By Mehmet Enes Beşer

While the United States retreats inward, bedeviled by electoral division, budgetary crisis politics, and a protectionist revival of economic nationalism, fresh geopolitical momentum is building elsewhere. Across the Asian region and beyond, emerging and middle powers are increasingly reconfiguring the forms of international order—not so much by glittering declarations, and more so through persistent agential claims-making, economic remapping, and institutional innovation. No longer willing to take passively a system of unequal exchange and selective rule application, these countries are building quietly, but deliberately, alternatives designed to meet their own development agendas and political principles.

The post-Cold War era, dominated by the Washington Consensus and US multilateralism, promised growth through open markets, global capital, and technocratic governance. But to most Global South nations, the gains of globalization came in an unequal manner, with the baggage of debt dependency, premature deindustrialization, and environmental vulnerability. To most policymakers in Jakarta, Nairobi, or Brasília, the international system yielded discipline rather than development, compliance rather than partnership. The pandemic, climate emergency, and recent food and energy shocks simply compounded the view that global standards are written for the privileged few, while others bear the brunt of volatility.

As American commitment to global governance slackens—evinced in its retreat from multilateral treaties, erratic trade bargaining, and discretionary sanctions regimes—countries in Asia, Latin America, and Africa are taking the initiative to re-balance. They are not attempting to reproduce Western liberal order with a different face but to realign the very foundations on which global engagement is predicated.

Asia is at the forefront of this shift. The rise of regional multilateralism in the guise of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) signifies a clear departure from Western-led institutions. These platforms value adaptive engagement, infrastructure financing, and regional trade liberalization over conditionalities. They also point to a shifting gravitational axis: the Indo-Pacific is no longer just a great power competition strategic arena—it is the axis of global economic dynamism.

China and India, in spite of their very different international posture, both reflect the Global South’s determination to exercise economic sovereignty. China’s Belt and Road project has been accused of being debt-exposed and opaque, but it is also a grand experiment in reassigning infrastructure capital flows to previously unpenetrated regions of the world. India, meanwhile, has pursued a muscular development narrative centered around digital public goods, pharma autonomy, and rebalanced trade terms—quietly abandoning liberalization orthodoxy in favor of calibrated protection and state-led investment. Southeast Asian nations, to be headed by Vietnam and Indonesia, are employing supply chain rebalancing to present themselves as not merely passive recipients of investment, but as architects of a new geography of production that resists being dependent on the hegemony of a single power.

The shifting sentiment is not limited at the state level. In civil society, academic, and business communities in the Global South, there is a rising demand for epistemic diversity in the conception and implementation of development. The Euro-American standards—GDP-based models, Western environmental paradigms, or uniform liberal governance indicators—are being questioned more and more. Pluralism in development indicators, decolonization of knowledge, and South-South cooperation are becoming more popular. Initiatives like the BRICS New Development Bank or the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) are manifestations of this intellectual and institutional shift.

This rebalancing is not the end of Western dominance, but it is the end of its monopoly. The United States and its allies still wield gigantic capital, technology, and military might. But their ability to dictate the terms of globalization has declined. Washington’s tendency to oscillate between global leadership and domestic withdrawal—amplified under Trump and left hanging under Biden—has encouraged strategic fatigue among allies. Conditionality, double standards, and the weaponization of finance have alienated even seasoned allies, not to mention fence-sitting Global South countries. Sanctions regimes have demonstrated the worldwide reach of the dollar, but also its abuse. Alternatives, from China’s experiments in digital currency to South Asian barter-based oil trade, are not yet the norm—but they are rising.

Above all, the transformation occurring is less revolutionary than evolutionary. There is no new Bretton Woods, no one manifesto to replace the old. What we are witnessing is something more dispersed, and maybe more durable: a shift from global governance as hierarchy to global governance as negotiation. For Asia and the Global South more generally, that would mean room to set their own agendas—whether food security, climate justice, catching up technologically, or industrial diversification—without waiting for cues from Washington or Brussels.

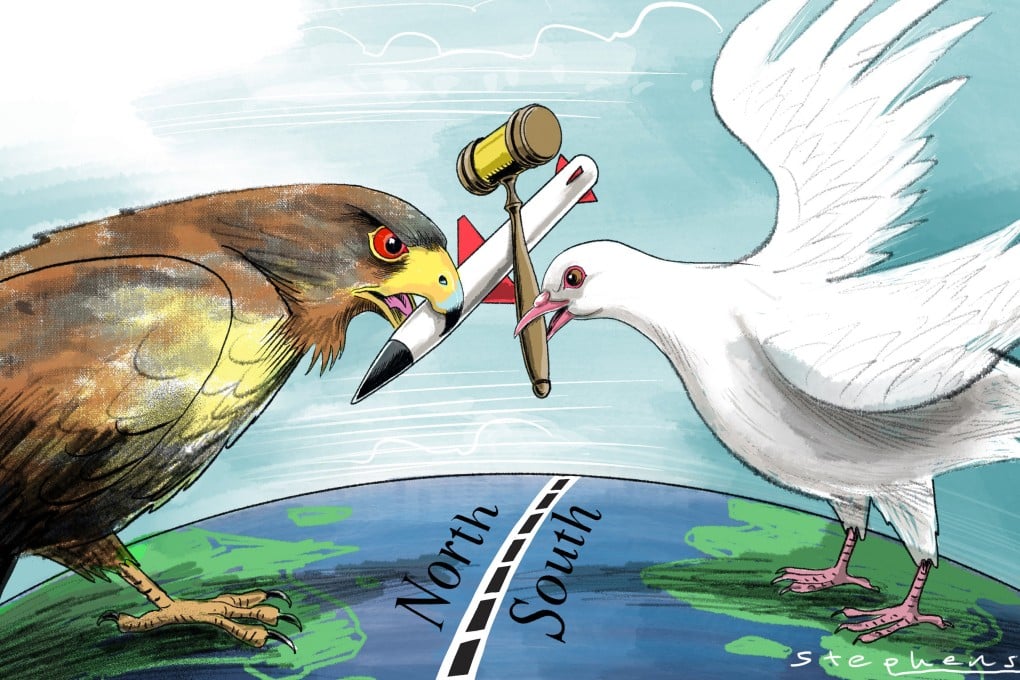

This new order is risky. Fragmentation can undermine coordination for climate goals, public health, or digital norms. Economic visions that are nationalist can double down on inequality or environmental devastation if they are not linked to responsibility. But the alternative—clinging to an unequal status quo—is not much likely to have legitimacy or last. There is finally an authentic competition over the world rule-making architecture—not just who makes the rules, but how and for whom the rules get made.

As the United States retreats from the leadership roles it had undertaken, the Global South is not collapsing in despair. It is building, rebalancing, and asserting. The question is no longer if a new order will emerge—but whether it will be of the aspirations, ambitions, and interests of the long-subalternized. In this peaceful turn, Asia and the Global South are not simply reacting to power vacuums—they are actively reshaping the global system to their own futures.

Cover graph by South China Morning Post

Leave a Reply