By Dr Halim Gençoğlu

Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content.

Frantz Fanon

(The Wretched of the Earth)

(The Wretched of the Earth)

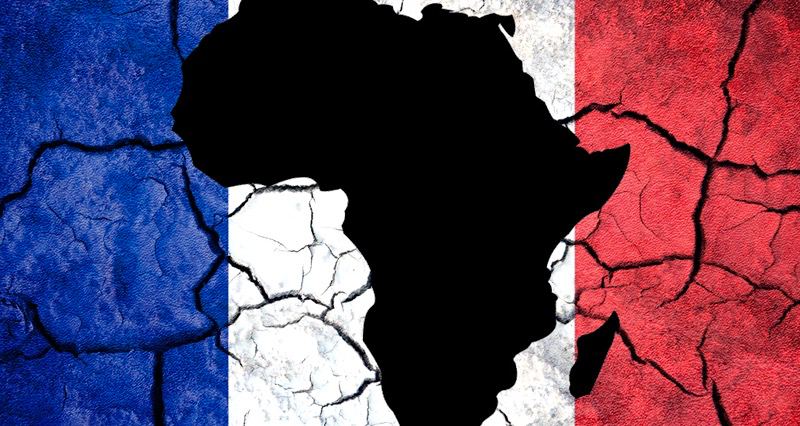

French colonialism in Africa, spanning from the 19th to the mid-20th century, profoundly impacted the continent’s political, economic, and cultural landscape. Driven by economic interests, national prestige, and the mission civilisatrice (civilizing mission), France established colonies across West, Central, and North Africa, including territories such as Algeria, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and Cameroon. French colonial rule was characterized by the imposition of direct governance, economic exploitation, and cultural assimilation policies, including the spread of the French language and education system. While colonial infrastructure development, such as railways and ports, facilitated trade, it was often aimed at resource extraction for the benefit of France. The colonial system led to significant social and political disruption, including forced labor, land appropriation, and the suppression of local customs and governance structures. Resistance movements and uprisings emerged throughout the colonial period, leading to nationalist struggles for independence in the mid-20th century. The legacy of French colonialism continues to shape post-colonial African states through linguistic, political, and economic ties, as well as enduring socio-economic challenges.

What occurred in Africa during French Colonisation

French imperialism in Africa left an indelible mark on the continent, profoundly shaping its political, social, and economic landscapes. From the 19th century to the mid-20th century, France’s imperialist ambitions spanned vast swathes of African territory, where the exploitation of resources, forced labor, and violent repression were central features of French colonial rule. This article examines the nature of French imperialism in Africa, focusing on the brutal massacres and oppressive policies that defined much of France’s colonial legacy. In Accumulation on a World Scale, Amin critiques how French colonialism set up economies that functioned solely for France’s benefit:

“The colonial economy was an appendage of the French economy, structured to serve the needs of the metropole by extracting raw materials while maintaining the colonies as markets for French manufactured goods.”

In the late 19th century, European powers scrambled to carve up Africa in what became known as the “Scramble for Africa.” France, eager to expand its global empire, established colonies in West, Central, and North Africa. By the early 20th century, France controlled one of the largest colonial empires on the continent, including present-day Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Mali, Senegal, Chad, Niger, Côte d’Ivoire, and Gabon.

French colonialism was characterized by the policy of “assimilation”—the belief that French culture and civilization were superior and that African societies should be remade in the image of France. This involved imposing the French language, legal system, and education on colonized peoples. However, beneath this veneer of “civilizing mission” lay the violent repression of African cultures, brutal economic exploitation, and a systematic disregard for the rights and lives of African peoples.

Brutal repression and massacres

The French colonial enterprise was marred by numerous massacres and acts of violence aimed at suppressing resistance and maintaining control over African territories. Some of the most notorious examples are summarised below.

Algeria (1830–1962)

The colonization of Algeria was one of the bloodiest chapters in French imperialism. The invasion began in 1830, and for over a century, France waged a brutal campaign to subdue the local population. Hundreds of thousands of Algerians were killed in the process, particularly during the early years of colonization.

One of the darkest episodes was the use of scorched earth tactics by French military leaders, such as General Thomas Robert Bugeaud, who advocated for the burning of villages, destruction of crops, and mass killings to break the resistance of Algerian fighters. By the time of Algeria’s war for independence (1954-1962), France employed even more brutal methods, including torture, summary executions, and bombings of civilian populations. The war culminated in the infamous Sétif and Guelma massacres of 1945, where French forces killed up to 45,000 Algerians after a series of nationalist protests.

West Africa

In West Africa, French colonial forces were responsible for numerous atrocities. In Senegal and Mali, resistance to French rule was met with devastating military campaigns. The French used modern military technology, including machine guns and artillery, to crush African armies armed with traditional weapons. Thousands of African soldiers and civilians were killed in battles or in punitive expeditions that followed. Aminata Traoré: In Le Viol de l’Imaginaire, Traoré criticized the continued exploitation of Africa under Françafrique, a neo-colonial relationship as follows:

“What we are living today is the continuation of colonialism, a system that left Africa divided and dependent. Françafrique has merely taken a new form, keeping us bound to France economically and politically.”

One particularly horrific episode occurred in Niger in 1899 during the Voulet–Chanoine Mission, a French military expedition. The commanders, Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine, conducted a reign of terror across the region, massacring entire villages and engaging in indiscriminate killings. Their brutality was so extreme that even the French government, usually indifferent to colonial violence, recalled them—though their rampage had already left a trail of devastation.

