by Yiğit Saner, reporting from Rome / Italy

The energy crisis in Europe, a consequence of the geopolitical developments of recent years, together with the increase in the prices of fossil fuels and the expectation of filling the energy deficit with sustainable energy, force the Old Continent on the one hand to find new markets and, on the other, to look for new sustainable energy sources that can be used in heavy industry: Hydrogen.

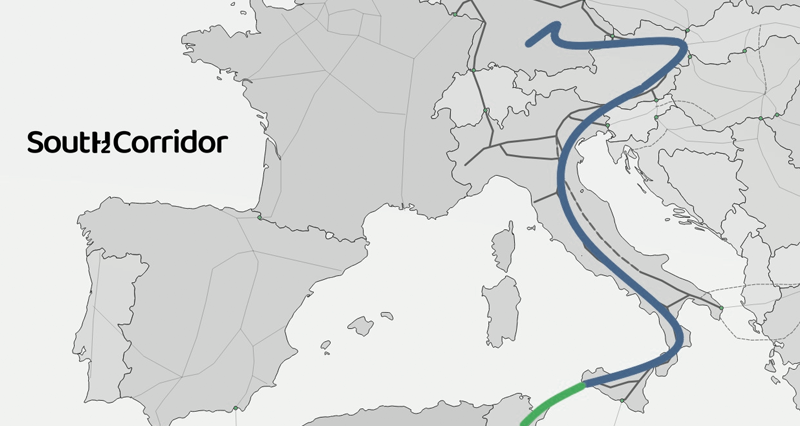

It is in this context that Italy, Germany and Austria announced in June a joint project to transport green hydrogen from North Africa to Europe: the SoutH2 Corridor.

From Rome to Berlin

The project was presented on March 23 in Munich and made official in the meeting held in Rome between the Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. The central themes of the meeting were energy security, energy transition (hydrogen) and the expansion of gas pipeline networks in Europe: “Strengthening cooperation for the diversification of energy supplies is very important to me. Expanding supply networks in Europe will benefit us all and will certainly increase energy security. For this reason, I am delighted that we have agreed to continue work on a new pipeline to transport natural gas and hydrogen between Italy and Germany” said the German Chancellor during the press conference.

“On the energy front, we agree on the need to ensure the diversification of supply sources. On this front we are working together with the EU Commission in support of the SoutH2 Corridor project, which will connect the green hydrogen flows of Italy, Germany and Austria in the future”3, responded in the same press conference Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni at Palazzo Chigi.

Since last January, in fact, Italy has taken concrete steps on the issues discussed in the press conference mentioned above. Giorgia Meloni, during her official visit to Algeria in the first month of 2023, had proposed hydrogen in addition to gas as a response to the energy crisis and had spoken of transforming Italy into an energy distribution point: “It is to achieve an increase in gas exports from Algeria to Italy and the EU, the construction of a new hydrogen pipeline, the possibility of making liquefied gas, in short, an energy mix mechanism that we identify as a possible solution to the current crisis. […] We set ourselves the legislative horizon of making Italy a sort of energy distribution hub.”

The goal that Prime Minister Meloni has set is actually inspired by a figure that entered politics long before her: Enrico Mattei (see Mattei Plan), former deputy and founder of ENI, who lived between 1906 and 1962. These initiatives, according to many, have a tendency to transcend governments and become state policy, as the journalist Angelo Bruscino argues: “Furthermore, it is a project not so much of the government, but of the country system, as demonstrated, for example, by the joint press conference last July by Sergio Mattarella in Maputo with the president of Mozambique Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, which concerned natural gas liquefied Mozambique, another player to rely on for the new energy bouquet.”

In addition to President Sergio Mattarella’s approach, the words spoken during the official visit to Algeria by Claudio Descalz, the CEO of the Italian multinational ENI (one of the largest oil and energy companies in the world) seem to confirm this thesis: “We need a strategic plan, a shared vision that does not depend on the color of the governments that alternate at the helm of the country but exclusively on the national interest.”

Many European countries look with interest at this vision of Italy. But above all, it is Germany. The German government, which was in serious trouble with the deactivation of the Nord Stream pipeline, was closely following Rome’s talks with North African countries after it was completely deprived of Russian gas, and started to look warmly to the project of Italy to become an energy distribution point towards Europe. “From an economic point of view, the cut in supplies of large quantities of gas from Russia, caused by the conflict, has generated, compared to the time needed to bring a serious ecological transition into full swing without causing damage to the economy and the weaker social classes, the need to resort to the fossil produced by other possible suppliers. The recourse to the Mediterranean is obvious, and even more obvious, given the close interconnection between the two industrial economies, is the prospect of a rapprochement between Germany and Italy” observes the writer Leonardo Giordano.

