European colonialism spanned from the 16th to the 19th centuries, during which European powers expanded globally by establishing colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The process of decolonization began in earnest after World War II, as European empires started to dismantle. A pivotal moment in this process was the 1941 release of the Atlantic Charter by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. This document, which outlined the goals of the U.S. and British governments, included a key clause recognizing the right of all people to choose their own government. The principles of the Atlantic Charter were later integrated into the United Nations Charter, providing the organisation with a mandate to promote global decolonization. However, despite these efforts, modern postcolonial states exhibit significant differences in political and economic stability.

Historians typically identify two primary types of colonialism established by Europeans: settler colonialism and exploitation colonialism. Settler colonialism involved the establishment of towns and cities populated mainly by European settlers, creating a “Neo-Europe.” In contrast, exploitation colonialism focused on extracting and exploiting resources, often without significant European settlement. These two forms of colonialism often overlapped or existed on a spectrum.

Settler colonialism occurs when foreign citizens establish permanent or temporary settlements, known as colonies, in a new region. This form of colonization often resulted in the forced displacement of indigenous peoples to less desirable areas. Examples of settler colonies include those established in the United States, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Argentina, and Australia. Native populations frequently suffered significant population declines due to exposure to new diseases brought by the settlers.

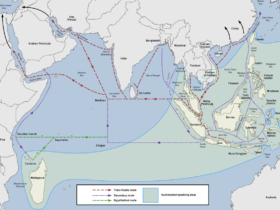

The primary motivation for resettlement was access to desirable territory, particularly regions free of tropical diseases and with easy access to trade routes. As Europeans settled these areas, indigenous peoples were forced out, and regional power shifted to the colonizers. This led to the disruption of local customs and the transformation of socioeconomic systems. Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani highlights “the destruction of communal autonomy and the defeat and dispersal of tribal populations” as key factors in colonial oppression.

Europeans often justified settler colonialism by claiming that they could make better use of resources and land than the indigenous populations, particularly through the introduction of modern agricultural practices. As agricultural expansion continued, native populations were further displaced to clear land for farming.

Scholars like James A. Robinson, and Simon Johnson theorize that Europeans were more likely to establish settler colonies in areas with low mortality rates from disease and other external factors. Many of these colonies sought to replicate European institutions and practices, granting settlers personal freedoms and opportunities for wealth through trade. As a result, jury trials, protection from arbitrary arrest, and electoral representation were often introduced to provide settlers with rights similar to those they enjoyed in Europe. However, these rights were generally not extended to the indigenous populations.

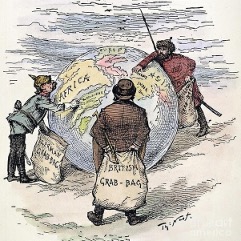

Exploitation colonialism refers to the colonization of a country primarily to control and extract its natural resources and labor. Since these colonies were created with the sole purpose of resource extraction, colonial powers had little incentive to invest in institutions or infrastructure that did not directly support their exploitative goals. As a result, they established authoritarian regimes in these colonies, with virtually no limits on state power.

Scholars like Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson argue that the institutions set up by colonizers provided minimal protection for private property and lacked checks and balances against government expropriation. The primary aim of these extractive states was to transfer as many resources as possible from the colony to the coloniser with minimal investment.

A notorious example of exploitation colonialism is the policies and practices carried out by King Leopold II of Belgium in the Congo Basin. Under the pretence of humanitarian efforts to end the slave trade, Leopold received international support to take control of the region, which was home to nearly 20 million Africans. Once in power, Leopold extracted vast quantities of ivory, rubber, and other natural resources, amassing what would be equivalent to 1.1 billion dollars today through brutal and exploitative tactics. Soldiers imposed unrealistic rubber collection quotas on African villagers, and failure to meet these demands led to violence, including holding women hostage, beating, or killing men, and destroying crops. These practices resulted in widespread famine, disease, and a significant decline in the birth rate, all at minimal cost to Belgium.

The Belgian system of governance in the Congo was marked by extreme authoritarianism and oppression. Many scholars attribute the roots of authoritarianism under Mobutu’s regime to these colonial practices.

