By Islam Farag, Cairo / Egypt

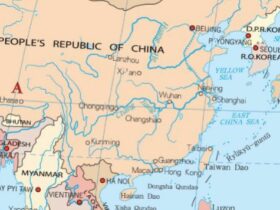

The visit of the head of Egyptian intelligence, General Abbas Kamel, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Badr Abdel Aati, to Eritrea was a very significant message to all eyes monitoring the Horn of Africa region.

The visit by the two Egyptian officials appeared to be a warning to the Ethiopian government, which has announced that it will go ahead with implementing a memorandum of understanding signed with the Somaliland government.

The memorandum, signed in January, stipulates the leasing of 20 kilometers of Somaliland’s coastline on the Gulf of Aden to Ethiopia for 50 years.

Somali rejection

Following the signing of the memorandum, relations between Addis Ababa and Mogadishu became tense, as the latter does not accept or recognize the independence of Somaliland from its territory. In fact, the regional government is a separatist government that does not enjoy any international recognition at all. Ethiopia, a landlocked country, is exploiting this situation through a trade-off between recognizing the breakaway government in exchange for a port and naval base overlooking the Gulf of Aden. If this happens, Addis Ababa will be the first capital in the world to recognize the breakaway region since it unilaterally declared independence in 1991.

While Somalia rejects this memorandum as a threat to the unity and territorial integrity of the country by strengthening the power of a separatist region, Egypt is completely suspicious of Ethiopian behavior and believes that Addis Ababa intends to obtain a sea outlet in the Gulf of Aden, threatening the safety of navigation in it and in the Red Sea, which represents a strategic waterway that Cairo cannot afford to tamper with, especially since it represents the main gateway for the movement of ships coming to the Suez Canal, a waterway of geopolitical and economic importance to the country.

Egypt cannot view Ethiopia’s attempt to gain a sea outlet on the Gulf of Aden in isolation from its moves to change international borders, whether through its military incursions into the Somali region of Berbera, or through signing agreements with unauthorized parties with the aim of imposing a fait accompli in this region.

At the same time, the Ethiopian attempt coincides with a major dispute between Cairo and Addis Ababa over the Renaissance Dam that the latter is building on the Nile River, Egypt’s only water artery, without paying attention to Egypt’s demands for the necessity of signing a binding legal agreement that regulates the operation of the dam in a way that prevents harm to Egypt’s historical share of water and prevents it from being used as a political card to blackmail Cairo by making it thirsty, especially in years of drought.

Eritrean concerns

While Cairo and Mogadishu reject Ethiopian moves to own a port on the Red Sea, Eritrea feels the same threat.

Eritrea fought a long war of independence against Ethiopia from 1961 to 1991. Years later, the two sides went to war over a border dispute, lasting from 1998 to 2000. Despite the end of the war, relations between the two countries remained tense and extremely hostile, until Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took power in 2018. In the Saudi city of Jeddah, the two sides signed a historic peace agreement to end the hostility between the two countries.

We all know that peace agreements do not change the calculations of history and the motives behind its movement. From this standpoint, peace between Asmara and Addis Ababa cannot prevent president Isaias Afwerki from being cautious. Eritrea realizes that the peace agreement concluded with its historical enemy was only tactical, by virtue of which Ethiopia rearranges its cards and builds its strength in preparation for achieving its expansionist dreams. The first goal of those dreams will be Eritrea itself, which was part of the ancient Ethiopian empire.

Winning a port on the Red Sea will not be a big step towards achieving the Ethiopian dream, but it will tamper with stable borders and rules that have gained acceptance in the Horn of Africa region.

The Horn of Africa region in general is made up of conflicting and competing nationalities, some of which cross borders. Any attempt to change borders or manipulate the shares of influence or stable gains of any of its components will, at the very least, explode the region.

Triple compatibility

Therefore, it was natural for the will of the three capitals, Cairo, Mogadishu and Asmara, to converge on security and strategic coordination in this issue and prevent any attempt to tamper with the security of the region and threaten the capabilities of its peoples.

Egypt signed a joint military cooperation agreement with Somalia and sought to participate in the African Union peacekeeping mission, as part of what Cairo sees as its right to protect its national security and its duty to defend the sovereignty of a friendly Arab state with which it has strong historical relations.

