By Irene Léon *

Guayana Esequibo refers to a territory and sea that England coveted since the 19th century. The United States later placed it at the axis of the Monroe Doctrine and is now deploying a joint attack with its corporations, seeking to legitimize a situation of ‘ accommodated events ‘ that has been intensified since 2015.

An air of bonanza has accompanied the projections of the Exxon Mobil corporation, which obtained nearly 414 billion dollars in 2022, unprecedented income in its history, 44.8 percent more than the previous year and a gigantic increase when compared to its 2020 crisis, when its losses put its place in the stock market in check. Likewise, with the help of this American corporation, it is said that Guyana could become “the country that produces the most barrels of oil per inhabitant in the world, surpassing Kuwait. In such a case, when measuring the per capita wealth of its 800 thousand inhabitants, it would become a rich country, since in 2021 its GDP increased by 57.8 percent and in 2022 by 37.2 percent.”

However, in both cases, the bonanza comes mainly from the oil and gas exploitation which that corporation and country have activated in the controversial Esequibo region and even in Venezuelan waters.

This is an incursion is various forms, but with the invariable modality of “licenses” granted by Guyana, mainly to the American corporation Exxon Mobil, but also to Chevron, which also registers important income from this attack. Other corporations, such as the Spanish Repsol or the British Tullow, report large returns from upstream projects in the Upper Essequibo.

With the facilities provided by economic liberalization, private corporations have multiplied their dividends. What’s more, in addition to the well-known ability of transnational corporations to avoid the taxation of countries, the latter end up ‘compensating’ them through additional exemptions in free zones, so that corporations recover their investment in less than 5 years and begin to receive net profits, generally up to 80 percent of the benefits, while the producing countries barely collect the balance.

In the case of Guyana, barely 25 percent of the benefits remain in the country and a ridiculous redistribution of that income is evident, to the point that in 2019, the country’s human development index was the lowest in South America. At the same time, the extreme poverty affects 35.1 percent of the population, while the emigration rate reaches 55 percent. Up to 80 percent of people with higher education live outside the country. Clearly, “the creation of a liberal, rules-based economic environment” and the surrender of Guyana’s sovereignty primarily benefits US corporations and other transnational companies.

Under these conditions, ExxonMobil has come to assume as its own the territorial dispute that Guyana maintains with Venezuela and also with Suriname, since in the first case, a sovereign energy policy forces the State to operate based on the common good and not on corporate interests. This explains the communicational, legal and political mobilization that positions the entelechy that Venezuela wants to confiscate up to two-thirds of Guyanese territory.

Things have gone so far in the positioning of that story, that Guyana has gone to the International Court of Justice -ICJ-, to distance itself from the recognition of the existing border controversy and avoid the imperative of consent of both parties to outline the mechanisms of resolution, as stated in the Geneva Agreement. On the contrary Guyana supports the validity of the ‘Paris Award’ (1899), promoted by William McKinley, American president of the time, without the participation of Venezuela. Even more, Guyana tried to get the ICJ to interfere in Venezuelan internal politics and suspend the popular consultation that that country has called for the people to speak out on this problem, the ICJ did not do so, which constitutes a gain for sovereignty.