Indirect and direct rule in colonial political systems

Colonial rule can be categorized into two main systems: direct and indirect rule. European colonisers faced the immense challenge of governing vast territories around the world, and their first solution was direct rule. This involved establishing a centralized European authority within the colony, run by colonial officials, where the native population was excluded from all but the lowest levels of government. Mamdani describes direct rule as “centralized despotism,” where natives were not considered citizens.

In contrast, indirect rule involved integrating pre-existing local elites and indigenous institutions into the colonial administration. This system allowed for the preservation of some pre-colonial structures and the development of local culture. Mamdani refers to indirect rule as “decentralized despotism,” where local chiefs handled day-to-day governance, but the real power remained with the colonial authorities.

Under indirect rule, as seen in India, the colonial power managed foreign policy and defense, while the indigenous population oversaw most aspects of internal administration. This system resulted in autonomous indigenous communities governed by local tribal chiefs or kings, who were either part of the existing social hierarchy or appointed by the colonial authority. Traditional authorities acted as intermediaries for the “despotic” colonial rule, with the colonial government intervening only in extreme cases. In some instances, indigenous leaders gained more power under indirect rule than they had in the pre-colonial period.

The primary aim of indirect rule was to allow natives to manage their own affairs through “customary law.” However, in practice, local chiefs often created and enforced their own unwritten rules with the backing of the colonial government, enjoying judicial, legislative, executive, and administrative powers, often with little regard for the rule of law.

European colonial women and the dynamics of direct rule in Benin

In Ouidah, Benin (formerly French Dahomey), European colonial women were often carried in hammocks by native labourers, illustrating the stark power dynamics of colonial rule. Under systems of direct rule, European officials exercised complete control over governance, relegating the native population to a wholly subordinate role. Unlike indirect rule, where colonial powers issued orders through local elites, direct rule involved European authorities directly managing administration, often replacing traditional power structures with European laws and customs.

Joost van Vollenhoven, Governor-General of French West Africa (1917-1918), emphasised this approach, noting that traditional chiefs were reduced to mere mouthpieces for orders from the colonial government. He stated, “Their functions were reduced to that of a mouthpiece for orders emanating from the outside… [The chiefs] have no power of their own of any kind. There are not two authorities in the cercle, the French authority and the native authority; there is only one.” Consequently, these chiefs were ineffective and held in low regard by the indigenous population. In some cases, those living under direct colonial rule secretly elected real chiefs to preserve their traditional rights and customs.

Direct rule sought to eliminate traditional power structures to create uniformity across regions. This desire for regional homogeneity fuelled the French colonial doctrine of Assimilation, rooted in the belief that the French Republic symbolized universal equality. As part of this “civilising mission,” European principles of equality were imposed through legislation abroad. In French colonies, this meant enforcing the French penal code, granting the right to send representatives to the French parliament, and imposing tariff laws as a means of economic assimilation. This forced assimilation aimed to create a uniform, European-style identity, often at the expense of native identities. Indigenous people in colonized societies were required to conform to European laws and customs or risk being labelled as “uncivilized,” which resulted in the denial of access to European rights.

Comparative outcomes between indirect and direct Rule

The long-term effects of direct and indirect colonial rule continue to influence the success of former colonies. Research by Lakshmi Iyer of Harvard Business School found that regions in postcolonial India that were governed indirectly by the British were better at establishing effective institutions and were more capable of good governance than those under direct British rule. Areas formerly governed directly by the British now experience worse economic performance and have significantly less access to public goods like healthcare, infrastructure, and education.

Briefly, colonisation is the process through which a foreign power establishes control over a region or people, often involving the settlement of its population and the exploitation of local resources. Western colonialism involved the expansion of European nations, such as Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands, into various parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. This expansion was driven by motives of economic gain, political power, and cultural dominance. Research indicates that the current conditions in postcolonial countries are deeply rooted in these colonial actions and policies. Factors such as the type of governance imposed, the nature of investments made, and the identity of the colonizers have been shown to influence the development of postcolonial states. Analyzing the processes of state-building, economic development, and cultural practices highlights both the direct and indirect impacts of colonialism on these countries.

Note: This is a summary of a book based on my notes from university lectures in English, which I have translated into Turkish. The book will soon be published in Istanbul.

Leave a Reply