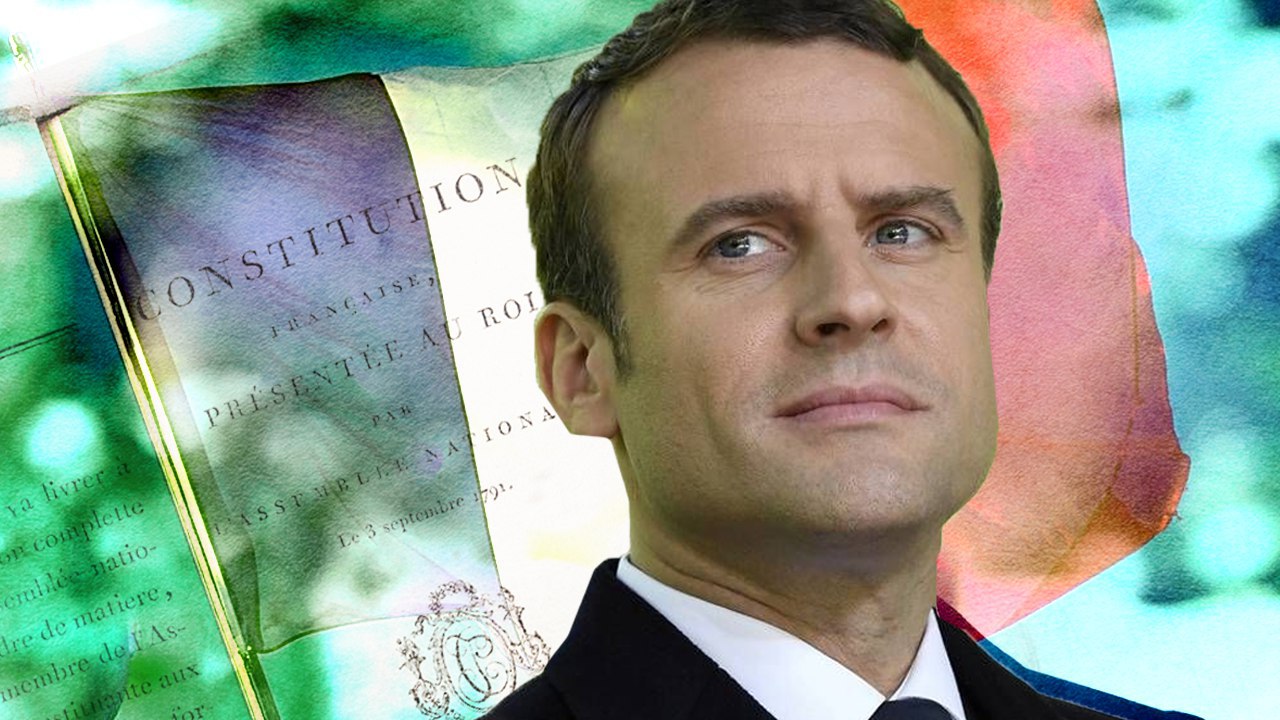

On Tuesday 14 July, Emmanuel Macron called for the fight against global warming to be included in the Constitution “as soon as possible”, a request made by the Civil Climate Convention. The head of state said in a television interview on July 14, believing that inclusion in the basic to help transform the country. At the same time, the President promised to allocate almost $17 billion for new funding of environmental programs.

Some experts attribute this to an attempt to “green” the political agenda after the failure of the presidential party in municipal elections – but the problems lie much deeper than a simple electoral race.

Macron’s Theses

Environmental proposals came from Citizens Climate Convention, an organization created immediately after the Yellow Vest protests. Macron met with CCC members on June 29, the day after the failed elections. At the meeting, representatives of the organization offered Macron 149 points of the environmental convention.

As a result, 146 were accepted and three were rejected: a dividend tax of 4%, speed reduction to 110 km/h on highways and the introduction of environmental protection as a preamble to the Constitution.

The first, according to Macron’s estimates, will reduce the willingness of companies to invest in innovation (critics laugh at the amendment, saying that this is how Macron simply protected big business). The second point has already become a concession to motorists – before that it was one of the annoying factors on a par with the diesel tax, which led to the streets of “Yellow Vests” (given that the strike was started by motorists who usually live in the periphery or out of town, they would be the first to oppose the speed reduction on the roads). The third point, according to Macron, is too much, because then environmental protection is put above civil liberties, above even democratic rules.

