East Asia, or the Indo-Pacific as the United States calls it, is becoming increasingly a region of local and global tensions. The global conflict evolves mainly between the United States and China, regional conflicts among countries of the region follow. Foreign policies of China, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines tend to reflect increasing regional tension.

In that context, the activist organization Shiso-Undo from Japan makes a different proposal – one that tries to overcome regional differences by establishing the political identity of “East Asian”.

The organization presents this idea as a clear rejection of assertive Japanese foreign policy and nationalism. The following text, published in Japanese and translated by the organization itself, investigates the position along schoolbook texts and education.

United World International considers that this is an interesting analysis of the Japanese history and politics along construction of identity and ideology and presents the text to its readers.

By Takai Hiroyuki – Association for Supporting the School Textbook Screening Lawsuit in Ehime

Proposal: Let us Overcome the Concept of “Japanese Education” and create that of “the People of East Asia”: Who will stop the war in East Asia?

Education to create “we” and “they”

The purpose of education in a modern nation-state is to create “we” that is distinct from “they.” In the case of modern Japan, this mean that the diverse people who lived in various parts of the archipelago were to be given an identity of “We the Japanese” and a sense of belonging to the new nation of “Japan.” The new Meiji state, with the emperor at the core of its new “imagined community,” was working to build a sense of “we” by carrying out this process.

For example, at the end of the Edo period, when the Choshu clan fought a war against the Allied Fleet formed by the United States, Britain, France and the Netherlands, it was “their war,” not “our war,” for many residents who were not vassals of the clan. However, after the new Meiji government was established in 1868, most of the residents of the archipelago became aware of “their own country” through the education of nationalistic subjects and naturalization in schools, the military, and festivals, through the “indoctrination and integration” function of newspapers and magazine media, and above all, the actualization of “they” as an enemy nation appeared. Through this process, the “Japanese” became “we Japanese.”

Thus, the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars, which took place some 30 to 40 years after the end of the Edo period, became “our wars” for the people and subjects of the archipelago. The “we versus they” structure of modern Japan had been created.

“We” in postwar Japan

The “We” consciousness in postwar Japan can be roughly categorized into “We Japanese who inherit the Empire of Japan” and “We, the postwar democratic Japanese nation,” who prevent the inheritance of the Empire. Of course, reality is not so simply divided into two categories, but I would like to use this categorization here as a way of explaining the reality at hand in an easy-to-understand manner.

The “history textbook issue” that the author has been asked to write about can be said to be the issue of the rewriting of textbooks by the government, the LDP, and right-wing forces over the past 20 years in order to create this “Imperial Japanese” consciousness. As the slogan of former Prime Minister Abe and others states, this was an important part of the work to “break away from the postwar regime” (i.e., the postwar democratic constitutional system) and “restore Japan (i.e., Imperial Japan).” The basic structure of this issue is that people and organizations on the side of postwar democracy have been opposing this activity. Today, by the way, the U.S. government, under the guise of “tyranny versus democracy,” has encircled China and Russia, and in the latter half of its weakening, right-wing forces has begun to roll back. Soon after, these forces began to exert a strong influence on Japanese society, and now occupy the center of the postwar Japanese nation. During the past 20 years, education and textbooks have been drastically changed by these governments and forces. The Fundamental Law of Education, which was in a position to support and nurture the postwar democratic constitutional system, was changed, under the first Abe administration. And the consciousness of “We” of the democracies (the Western camp) in the world are shared by both the national and the international level. Below, the author would like to briefly describe the problems that both sides have.

The right-wing forces, feeling threatened by the social and political developments in Japan in the early 1990’s, which acknowledged and apologized for Japan’s aggression and colonial rule, have adopted a strategy to maintain their own unipolar rule (i.e., “tyranny” over the world) by transforming its tactics.

