Reporting from Cairo / Egypt

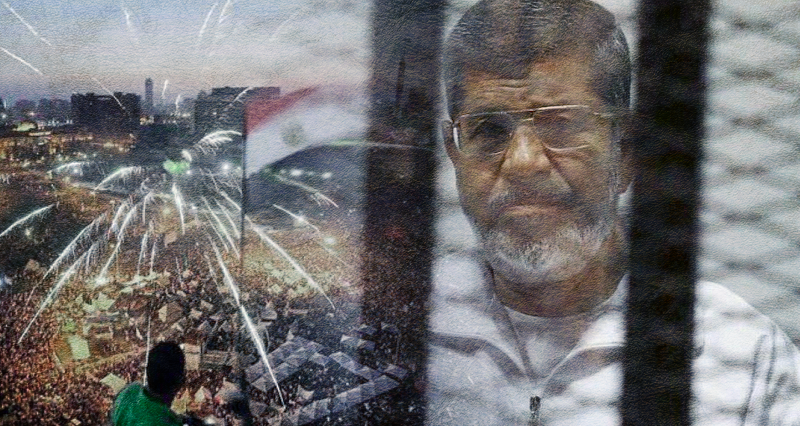

These days, Egypt celebrates the 10th anniversary of the massive demonstrations that took to the streets calling for the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi, who belongs to the Muslim Brotherhood. These demonstrations were known as the June 30 revolution. They erupted only two and a half years after the January 2011 revolution that overthrew his predecessor, President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak, who had ruled the country for 30 years. Mubarak was the air force commander who participated in achieving victory in the October 1973 war against the Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula.

The revolution against Mubarak aimed more at preventing the succession of power to his son Gamal, while the revolution against Morsi aimed more at preventing the country from falling into the grip of a theocratic rule. The latter had turned against the gains of Egyptians during the last two centuries with claims and allegations dating back to the Middle Ages.

Obvious fact

But the most obvious conclusion that can be drawn from the occurrence of two successive revolutions in such a close time frame is the following: Egyptians hope to establish a normal democratic system that guarantees the rotation of power, imposes accountability, and protects public and private freedoms – this hope remained alive and burning.

But now the question comes to mind: After 10 years of calming the anger of the Egyptians, can it be said that they succeeded in what they wanted to achieve? And if they fail, do they still have their old hopes? Perhaps the answer is much more complex than they imagine.

Everyone, including the current ruling regime, agrees that Egypt lost more than it gained in these two revolutions. But each of them has a different perspective on that loss.

In the view of President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, Egypt lost much of its monetary reserves and economic capabilities due to the chaos that swept the country during the two revolutions and the events that followed.

In many of his statements, Sisi blames Egyptians for their complaints about the difficult economic conditions. His mouthpiece: Don’t you want to pay the price for the change you wanted?

Egypt and the Egyptians really paid a heavy economic price for their desire for change, but did they really get it?

Freedom versus chaos

From the point of view of the opposition, political and human rights activists and others, the margin of political and media freedoms has declined to suffocating levels in a way that makes what prevailed during the era of President Mubarak an unattainable wish.

The opposition blames the ruling regime for wasting the opportunity of overwhelming popular support that it brought, which would have allowed it to establish transitional justice and a democratic system.

From the point of view of the opponents, the regime took advantage of this popularity to restore exceptional laws and procedures to consolidate its power, and even worked to amend the constitution to legalize the intrusion of sovereign institutions to ensure the return of the July regime that was established after 1952, in which successive army generals ruled with absolute powers.

The ruling regime justified all its exceptional measures by claiming that it was a response to preserve the state and prevent its collapse in light of the huge security flow that allowed waves of fierce terrorism to strike everywhere. But the mouthpiece of the regime was that freedom is synonymous with chaos, and that it will not allow any repetition of what happened 10 years ago.

As for ordinary citizens, who were seduced by the longing for change that an improvement in their living conditions would inevitably come, they are bemoaning today a blessing they lost in the past.

Squander opportunities

Citizens and economists blame the ruling regime for wasting the economic opportunities that became available to the country after the overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood regime.

According to them, the regime’s priorities were not feasible or economically profitable. They say that the regime has squandered the billions of dollars that the Gulf States provided to Cairo as grants and aid, as well as the loans it obtained from international financing institutions, on useless projects. They claim that the many taxes and fees imposed by the regime on citizens have made their lives more difficult.

The business community blames the massive expansion of the military’s economy for the loss of many domestic and foreign investment opportunities.

However, the regime justifies this by saying that it has taken over a country that is economically exhausted, its infrastructure needs massive development and suffers from structural economic problems, and it had no alternatives but to work in all tracks and at full speed, whatever the cost and whatever the implementation arms.

In sum, Egypt, after 10 years, has not established a stable democratic system that accepts freedom of opinion and allows the transfer of power. On the contrary, it has reverted to a new version of absolute rule, and has not succeeded in establishing an economic prosperity that will reflect positively on the living conditions of Egyptians. The worst thing is that the country is struggling with a hard currency crisis and Its debt numbers are at alarming levels. So why did the Egyptians fail to achieve their goals?