At the same time, Macron noted that he advocates a moratorium on new commercial zones on the outskirts of cities or the introduction of a tax on carbon dioxide emissions on the borders of Europe.

He specified some more specific possible measures: insisting on the thermal reconstruction of residential buildings, the latest models of cars, or hybrid, or electric, or gasoline, or diesel, but to a much lesser extent polluting the environment, the abolition of airlines when there is a railway alternative.

Macron’s theses stressed that there should be a vote in the Assembly first and then in the Senate, followed by either a congress or a referendum.

He believes that the environmental transition “has often been the (source) of misunderstandings in our country”, with the crisis, for example, “yellow vests”.

Stressing that he convened this Civil Convention precisely to overcome this contradiction, he said that he was convinced that we can build “another country in 10 years”. “We must find a common way to build a new environmental model,” he concluded.

A few weeks ago, the President said he would support the creation of making ecocide a crime in discussions with international organizations and that he is studying the possibility of introducing the concept into French law. The ecocide, one of the ideas supported by the Civil Convention, will concern serious environmental damage and will mainly concern the actions of companies.

The President promised to include in the measures the creation of an “environmental change fund” which will invest in environmentally friendly transport, renovation of buildings and industry of the future.

Green elections

Macron abruptly changed the agenda to a super-ecological one immediately after his party En Marche failed municipal elections (in postponed second round). Lyon, Strasbourg and Bordeaux; Besançon, Poitiers and Tours are all to be “greened” by the vote. Even Marseille, which has been a more “conservative” area for decades. The left-wing alliance brought Michel Rubirola, a candidate from the Ecology of Europe party, the French Green Party, to Marseille’s town hall.

It was also a successful day for the European “Ecology of Forest Werth”, the French “Greens”.

The results of the election confirmed that the “Greens” strengthened their positions, unlike the Macronists. The leader of the Socialist Party, Olivier For, even stated that he was ready to stand behind the candidate who represents the socio-ecological bloc in the 2022 presidential elections.

The socialists are also stepping on the heels of macronists: Anna Hidalgo, mayor of Paris from the socialist party, won re-election after easily defeating Rashida Dati of the Republicans and Macron candidate Agnes Buzyn, former minister of health.

However, some experts believe that the “greening” of France is not a populist trend, as the middle bourgeoisie in these cities voted rather against the main party in favor of politically active actors. That is, if you ask a Frenchman with less money what he thinks about greening, he is more likely to be uninterested in this topic, focusing on survival with strangling taxes. But the bourgeois city electorate is not so stable in its electoral decisions, the choice is rather situational, so next time they may vote for someone else. But even if in the case of France there is no real Green Wave problem among the people.

Macron’s cynical strategy to keep his presidential ship afloat for the next two years is to do to the green movement what he did to the Social Democrats in his quest for the Elysian movement three years ago: suck the life blood out of the movement, change into its colours and use their players.

But while it will not be easy for Macron, his green and left-wing opponents, who continue to quarrel with each other both politically and organizationally, do not represent a real alternative either. Above all, the green and left winners in this election are far from being able to offer the only thing that the French electoral system requires when you want to change the fundamental direction of national politics: a single, strong leader who is truly capable of winning.

Hence Macron’s maneuvers. Partly he was playing on the left flank with talks about “Europe”, an open vision of opportunities, willingness to accept changes in social relations. For the last two years he has been playing on the right with his economic reforms, with “security” measures, with police brutality. In fact, he has been conducting neoliberal reforms under the guise of progressive reform.

Power changes and neoliberal measures

However, after the election, there were other changes in the political establishment: Edouard Phillippe resigned, and Macron took over Jean Castex instead. The unknown Prime Minister Castex, according to experts, strengthens the already increasingly centralized presidency of Macron.