The Japanese government and right-wing forces, while intensifying their efforts to revise the Constitution to deny the postwar democratic Constitution, are acting in concert with this U.S. strategy in the name of a democratic nation externally. On the other hand, opposition parties that seek to protect the postwar democratic Constitution are also joining in the U.S. “diplomatic boycott” of the Beijing Olympics and other efforts to encircle China based on this “composition” of the U.S. strategy. At this time the authorized textbook was revised to have a more patriarchal and nationalistic color (2006). In the 1990’s, history textbooks, which had begun to address Japan’s perpetration of the war, were revised tragically.

For example, Tokyo Shoseki, which was said to be closest to the policy of the Ministry of Education, at that time (late 1990’s) began to include full-page feature articles on the forced deportation of Koreans by Japan and atrocities committed during its occupation of Southeast

Asia. It also increased its coverage of the facts of Japanese perpetration during the war. However, now the description of the atrocities is only a dozen lines (in the edition published in 2007). This is what happened in the early 2000’s when textbooks produced by right-wing and nationalist groups (“Association for Creating New History Textbooks,” Fusosha and Ippo-sha) appeared in the market and were adopted by boards of education across the country.

During the era of the Japanese Empire, “History (National History)” was the core of education for creating loyal subjects, along with “Shushin (Moral Training),” which was based on the Imperial Rescript on Education. The “Special Subject of Morals,” which overlapped with the “Major Subject of Shu shin (Moral Training),” Of course, this is not a “revival” as it is, but the apparatus for narrow-minded “Education for Nurturing Japanese Nationalism” is already in place.

“We” as the Western democratic camp

The so-called “postwar democratic forces,” the opponents of the above-mentioned right-wing movements, have resisted, however insufficiently, the succession and revival of Imperial Japan in the domestic political arena.

However, they have been weak in questioning Japan’s “foreign actions.” The (mainstream) postwar peace movement has positioned itself as a “victim of war” and has not questioned the “violation of aggression” to any great extent. This has led to a weak attitude toward questioning the “foreign actions” of the postwar Japanese nation. Postwar democracy has not strongly questioned postwar Japan’s economic aggression and complicity in the U.S. war of aggression.

The Western democracies (the mainstream) and the postwar democratic camp in Japan (the mainstream) share a common refusal to question their own “foreign actions”-imperialism, even though they have questioned the nature of the domestic political system. While they may take issue with the aggression of “despotic Russia,” they have little awareness of the aggression of “democracies” and their colonialism and imperialism.

This is what the Japanese government and many of the Japanese people are attributing to “We, the Western democracies.”

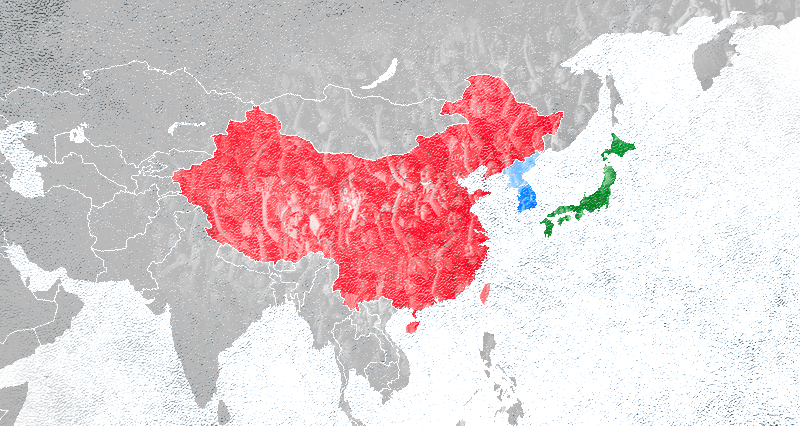

We, the People of East Asia

When the U.S., Japan, Europe, and the West are laying the “fuse to war,” that is, building a siege to China under the guise of “tyranny versus democracy,” we must raise a broad debate to ensure that people and organizations that support the postwar democratic Constitution will not be included in that “siege,” however unintended, in the name of “democracy.” We must also aim to build an anti-war solidarity movement with the people of East Asia, with the awareness and attitude that it is “we, the People of East Asia” who will prevent war in East Asia, transcending the division created by “tyranny versus democracy.”

Published in SHISO-UNDO, No 1080, SEPTEMBER 1, 2022

Leave a Reply