As for Eritrea, which suffers from international isolation and is concerned about Addis Ababa’s tendencies that threaten regional stability, it appears more positive in dealing with the Egyptian positions.

Ethiopian movements

While the Ethiopian position faces rejection from the three countries, Addis Ababa has sought to activate its regional movements, in an attempt to gain new supporters for its ambitions in confronting the three capitals.

Earlier this month, Ethiopian Chief of Staff Berhanu Jula visited Morocco. During the visit, the two countries agreed to enhance military cooperation. More importantly, there are leaks about negotiations between the two countries to enhance strategic partnerships between the two parties in exchange for Addis Ababa withdrawing its recognition of the Polisario Front, a liberation movement seeking the independence of Western Sahara from what it sees as Moroccan colonialism.

Ethiopia first recognized the Polisario Front in 1979 and remained one of its most important supporters before the level of support slowed in the last decade, which witnessed notable developments in the level of Moroccan-Ethiopian bilateral relations.

Some believe that Morocco is getting closer to Addis Ababa to spite Cairo, which is still committed to not recognizing the Front. This may indeed be the Moroccan position in light of the vague Egyptian position on this issue, which has emerged in several positions.

The most prominent of these positions was when an Egyptian military delegation participated alongside a Polisario delegation in “the Command Center of the North African Regional Capability” exercise, which was hosted by Algeria last year.

Also 10 years ago, an Egyptian media delegation visited the Tindouf camps in Algeria, which house Sahrawi refugees, and was followed by hosting the former leader of the Front, Mohamed Abdelaziz, in several well-known newspapers and magazines in Egypt.

As part of Addis Ababa’s campaign to gain new supporters in the face of the “Egypt-Somalia-Eritrea” tripartite position, Ethiopian Defense Minister Aisha Mohamed Musa visited the UAE and met with the UAE Minister of State for Defense Affairs Mohammed bin Mubarak bin Fadhel Al Mazrouei, to discuss enhancing military and defense cooperation between the two countries.

The visit came a few days after Egypt delivered military aid to Somalia on August 28, the first in more than four decades, based on a military cooperation protocol between Cairo and Mogadishu that was signed in last August.

Some may think that there is unjustified intransigence against a legitimate Ethiopian ambition to obtain a sea outlet, but the truth is completely different.

Djibouti offer

Djibouti has offered the Ethiopian government full control of the port of Tajoura in the north of the country, in a bid to defuse tensions in the region. By making this offer, Djibouti avoids being put in a position where it would be forced to side with one side in the conflict.

At the same time, it wants to maintain the interdependence of its economy with that of Ethiopia. Since the Ethiopian-Eritrean war, Djibouti has become the seaport for 95% of the Ethiopian market’s imports and exports. The fees it collects on operations carried out on behalf of Addis Ababa constitute one of the largest revenues for its government.

Despite the Djibouti offer, Ethiopia has refrained from commenting on it, although it serves its commercial objectives. According to observers, Ethiopia’s real intention is its desire to establish a naval force whose reasons and motives cannot be understood for a landlocked country except for its desire of regional expansion at the expense of its neighbors.

On the other hand, Addis Ababa showed no interest in Egyptian ideas that enhance cooperation between the Nile Basin countries, most notably the shipping line project linking Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea, which allows for a sea outlet for landlocked African countries.

The Egyptian proposal was one of the ideas put forward by Cairo to transform the Nile River into a tool for enhancing cooperation to achieve gains for all, instead of the mentality of conflict and imposing a fait accompli regarding the river, which Ethiopia is adopting.

Escalation in the Horn of Africa

Despite Egypt’s flexibility in agreeing to the construction of the Ethiopian Dam on condition that an agreement is reached to operate and manage the dam and the rules governing filling in drought years, Addis Ababa wasted time procrastinating and maneuvering until it reached the final stages of building its water project.

Although the recent Egyptian moves in Somalia represent an embodiment of the agreements concluded with Mogadishu, and some of them represent legal and required participation within the African Union Mission to Maintain Stabilization in Somalia, the Ethiopian reaction seemed very tense.

The Ethiopian Foreign Ministry issued a statement attacking the mission, and alluding to Egyptian participation as destabilizing the region and leading it into unknown position.