The Madagascar Uprising (1947)

The suppression of the Malagasy Uprising in 1947 is another dark chapter in France’s colonial history. The uprising began as a rebellion against French rule in Madagascar, where local leaders sought independence. In response, French colonial forces launched a brutal crackdown, killing an estimated 30,000 to 90,000 Malagasy peoplep over the course of 18 months. French troops engaged in widespread massacres, forced labor, and torture to quell the rebellion, leaving deep scars on the Malagasy population.

Cameroonian Repression

In the years following World War II, Cameroonian nationalists, particularly those affiliated with the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), began agitating for independence from French rule. The French government responded with overwhelming force, using colonial troops to crush the rebellion. From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, tens of thousands of Cameroonians were killed in counterinsurgency operations, and entire villages were destroyed as part of France’s efforts to maintain its grip on the country.

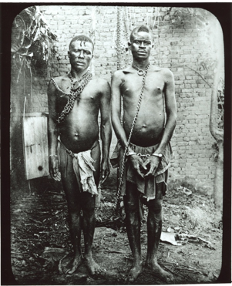

French imperialism in Africa was not solely defined by violent repression. Economic exploitation was also a central component of colonial rule. African labor was exploited to extract the continent’s vast natural resources, including rubber, cotton, and minerals. In French Equatorial Africa, for example, the colonial administration imposed forced labor on millions of Africans, who were compelled to work in horrific conditions to build infrastructure such as railways, roads, and plantations.

In French Congo (modern-day Republic of the Congo and Gabon), the exploitation of labor for rubber production led to the deaths of tens of thousands of people. The Congo-Océan Railway, constructed between 1921 and 1934, claimed the lives of as many as 20,000 African laborers due to brutal working conditions, malnutrition, and disease.

Independence movements and continued violence

The mid-20th century saw a wave of independence movements sweep across Africa, with many nations finally shaking off the yoke of colonial rule. However, the transition to independence was often bloody, as French forces attempted to maintain their hold on the continent.

In Algeria, the war for independence was one of the bloodiest conflicts of decolonization. The French military’s use of torture, mass arrests, and bombings in civilian areas during the war left deep wounds that still affect Franco-Algerian relations today. In Cameroon, Madagascar, and other parts of the empire, independence was also won through violent struggle.

Even after granting formal independence, France maintained neocolonial control over many of its former colonies, particularly in West Africa. Through a system known as Françafrique, France continued to exert economic and political influence, often supporting authoritarian regimes that suppressed democratic movements and perpetuated human rights abuses.

French colonial looting of African treasures

The looting of African treasures by France during the colonial period is a significant part of the history of exploitation and cultural destruction in Africa. These stolen artifacts include invaluable cultural and historical items such as statues, religious artifacts, royal regalia, manuscripts, and art pieces, many of which were taken during military expeditions or as spoils of war. French colonial authorities and private collectors looted these treasures from countries like Benin, Senegal, Mali, and Cameroon.

Once in France, these artifacts were displayed in museums, including the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, which houses thousands of African cultural objects. The removal of these treasures stripped African societies of their cultural heritage and left a deep scar on the continent’s history. The stolen items represent not only artistic value but also spiritual and communal significance, making their loss a profound violation of African identity.

In recent years, there have been increasing calls for the repatriation of these artifacts. African countries are demanding the return of their cultural heritage, arguing that these objects were unlawfully taken and should be restored to their rightful owners. Some progress has been made, with France committing to return certain items to Benin and Senegal, but the process remains slow, and the vast majority of stolen treasures are still in French museums and private collections.

The issue of stolen African treasures reflects the broader colonial legacy of exploitation and the ongoing struggle for justice and cultural restitution in post-colonial Africa.

A legacy of violence and exploitation

French imperialist policy in Africa was characterized by a combination of violent repression, economic exploitation, and cultural domination. The massacres and forced labor regimes inflicted untold suffering on millions of Africans, and the legacy of this violence continues to affect the continent today. Scholars such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o have discussed the cultural impacts of colonization, noting that French colonial policies often aimed to erase African identities and languages. The imposition of the French language and culture is seen as a means of undermining local traditions and promoting a sense of inferiority among colonised peoples.

As African nations continue to grapple with the aftermath of colonialism, the scars of French imperialism remain visible in economic inequalities, political instability, and ongoing struggles for justice and recognition. France’s colonial legacy in Africa is a somber reminder of the brutalities of empire, and it calls for a reckoning with the past and a commitment to repairing the damage inflicted on African societies.

Bibliography

1. Afigbo, A.E. The Warrant Chiefs: Indirect Rule in Southeastern Nigeria 1891-1929. Longman Nigeria, 1972.

2. Ajayi, J. F. Ade, and Michael Crowder, eds. History of West Africa, Volume Two. Longman Group Limited, 1974.

3. Akyeampong, Emmanuel, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, and James A. Robinson, eds. Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

4. Asiwaju, A.I. Western Yorubaland Under European Rule, 1889-1945: A Comparative Analysis of French and British Colonialism. Longman Nigeria, 1976.

5. Diop, Cheikh Anta. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Lawrence Hill Books, 1974.

6. Mamdani, Mahmood. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press, 1996.

7. Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. University of California Press, 2001.

8. Mudimbe, V.Y. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Indiana University Press, 1988.

9. Nkrumah, Kwame. Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. International Publishers, 1965.

10. Thiam, Cheikh Moussa Diouf. French Colonialism in Africa and the New World Order. Dakar University Press, 1990.

Leave a Reply