Within a few weeks, Macron had already made it clear that he was working on a “new course” after the lockdown. The fact that Macron is in fact only talking about the environment, but is not going to “green” the country, and that he has replaced one centralist bureaucrat with another – only even less politically colored. In his first interview on TF1 news channel, July 3, Jean Castex said ecology would be “at the centre of priorities”. “To make the French economy the most carbon-free in Europe. Ecology is a matter for all of us,” he concluded.

However, the main curtesy to the Greens was the appointment of Barbara Pompili, a former green who joined Macron’s party, assigned to the Ministry of the Environment.

Macron’s entourage insists that the new team does represent a renewal. Castex, they say, combines knowledge of how to drive a Parisian administrative car with local connections. He has a reputation as an efficient employee at a time when Macron has already tarnished himself with neoliberal reforms and bureaucracy. Perhaps, with the help of Castex’s image, Macron wants to try to visually reduce the distance from people in the field, while Castex is convenient as a controlled neutral manager.

The weakness of the establishment

It’s important that Macron himself publicly acknowledges his weakness. During an interview at the Elysian Palace, Emmanuel Macron expressed regret about the “crisis of confidence”, while admitting that he is the object of “disgust”, which sometimes feeds off his own “blunders”. He admitted that he had failed to become a president who reconciled the French:

“We lived through a social crisis with the ‘yellow vests’ which was the anger of a part of the French people, who (…) said to themselves: ‘This world is not made for us. The reforms they’re making, what they’re asking us to do is not for us.”

Macron has a lot to worry about: since the “Yellow Vests” mass protests, which even went beyond France, he has already lost the rest of the people’s trust. After the diesel scandal, he has made other attempts at neoliberal reform, including unfortunate pension reform and an attack on unemployment benefits. Also worth mentioning is the unpopular university bill, which will further reduce the number of permanent contracts and divide universities into two categories – well-funded “centres of excellence” and second-rate universities for less privileged classes (i.e. the rapidly becoming poor middle class). Castex announced its intention to begin negotiations on pension changes, which Macron said would “be transformed,” but “will not be abandoned”.

By pushing his previous high-profile prime minister, Macron indicates he intends to run the show further. Just this time in green and more “populist” tones, but with the same interest in the well-being of bankers and big businesses.

But since Macron takes more power, betting on the faceless and submissive Castex, he himself is raising the stakes for further failures and will have to answer for himself.

On July 14 in his address, Macron stressed the need to restructure the economy and create new jobs in environmentally oriented projects, including the development of more “green” transport. He hopes that a change of image will help him in the upcoming presidential elections – on the one hand, as a champion of stability and sovereignty, on the other, as a fashionable environmentalist.

What this new president is silent about is that all this will require new large expenses, and the growth of public spending will lead to an increase in public debt. It is possible that Philippe was removed for this reason among others – as a fiscal expert, he would be against these measures.

At the same time, money for ecological transition cannot come from people who are already struggling to survive…

Greening Europe

The Green Wave in Europe is rather a phenomenon on the electoral and political level, given that it is not an important agenda as it is “among the masses”.

In Ireland, the new coalition of Fianna Fail and Fein Gael depends on the support of the Green Party, which will insist on a commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 7% per year. Austria is governed by an alliance of the populist right-wing People’s Party and the Greens. Environmental targets are being accelerated and the Green Minister for Climate Protection, Environment and Energy aims to make Austria carbon neutral by 2040. The European Parliament bloc dominated by the “greens” is also a force to be reckoned with. Even in Germany, polls give a good forecast for Die Grünen.

But the subpoena is becoming a kind of totalitarian mainstream at the top, while the bottoms behind the lack of social security and think about eco-city.

The European Parliament’s website has even defined a new regulation for EU member states to ensure a “sustainable environment”, which (so far voluntarily) countries should be guided by.

Parliament has already passed new legislation on sustainable investment. It sets six environmental goals, including mitigation of climate change, economic change, etc. Establishing clear European “green” criteria for investors is key to attracting more public and private funding so that the EU can become “carbon neutral” by 2050, the website reports.

The Commission will regularly update the technical criteria for checking transition and incentive measures, the authors of the initiative note.

In other words, EU policy is now increasingly imposing ecocracy on member states – without asking or addressing what really worries the people of these countries.