The journalist Sergio Giraldo reminds us that Germany, which previously “had worked to exclude Italy from its supply routes”, now must have thought that it could benefit from the new conditions created through Italy. And thus it has turned its eyes to North Africa and to the energy that will come from there: gas and hydrogen. It seems like Berlin doesn’t have a choice anyway as it needs both fossil fuels and renewable energy that can be used in heavy industry in line with the promises made to the public: “Now, however, it is clear that the corridor from the south is the only one that can also be used for northern Europe.”

So, in addition to the political, geopolitical and economic reasons that drive Europe to find new markets for fossil fuels, also the need for a stronger ally like green hydrogen – as existing renewable sources of green energy (solar, wind etc.) do not appear to be able to meet the needs of the western world either today or in the foreseeable future – has led Meloni and Scholz to announce the SoutH2 Corridor project.

The hydrogen bridge

The SoutH2 Corridor was initiated by Austria, Germany and Italy to have a southern gas and hydrogen bridge in the European Union: A 3,300 km pipeline that will connect North Africa to the European continent. The pipeline will start from Algeria and will pass through Tunisia, where the wind and solar radiation favor the electrolysis process from which hydrogen is obtained, it will pass under the Sicilian channel, up to the Italian entry point of Mazara del Vallo (Sicily).

The SoutH2 Corridor is part of the de-carbonization goal of the Fit for 55: to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. Therefore it is assumed that the work will be ready in the same year.

It will transport renewable hydrogen through a large part of the existing infrastructure, reusing 73% of the network already in operation, while 27% will be new pipes, ready to transport both gas and hydrogen, so “this double value makes the work precious.” The Italian part will be made up of 2,300 km of network (3,300 km in total).

According to forecasts, the project will contribute to the achievement of the European de-carbonization objectives by transporting renewable hydrogen from North Africa (4 million tons per year of green hydrogen, or rather renewable).

- It will offer a concrete energy solution to the production of industries located between Northern Italy, Austria and Southern Germany that the latter two are far from coastal areas or that do not have renewable energy resources at competitive costs for the transition.

- It will guarantee a quantity of hydrogen sufficient to cover over 20% of the production target set for 2030.

- It will help improve the autonomy of Italy, Germany and Austria in the energy field.

- It will have easy access to EU funds being under the umbrella of sustainability (see RepowerEU).

- It will partially satisfy domestic demand for renewable hydrogen.

And on the other hand, the SoutH2 Corridor reports that the designation of Italy as a gas hub for Europe is increasingly in the facts: With a relatively small investment (3.2 billion) Italy will have a strategic role for the whole of Europe, ensuring the transit of gas and hydrogen for northern parts of the Old Continent.

Reasoning about hydrogen

It appears that renewable energies, as we have stated previously, will not be sufficient for the ever increasing energy demand, either today or tomorrow. While they appear to be efficient at providing electricity, they are not sufficient to power heavy industries such as steelmaking.

The hope of these sectors, which will eventually have to give up fossil fuels or drastically reduce their use and fill their void with truly green energy, would rest on green hydrogen, which some also call the “the champagne of the energy transition.” And they call it “the champagne” for a good reason: high quality for a higher price.

Hydrogen on earth is very abundant but not in a free state, and the most immediate source from which to obtain it is water through electrolysis. If the energy needed to operate this instrument comes from fossil fuels, the product is gray hydrogen; it is blue if the CO2 is captured, stored or reused (in any case these are all procedures that increase costs); and green if energy without greenhouse gas emissions comes into play, or rather energy obtained from renewable sources, such as solar, wind or hydroelectric energy. This is the most expensive process for obtaining energy from hydrogen.

Saul Griffith, a prominent inventor in renewable energy who started his career at an Australian steel mill, “does not see a big role for green hydrogen” according to New York Times. To replace fossil fuels, he writes, “the electricity you use to make it would have to be ridiculously cheap (but it is not). And if you have that, why use it to make hydrogen?” Griffith emphasizes that hydrogen “will not be the one to save the world.”

