By Edvard Chesnokov

Imagine that in the breaking TV news, you are watching a cafe you used to drink your Oriental tea at — but now it is blown up by a bomb attack. For rich European or North American countries, such an image is almost unthinkable, their people sleep and wake upon clock alarms rather than street sirens.

But in most of the countries of Middle East — or, giving up with colonial terms, Western Asia — this is a constant reality. On January 22-23, 2023, I accompanied the official trip of the members of State Duma (the Russian parliament) to Iran. Among the delegation lead by the Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin, I walked across the yard of Iranian Majles — one of the largest parliamentary complexes in the world with a paradise-like park — questioning extreme safety measures we had to pass through to enter it.

But a week after, on January 28-29, the entire world watched fires and explosions over the warm Iranian night; reportedly, some of strikes occurred not far from the places we visited.

In its statement, the Iranian Ministry of Defense admitted that its military facilities were attacked by unidentified drones; precisely, as it was translated into Russian, the Iranian MoD used a term ’microbird’ instead of a ‘drone’ — I really respect Iranians who even in hard times don’t forget about rich Persian culture that might have been probably used a something-like-that word depicting the same existential battle between Good and Evil.

So far it is unclear who had driven the assault. Sources assumedly blame Israel, or the US from its military bases from Syria or the Gulf, or ISIS-style terrorists, as a kamikaze drone is easily to construct; moreover, in June 2017, ISIS had already conducted street attacks at multiple points in Tehran, including the Majles building — so our story has made a full circle and returned to initial point: the Russian parliamentary diplomacy in Iran and its neighbors.

In the last month, it was the second official visit of Vyacheslav Volodin and other MPs from Moscow to the notable countries of Middle East. In mid-December 2022, they have already come to Ankara and hold up joint workgroups with the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye.

Consequently — and a week after their Tehran flight — on January 29-30, Mr. Volodin with his colleagues have also visited one more country of the same region, Turkmenistan. In fact, such a frequency of the Russian parliamentary diplomacy is unprecedented (I would also remember a similar Volodin’s trip to Azerbaijan in October 2022), while the reason is clear: Moscow is designing its great geostrategic project of the largest common safety and energy zone at the largest continent.

You would ask, why Turkmenistan? A desert territory, with population 14 times less than Iranian and economy 22 times less than Turkish — Turkmenistan is, nevertheless, one of the most important countries of the modernity: this ancient land possesses the fifth (or, by some scale, even the fourth) worlds’ largest deposits of natural gas.

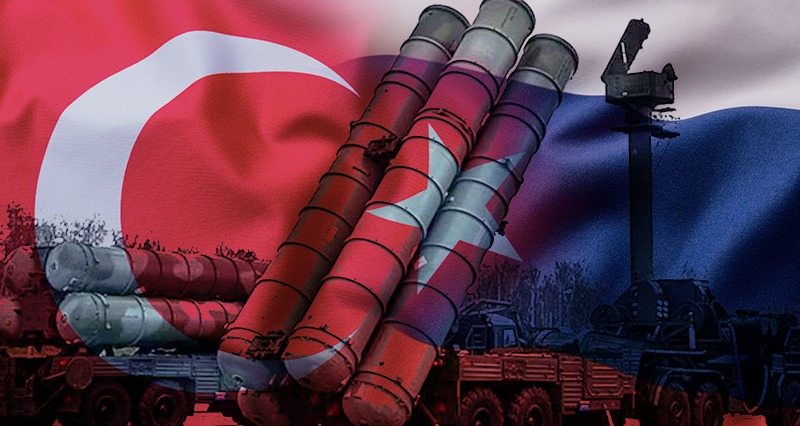

With Iran, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan, famous for their oil fields, this territory forms an energy island. Such a geostrategic body will be capable to supply entire 5-billion-populated Greater Eurasia with both black and blue fuel: to the West, there is Türkiye; to the East, there are China and Hindustan; to the South, there is Africa — the new industrial lands which can form an alternative order to the USA and the EU but desperately need sustainable supply of energy.

At the same time, to the North, lays Russia that is ready to sell out its fuel, coal, chemistry, fertilizers, grain, weaponry and even atomic power plants (the ones are already being constructed under the Russian projects in Türkiye, Iran, India, Bangladesh, and China). For last 9 years, every Moscow political analyst has been repeating that ‘abandoning the unfaithful West, the country is turning to the South-East’ — but only since 2022, the latter, after Russia was brutally kicked off the Western circle, is about to make a retaliate turn.

Thereby, in the same year, the trade volume between Russia and Türkiye had counted 100% increase to almost $60 billion — more than the Russian-German one. Same way, amid Russia and Iran, the trade had almost tripled, exceeded $4,5 billion annually. How could it be possible?

The answer is simple. Without Western political, cultural and sometimes military aggression — such an alternative alliance might have been never built. Sunni Türkiye, mostly-Shia Iran, and mostly-Christian Russia — all the main parts of this new North-South axis used to fight against each other for countless times. Perhaps Iran and Israel, or Türkiye and Greece, or Russia and the US had more in common than this trilateral alliance.

But, unlikely to the US-backed West, Moscow does not demand its partners to change their political design, religious values, and culture to favor the virtual concept called ‘liberal democracy’ — which will become your horizon line: you can lose all your power trying to chase it, while the West will be never satisfied by your transit-to-democracy progress. On the other hand, Russia always follows its previous guaranties to its allies: it helped Syria’s Assad to defeat terrorists in the 2010s; it helped Belorussia’s Lukashenko to handle the colored revolution in 2020 — compare it with the West which welcomed the 2016 coup attempt in Türkiye or ridiculously escaped from Afghanistan despite its own guarantees to the Kabul regime in 2021.

Moreover, every Russian official visiting its partner countries — either President Vladimir Putin, or Duma Chairman Volodin, or a governmental authority, or a MoFA diplomat — is endorsing the same and the single agenda I’ve already described, on the contrary to the West which is unable to reach consensus even within the Republican and the Democratic parties over the Middle East policy.

Obviously, unable to compete the new North-South axis openly, the West will try to save its dominance by unfair play. Now we see the artificially grown tensions in Karabakh — to disrupt the pacification between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Türkiye; endless third-part assaults to unleash a war between Azerbaijan and Iran; piteously, the same provocations amid the Central Asian countries are also upcoming, such as clashes on the border between Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, or the new boundary conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

But the countries which have already managed to handle the united Western pressure — such as Türkiye in 1919, or Russia since 2022, or Iran after 1979 — will be able to maintain their axis no matter what challenge they would face. Because at a long distance, fair players always overtake the unfair ones.

Leave a Reply