Visiting the World Expo Paris in 1900, The Shah of Iran Muzaffar ad-Din was so impressed by a screening of a film he had watched in a pavilion, that he immediately bought a camera and thus took the first step towards the art in his country. The first themed movie was shot in 1929 while national cinema began to take shape in the 1950. Iranian cinema, which had found its identity during the era of Shah Reza Pahlavi, was the first step toward today’s Fajr Film Festival which was eventually open to the outside world with the Tehran International Cinema Festival in 1972, and continues to this day despite strict censorship laws and interestingly, with the support of the government which plays an important role.

During the late 1960s and 1970s Turkish and Iranian filmmakers cooperated a great deal with productive results for cinema for the national cinema in both countries. This period ended due to political events in the both countries leaving no permanent traces, despite that artists such as Turkan Soray, Zeynep Milleroglu, Filiz Akin, Cuneyt Arkin and Kartal Tibet had travelled to Iran and played important roles in films, while Iranian stars such as Naglaa Fathi, Nasser Malek and Cihangir Gaffari appeared in Turkish films.

Iranian Cinema, which experienced a serious recession period after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, began re-appearing at the international film festivals in the mid-1980s and started to shine. The Iranian national spirit had begun to express itself on the screen in its thousands of years of cultural accumulation, its folk tales, poetry and its songs. A very colorful flower had bloomed, and in a way that was never seen before.

Reflections of daily life in society

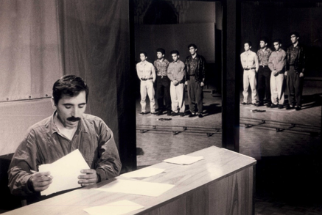

Sitting at a table in the middle of a large hall, a man speaks with hundreds of men and women who come and sit before him. Meanwhile, two separate cameras record the conversations.

A selection of the conversations is made for a film in honor of the 100th anniversary of the art of cinema. An announcement was made for trial shoots in the newspapers, to which 5,000 people responded. When the director speaks to the candidates one after another, Iranian society starts to appear as a microcosm. Workers, intellectuals, students and women explain why they want to take part in this film, their expectations and their motivations. While the director tries to bring out the candidate’s character and the acting talent, the audience starts to dive deep into Iranian society, facing its reactions and controversies, encountering the daily reflections of the entire culture.

The result is a cinematic journey where reality is intertwined with fiction, simple but extremely impressive and enjoyable. One girl was asked to cry for the role, then she was told that she could not be in the film when she could not do it, the girl had started crying out of sadness in response, and was later selected for the movie. Everything was real from start to finish.

Poetry written with a camera

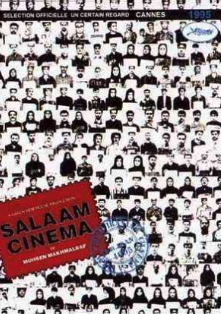

This finished film was entitled Hello Cinema (Selam Sinema), and it was directed by Mohsin Makhmalbaf. It is a wonderful summary of Iranian cinema of the last 25 years, where the audience experiences the confusion of whether the movie is a typical documentary or a well garnished fiction. Makhmalbaf, one of the pioneers of Iranian cinema who achieved international fame during the mid-1990s, has gone back and forth between documentary and the fiction, obscuring the areas where life is involved in cinema and the cinema involved in life. Makhmalbaf responds, on behalf of the new generation of Iranian cinema, to the immortal poet Forough Farrokhzad, saying: “Why the father should be alone/ should be asleep”; the voice of Yushij “And on the road / the man who plays the caval / is walking/ in his cloudy world,” has echoed once again, relying on the the poetic accumulation that he and almost everyone from his generation inherited, writing this poetry with his camera. Cinema is the poetry of the East today, something which can best be understood by watching at the Iranian films.

