrary, it acted as a point of attraction for the Tuaregs, although Gadaffi used them to strengthen his influence in the wider region of Sahel.

In the case of the Ibadites of northern Libya, the collapse of the Libyan state allowed them to strengthen their autonomy, which they are ready to defend. However, this factor did not go beyond Libyan territory. On the contrary, in the south, the fall of the government, the deterioration of the position of the Tuaregs, the liberation of large masses of weapons and well-trained people in Gaddafi’s army gave an impetus to both the increased activity of the Islamists and the armed activity of the separatists.

Tuareg communities, which share a common identity but are nonetheless second-class citizens in all of the countries where they are found, may become a breeding ground for extremists of all stripes. Despite their many differences, as is the case with Kurds in the Middle East, it cannot be ruled out that they will be exploited by forces external to the region in order to destabilize it.

Leave a Reply