Greenwashing

Turning back to France, the coronavirus pandemic has played a role in triggering the ‘green’ impulse: the impact of the pandemic on globalized supply chains has led to a renewed emphasis on food security, local production and environmental standards throughout Europe.

These are good initiatives when it comes to the environment, but there is one problem: as we have mentioned above, the victories of the “greens” have come mainly from young bourgeois voters living in relatively prosperous cities. But in many rural areas and small towns in France, where protests in yellow vests were triggered by higher fuel taxes, environmental radicalism is seen as a luxury option for the wealthy middle class of a metropolis. And ordinary people are not interested in constitutional amendments on environmental issues at all.

In the case of most environmental politicians, “green rhetoric” is not a real action to save nature, but a manipulation of scientific concepts (in which the average citizen does not understand) and Greenwashing – a form of economic marketing, which extensively uses “green” advertising in order to mislead consumers about the goals of the organization or producer in the environmental sustainability of a product or service, to present them in a favorable light. The technology is used by dubious producers to create an image of an environmentally friendly company and increase sales. But the term can also be interpreted more broadly, in a political context, as an attempt behind Green initiatives to conceal market redistribution, patronage of their business environment, or an attempt to achieve specific political goals in their own interests.

All businesses and brands are beginning to use the word “sustainable” in their marketing (note that this term is also used by the European Parliament in the proposed eco-regulation). Whether it is an ethical cotton T-shirt or a “green” car, companies are increasingly seeking to showcase their “green” qualities.

Sometimes greenwashing can be harder to detect and is much more insidious. It is here that companies and brands use words such as “green”, “eco-friendly” simply as a marketing ruse without thinking about the real meaning of these concepts. And, most importantly, without any responsibility for their actions.

McKinsey found that Gen Z (people born around 1995-2010) spend more money on companies and brands that are considered ethical.

“More than any other generation that came before, Generation Z is more prepared to open their wallets for a brand that promotes causes about social impacts, such as climate, LGBTQ, racial or social justice,” says Sertac Yeltekin, the COO of Insitor Partners, a Singapore-based, socially focused venture capital fund.

“This gives them unprecedented power to shape the success or downfall of companies. They are intrinsically aware that they can drive this corporate change.”

Now let’s shift this to policies that are closely linked to the economy.

What is good about the concept of ecology in relation to politics is that it adapts to almost any sauce: liberalism, communism, authoritarianism, socialism, says Le Monde Moderne.

It is easy for LREM to define a political environmental project, taking into account the citizens’ climate convention established at the initiative of the president, a permanent think tank that allows the president to demonstrate a false participatory democracy and, in fact, to engage in greenwashing, which is widespread in big business and international finance.

It is very important that in France, the most important areas – for example, the same transport that Macron likes to talk about – are given to private business, which forms a strict market price policy. It is this capitalist system that Macron is not even attempting to soften – there is no mention of nationalizing vital enterprises. All that can be understood from his proposals is that the authorities are looking for a good excuse for additional tax collection and encouragement of large banks.

In France, for example, it turns out that tax gifts are for investors like CICE bio, and sanctions are for the middle class, which does not think about ecology. Thus, the project will accelerate, for the benefit of all and the planet, the further increase in inequality, and without taking into account the most important element of real political ecology – human beings, the publication LMM notes.

Once again, the amendments aimed at forcing companies that use public money to reduce their emissions have been completely rejected. Including the group defended by En Commun (a group of majority members of parliament, including Barbara Pompili, the former “green”).

Thus, Macron does not care about the environment itself. He cares about money and his personal globalist connections. And that applies not only to France, but to many European politicians.

It is not Macron who represents ordinary people, but movements such as the Yellow Vests, which oppose the entire system. Yes, environmental care is necessary and important – but not from above, as suggested by banker candidates.

Many experts point out that true “political ecology” is only possible from the bottom – with initiatives from the working majority, which are not engaged in greenwashing at the highest level. One could call it “populist ecology”. If ordinary people have at least minimal social guarantees, they will be able to take care of trees and water bodies themselves – there is no need to create expensive commissions or change one big ruling business to another. Natural ecocracy is only possible in fair societies where the president cares for the environment as much as for his own citizens.

Leave a Reply