By Mehmet Enes Beşer

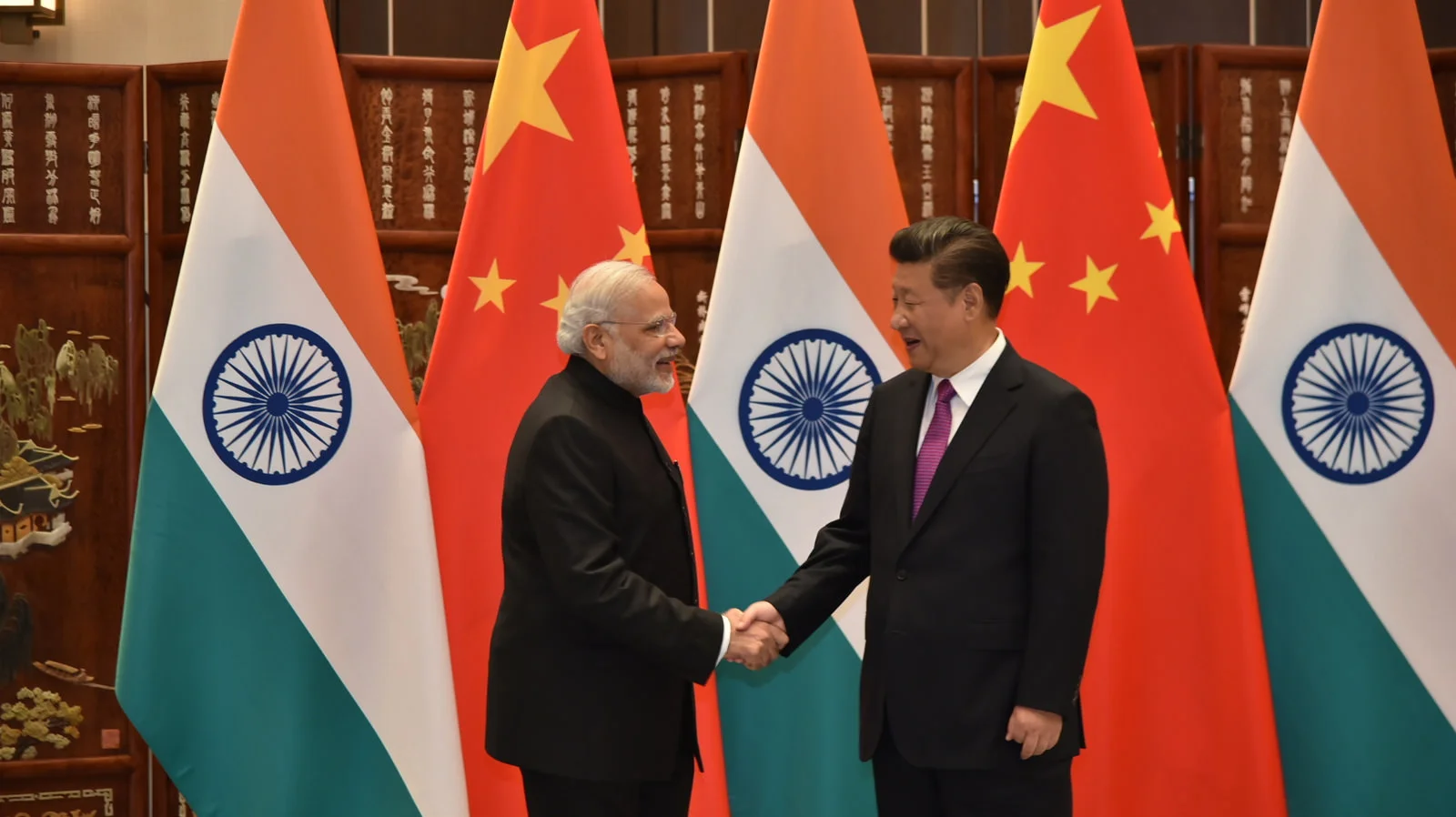

The world is being remade at its roots. As Western dominance declines, the Global South looks to emerging poles of power—China and India above all else—as possible sponsors of a more inclusive and just world order. These two regional giants, who collectively harbor more than a third of humanity, not only wield gigantic economic and geopolitical power but also symbolic weight to the shared hopes of the Global South. A protracted rivalry or increasing animosity between Beijing and New Delhi is not only undesirable in this new global order—it is inconceivable.

On all the open questions of the disputed border areas, it is now evident that this sensitive issue will not define the next five years of bilateral relations. Isolated military clashes can still continue, but restraint has been exercised by both governments and a realization that escalation is in no one’s interest. The real problem, however, lies deeper: China and India, despite all these centuries of civilizations coming into contact with each other and all these decades of diplomatic amity, still continue to be not sensitive enough to grasp each other’s strategic calculation, domestic motivation, and overseas desire. That failure of understanding—more than the border itself—threatens the greatest future instability.

Underlying this problem is a lack of concerted, institutionalized effort. Diplomatic dialogue, Track II diplomacy, scholar exchange, and people-to-people contact are all absent in ratio to the scope of the relationship. Failure to resolve problems at a communications level has allowed false assumptions and suspicion to build, too often filled out by sensational media hype and Cold War-era political grandstanding. Under such conditions, low-level goading gets ratcheted up to survival issues.

But the broader geopolitical setting makes cooperation not just possible but inevitable. The Global South, from Africa to Latin America to Southeast Asia, is looking for development models that are not Western templates. India and China have both followed different paths to modernity—China through statist industrialization and infrastructure, India through democratic politics and services-sector growth. These new but complementary paradigms offer the world an alternative to the current neoliberal orthodoxy. Yet, to make things heard, Beijing and New Delhi need to demonstrate that cohabitation is not only feasible—it is preferable.

On issues such as climate justice, global institutional reforms such as in the IMF and UN Security Council, South–South commerce, and vaccine equity, India and China are capable of joint leadership. Their potential power through their cooperation in institutions such as BRICS, the G20, and Shanghai Cooperation Organization can be mobilized. These must not be symbolical meet-forums—they should be used to establish a common vocabulary of confidence and practical accord on global priorities.

Apparently, there are structural imbalance and geopolitical fault lines that cannot be wished away. India is more and more aligned with the U.S. and its Indo-Pacific policy, and China feels it is faced with Western containment. Alignment with rival poles does not rule out bilateral cooperation, however. In fact, strategic autonomy—a term to which both nations are likely to be prone to lay claim—refers precisely to the freedom to act for national purposes without falling victim to preconcerted geopolitical plays. In the case of China, it will involve a refusal to let outside pressures dictate the China-India relationship to become an exclusively conflictual one.

What is needed in the next five years is not some master solution to everything but a low-key, step-by-step normalization of relations. Border confidence-building measures, the return of negotiations at all diplomatic levels, more cultural and educational exchange, and cooperative regional projects—particularly in the Global South—can be the basis of a new Sino-Indian balance.

Conclusion

The Global South does not have the luxury of Asian fragmentation. As the developing economies look to development-oriented, multipolar, and inclusive leadership, China and India have an obligation to look beyond history’s grievances and strategic suspicion. The border dispute, while outstanding, can be managed. The more fundamental challenge—and the larger opportunity—is to establish mutual understanding, trust, and shared global responsibility. Understanding one another will keep suspicion at bay.

By choosing engagement, not estrangement, and cooperation, not conflict, China and India can offer a vision of global leadership that responds to the aspirations of billions. The world over the next five years will be an experiment—not of power, but of maturity. And the world is waiting.

Leave a Reply