At the same time, there were reports that Ethiopian forces had taken control of Somali airports in order to prevent the arrival of planes carrying Egyptian troops to participate in the African mission early next year.

Cairo is today deeply frustrated by the failure of its 10-year negotiations with the Ethiopian government. It also feels that it was overly optimistic and over-expected about the possibility of reaching negotiated solutions that would guarantee development for all.

Therefore, observers interpret the recent Egyptian moves as an attempt to encircle Ethiopia with the aim of pressuring it to sign an acceptable agreement that meets Egyptian demands.

At the same time, they see the Ethiopian escalation as an attempt to avoid Egyptian pressure and get away with the dam project without any obligations towards the downstream countries, Egypt and Sudan, so that it can be used in the future as a blackmail card or even force them to redistribute the river water shares, and then force Cairo later to buy the water. These are malicious intentions that mean nothing but declaring the death of the oldest central state in history.

Dam crisis

This previous presentation attempted to detail the complexities that shape the features of the crisis in the Horn of Africa, which is on the verge of a resounding explosion that the international community will not tolerate. But defusing this fuse is possible if all parties exercise wisdom and choose a win-win solution to the Renaissance Dam crisis. They will not be able to agree on this path without the intervention of forces and organizations that enjoy a great deal of trust.

The two main parties, Egypt and Ethiopia, tried to resort to the Security Council and the United Nations, but this was to no avail. The United States intervened diplomatically, but its reputation as a biased country that manipulates crises to serve its own interests, wasted a historic opportunity to use its influence to convince the two parties to a just solution that would have preserved the balance of power in the Horn of Africa and prevented its explosion. The African Union also failed to provide anything that would entice any seriousness in dealing with it.

Opportunity and test

But history offers us both an opportunity and a test. The opportunity is to save the Horn of Africa and its people from becoming a new arena for conflict, even though the differences between its parties are solvable. The test is for the BRICS group, which has agreed to expand its membership by including Egypt and Ethiopia.

The dispute between the two countries over the Renaissance Dam represents a valuable opportunity for the organization to prove its worth and ability to influence global affairs.

Ethiopia clings to its full right to fill and operate the dam as a sovereign right, while Cairo sees the failure to reach clear rules for its operation, management and filling as an inherent right for it as a downstream country that has historical rights to the Nile water through several international and bilateral agreements since 1902, some of which were signed by national and independent Ethiopian regimes.

Egypt is not alone in facing the threats posed by the construction of the dam. Sudan also faces risks to its agricultural sector, but the collapse of its internal situation following the outbreak of the conflict between its army and the Rapid Support Forces has left Cairo alone in the political confrontation over the dam.

It can be said quite clearly that the two countries have succeeded in recent years in reaching an agreement on many points of disagreement, but they are still unable to reach a legal agreement due to the disagreement over the release of water during drought periods.

The biggest obstacle to a final solution is mistrust, including concerns in Cairo that Ethiopia wants unilateral control over the flow of the Nile. The dispute escalated earlier this year when then-Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry warned that all options were open to resolve the dispute, hinting that military action remained a possibility. The dispute has deepened as Addis Ababa says the dam is nearing completion.

In light of all this, external mediation now seems crucial, especially with the failure of Washington and the African Union’s efforts.

According to an informed source, BRICS could play an important role in bringing the two countries closer together.

But the source expressed his fears that this could lead to tensions within the organization if each party was able to politicize the issue and attract some members of the organization to its side against others on the side of the other party.

“BRICS’ intervention to address the issue threatens to create divisions within it. The organization’s failure to intervene to resolve this dispute also undermines its value and effectiveness as an international organization”, he added.

Therefore, the source suggested that BRICS’s approach to resolving the Egyptian-Ethiopian dispute should be through a legal frame based on the arbitration of the rules of international law, especially those governing international rivers, as well as previous bilateral agreements signed by the two parties, without political bias towards one party at the expense of another.

But in my view, any sustainable solution to this conflict must be part of a comprehensive solution to the conflicts in the Horn of Africa, which range from ethnic ambitions to border disputes, in addition to the problems resulting from the unilateral actions of the countries upstream of the region’s many rivers against the countries downstream. The dispute over the Nile River is not the first and will not be the last.

Leave a Reply