Apart from the enthusiasm of politicians, environmentalists, investors in the matter, there are skeptics like Mr. Griffith who asks the question of the usefulness of hydrogen. Until now, in fact, what demotivated investments in green hydrogen was above all the price on the market, which is still too little competitive with that of oil.

Let’s take Algeria as an example, from where Italy wants to transport hydrogen to Europe through the SoutH2 Corridor. The production of green hydrogen in the North African country is still in its infancy, whereby the prices are incomparably higher than fossil fuels, reports journalist Angelo Bruscino: “In Algeria, the development of hydrogen is at zero year. Above all what Italy needs, green hydrogen, produced with the use of sustainable sources, such as photovoltaic panels or wind power. On the other hand, the green hydrogen produced in Algeria now costs 11 times more than fossil gas per thermal unit.”

Another major problem Europe faces is the availability of space. In order to be able to produce green hydrogen in large quantities, immense empty or abandoned areas are needed with favorable atmospheric and geographical conditions. For example, Italy is trying to promote the hydrogen valleys for the production of green hydrogen on its soil. However, the country does not have enough available space to devote to wind and solar processing to meet the need for enough green hydrogen. And the atmospheric and geographical conditions necessary for the green hydrogen process are much more favorable in the African continent.

For all these reasons Leonardo Setti, the professor of renewable energies at the University of Bologna, makes clear that “the only possible strategy would be to import green hydrogen in large quantities from countries that we would have to ‘colonize’ to produce the necessary renewables, such as Libya and Algeria, bringing it to Italy via hydrogen pipelines or from Chile and Morocco by ship and regasification terminals.” And again according to the professor, green hydrogen is only convenient for oil and gas multinationals who need to de-carbonize the production cycle due to the new regulations and above all because sooner or later fossil fuels will be scarce: “Hydrogen is the green carrier of oil companies and not the energy communities.”

Marco Alverà, former CEO of a large multinational SNAM (an energy infrastructure company) focuses on the transport solution from non-EU countries, the journalist Amelia Vescovi tells us: “If in fact in Europe we fail to obtain enough renewable energy to obtain green hydrogen, not being able to carpet all our meadows, hills and coasts with panels and wind turbines, we can delegate production to those who have large spaces capable of hosting titanic solar parks and wind turbines, such as the prairies and deserts of Africa and Asia, to then convey the hydrogen in the gas pipelines arriving in our south. According to Alverà, rather than making it at home, it could therefore be more convenient to buy green hydrogen from the countries that have so far supplied us with oil and gas.”

Despite this, Brussels has the goal of producing 10 million tons of green hydrogen by 2030 in the European Union. And to make the challenge even more difficult, the European Commission is asking that by 2028 green hydrogen be generated only from newly installed renewable sources, therefore not from already existing solar panels and wind turbines. Today, around 10 million tons of hydrogen are produced in the EU territory but mostly from burning coal or gas so it’s gray hydrogen not the clean, green one. This means that within the next seven years the European Union must take giant steps to meet expectations.

And again Mr. Alverà – according to what we read in the pages of Andkronos – claimed in 2020 that “it is possible to glimpse a scenario in which a ‘turning point’ for hydrogen is reached at the price of 2 dollars per kilo, which in just five years it could be competitive with oil and without subsidies. The challenges for the definitive affirmation of green hydrogen (the one produced using electricity from renewable sources) foresee the improvement of its reputation and perception of safety; make the supply infrastructure capillary; reduce costs.”

Three years after this article, in 2023, the cost of green hydrogen is around $5 per kilo. The cost has a tendency to decrease over the years but it does not seem to be able to satisfy the forecasts of Alvera’ or those of the US Department of Energy which announced in March 2023 that the cost of green hydrogen will be around 1.50 – $2 per kg by 2035 and so “this forecast admitted that the previously stated goal of reducing the cost of clean H2 to $1/kg by 2031 is unlikely to be met.”

Is the hydrogen age about to begin? Whether it will become profitable in the face of fossil fuels and nuclear energy. What is certain is that billions of dollars are being invested worldwide in green hydrogen, states are promulgating laws, pipelines and production plants are being built to create infrastructure, new methods are being sought to reduce prices and large multinationals are entering in non-EU countries where the conditions for producing green hydrogen are suitable.

It seems that in the coming years we will come more often across projects like SoutH2 Corridor.

Leave a Reply