Never underestimate

Iranian cinema, which nullifies accusations that Iran is merely a “totalitarian, anti-democratic country” where “arts, especially the cinema, are unable to develop properly.” The lesson of the stories in the film is that one should never underestimate anything when it comes to life and human beings. Characters are depicted as finding happiness in small things, but always with an interesting and creative element of roleplaying that blurs the line between acting and reality. Children, women, young adults, intellectuals, peasants, lovers, smugglers and traders all appear, while Tehran, the slums, the borderlands, and even small mountain villages are filmed with a mature cinema language that surprises and charms. Every scene is a cinematic conquest pivoting from reality while rejecting the domination of the image as such.

“However the world did not surprise us”

In his book “Iranian Cinema / Past, Present and Future”(Agora Publishing, Translation: Baris Aladag-Begum Kovulmaz, 2004), Hamid Dabaşi writes: “Iranian cinema has surprised the world, as they had concluded that our society had closed off after Islamic Revolution. The restrictive circumstances did not fit well with liberal perspectives in regard to our country. That is why the whole world was so surprised. However, the world did not surprise us back. We watched, absorbed and heard countless charming and loud voices; Then we reflected these back from our point of view.” Dabaşi highlights that directors in Iran today have understood that “everything is possible in cinema” even without the advanced technology, a million dollar budget and computer effects. These directors have proven themselves to be successors of the modernist Persian poets of the 1950s-1970s. “Our culture, which is rather literal at its core, has taken a visual turn which has made our cinema a powerful art… Cinema has revealed the hopes that we hide nationally,” Dabaşi continues.

Intellect and genius

In this extraordinary transformation, or perhaps, accurately, the striking cultural-artistic continuation of the past, directors such as Mokhsin Makhmalbaf, Abbas Kiarostemi, Rakhshan Banietemad, Amir Naderi, Jafar Panahi, Bahram Beyzai, Bahman Farmanara, Bahman Ghobadi, Daryush Mehrjui, Hassan Yektapanah, Samira Makhmalbaf, Majid Majidi and Asghar Farhadi stand out as exemplars.

Films like; May Lady, A Time for Drunken Horses, Taste of Cherry, Smell of Camphor Scent of Jasmine, The Wind Will Carry Us, Blackboards, Maybe Some Other Time, Where’s the Friend’s Home, Silence Between Two Thoughts, Two-Legged Horse, Friday, Offside, Children of Heaven, A Separation all make the list of “unforgettable” Iranian films.

Iranian directors and films, which have won numerous awards at some of the most respected events related to world cinema, including some internationally renowned film festivals such as Cannes, Venice, Montreal and Berlin, helped reinvent cinema in the ’90s as Italian neo-Realism had after World War II. An original, innovative and colorful new cinema had come onto the scene from Iran. This status was achieved despite the struggle with censorship, something which was never used as an excuse. While the relationship between film and the state in Iran is one of the most interesting and lucid examples of such phenomena (alongside China), some Iranian propaganda films were also produced with no place for bad or negative characters, and no room for criticism… In the broader scope of Iranian cinema, however, we have seen romance, genius and critiques of the regime.

The work of Iranian filmmakers is also supported by a state-sponsored cinema center (Farabi Cinema Foundation) in 1983 and the International Fajr Film Festival, has surpassed its 38th year, and continued to provide calm, patience and meaning to the world for many years after.

A Regional Cinema Cooperation

This year at the 70th Berlin Film Festival, Mohammad Rasoulof (who had won the Golden Bear for his film “There Is No Evil” like his countryman Jafar Panahi five years ago, and, again like Panahi, was unable to attend the award ceremony due to problems with the Iranian government) shows that the art of cinema continues to be the one of Iran’s most important exports.

In Iran, directors of Turkish origin who speak Turkish and live in Tabriz and Ardabil have successfully blended Turkish and Iranian cultures. Two years ago, an exhibition entitled “Film Days from Iranian Cinema in Turkish” was held in Istanbul during, providing a rich matinee of four feature films, four documentaries and 13 short films.

It is beautiful to imagine how things would have changed for the better if these countries were able to utilize their decades of cooperation in order to begin fostering the cinematic arts in Iraq and Syria.

Leave a Reply