July regime continuity

It can be clearly said that not all agree upon the form of the desired state, just as the process of transition to democracy itself is not a matter of consensus between the people and the institutions of the deep state. In addition, the regional turmoil makes advocates of a gradual and calculated transformation within state institutions reluctant to take risks. At the same time, the interests of influential players at home and abroad are diametrically opposed to this ambition.

There are absolute systems of government in the region based on either family rule or one ruling party, but the absolute system of rule in Egypt is always based on the army.

Although everyone who ruled Egypt after the July 1952 revolution came from the army, with the exception of Morsi, the ruler used to come by a very restricted referendum or election and relied on a dominant party.

The July Revolution was a movement of change carried out by army officers to overthrow a crumbling monarchy in light of a turbulent regional situation in which Jewish gangs took control of the Arab land of Palestine amid international collusion, and an occupying British force retreated globally.

At the time of the outbreak of the July Revolution, the party system in the country was in a state of stagnation and decay. In the opinion of the leaders of the revolution, it was no longer possible to rely on these rival parties to achieve the aspiration of Egyptians to end the occupation and establish social justice.

Abdel Nasser’s state, which was formed after the expulsion of the colonialists, succeeded in bringing about a radical political, economic and social change. Despite the end of this regime with a heavy military defeat and the loss of the territory of the Sinai Peninsula, this situation was taken as a pretext for his deputy, Anwar Sadat, who came from the ranks of the army and one of the leaders of the July Revolution, to succeed him.

Although Sadat’s success in liberating the land and concluding a peace agreement with Israel could have been a starting point for the establishment of a new regime that would allow for more freedoms and the transfer of power, his assassination at the hands of terrorists and the attempt of others to seize the Asyut Security Directorate in 1981 was a justification for the continuation of the generals in ruling the country and choosing his deputy Hosni Mubarak, coming from the Air Force, to be the president.

Nobody is ready for the game

With the outbreak of the January 2011 revolution, one of its goals was establishing a democratic regime. There was no political organization ready to win any elections except for the Muslim Brotherhood, which has no convince of the basics of governing modern states.

With the arrival of the Muslim Brotherhood to power, the Egyptians lost an opportunity to transition to democratic rule, and the July regime found a justification for continuing to rule.

The military establishment sees itself, and Egyptians agree with it, as the sole guarantor of the stability of the largest Arab country. But the July regime that emerged from the institution created rules and institutions that indicate that it does not see any entitlement to others in ruling, even if it did not say so explicitly.

The rulers of the July regime shrouded themselves in all formal requirements, such as elections and the constitution, but practices degraded citizens, as they were not qualified to choose who would rule them, and politicians and parties, as they were only good at theorizing.

The July regime, with its various editions, used a wide range of traditional and rural powers that are easy to control through an economic and bureaucratic system that allows the distribution of benefits to loyalists and supporters.

As for the Muslim Brotherhood, which profited politically from being persecuted by successive regimes, it had nothing but a religious discourse that was not fit for the necessities of the modern era, and it did not see in the elections anything but a wooden ladder that that it seized after winning power to monopolize the right to change the shape of society. A wide range of religious and Salafist currents in Egypt have the same view of democracy.

In the face of these two views of democracy, which are adopted by the army and the Islamists, the political elites justify their failure on allegations that long decades of absolute rule did not allow the parties to freely communicate with the masses and accumulate experiences that would make them ready for the game of transferring power.

So the basic forces in society themselves do not agree to establish a democratic system, and even the forces that believe in it did not take the opportunity to present themselves as a serious alternative.

Unwelcome guest

On the other hand, Egypt, with all its weaknesses and problems, is capable of turning into an inspiring model. Therefore, many regional players fear Egypt’s transformation into a democratic state, fearing that this would be a contagion would spread to their countries.

Therefore, supporting the continuation of the July regime was a solution that would achieve stability in the country and prevent it from falling into chaos, and at the same time prevent the infection of the inspiring model.

Since Egypt was a country suffering from structural economic problems that made it unable to get rid of excessive appetite for borrowing, regional players found an opportunity to influence the Egyptian political scene after the June 30 revolution with money and the media in favor of supporting stability and a regime based on the rule of a general from the army.

Even the Western powers found in the short experience of the Brotherhood a warning bell that the country would fall into chaos, like some of its neighbors. These forces found in the continuation of the military-led absolute rule a guarantor of the stability of the country and the region, and avoided any risk to their interests in the event of the emergence of a new regime whose orientations are unknown.

During the past 10 years, democracy did not reach Egypt, because all parties treated it as an anti-stability case, and therefore it was unwelcome guest.

Despite the deterioration of the living conditions of many citizens during the past years, Egyptians did not respond to all suspicious calls to take to the streets, aware of the danger that this poses to the security and stability of the country.

As they watched the election battle in Türkiye last month, the people of Egypt felt envy. The scenes coming from the other side of the Mediterranean fueled nostalgic people’s longing for the dead democracy. They do not now find a way out of their economic and living crisis except through real and serious elections, so will the regime allow them to do so?

Leave a Reply