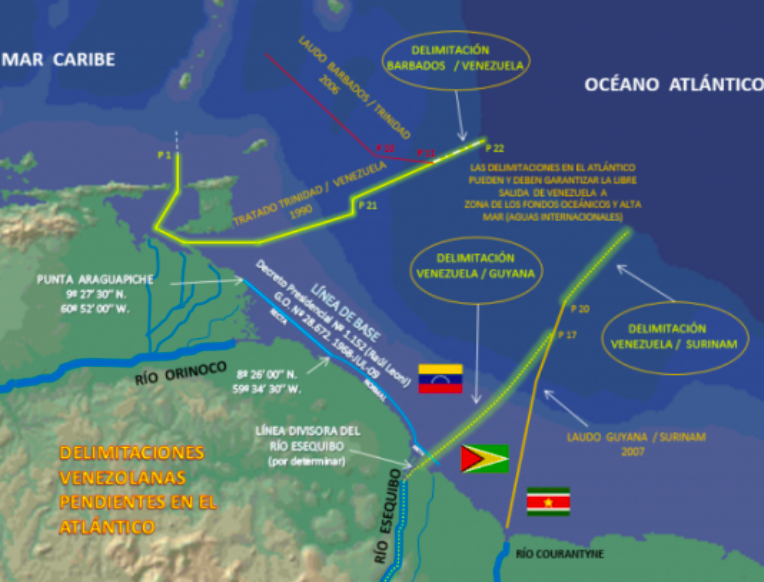

For its part, Venezuela argues that this is not only a matter of national and energy sovereignty but also a problem that concerns regional geopolitics, since it directly involves the attempt to make corporate interests prevail over the historical certification of a State. According to the Venezuelan president, Nicolas Maduro, “…more than Guyana, it is Exxon Mobil and the Southern Command that intend to take over the sea that belongs to Venezuela,” hence his call for dialogue with the neighboring country.

Exxon Mobil, an emblematic corporation of the United States, with its eyes set on reserves of some 11,000 million barrels of oil, abundant gas and ecosystems with high projection for the production of clean energy, has assumed as its own the strategy of judicialization that has undertaken “Guyana”. This proven, among other elements, by the corporation’s payment of some 15 million dollars for the legal defense of Guyana.

It is a case of regional interest, among others, because it highlights the scenarios of dispute between the thesis of corporate power: the “international rules-based order” versus international legislation and historical legitimacy, on which Venezuela bases its defense. The United States, – sorry Guyana, is taking this decision to a scenario of fait accompli and not to the resolution of international law, knowing that in the so-called arbitration courts, which are instances created by corporations to coax the States, the corporations win 90% of the time. According to the Venezuelan historian Omar Hurtado, in 1899 the arbitration was carried out between powers, without Venezuela. And without Venezuela, the Paris Award granted Great Britain (now Guyana) 90% of the disputed territory, without the concurrence of evidentiary legal elements.

Latin America as the epicenter of a “new” geopolicts of oil

Specialized business projections speak of a new oil geopolitics for 2028, at the top of which are: Brazil (Pre-Salt), Guyana (Esequibo) and Argentina (Vaca Muerta), in that order, while predicting a relegation of Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia, citing the decrease in their production, as well as management through public companies committed to the national economy and not to a stateless transnationalization for the benefit of corporations. In all cases, the epicenter of this oil prospect is Latin America and the Caribbean.

The historian Pedro Calzadilla interrelates the Paris arbitration award (1899) with the emergence of the concrete application of the Monroe doctrine (1823), while the formula of the arbitration award and the demonstration of American military force, not only marked the exclusion of Europe, but defined the hemispheric zone that the United States considers until now as its area of influence: “America for Americans.” This fact shows that with the Monroe Doctrine, the consolidation of the American geopolitical project to establish itself as hegemon began.

This approach to the event is very relevant now, when the maturation of the interrelation between corporate power and the military project of the United States is evident, which act as articulators of the project of restoration of capitalism. Precisely, in the case of Guayana Esequibo, Exxon Mobil enters the territorial dispute without mediation. In addition, the attack that began in 2015 coincides with an offensive of economic pressures, mainly the application of the unilateral coercive measures that the United States inflicts on Venezuela.

For 140 years, what is now called Exxon Mobil, has been built through a process of monopolistic mergers, in which the Standard Oil Company (1870) created by Rockefeller and associates appears. The history of this corporation is closely related to that of its home country, moreover, it emerges as a piece of American power. Steve Coll, author of ‘Private Empire: Exxon Mobil and the American Power’ (2013) emphasizes that these are two indivisible pieces of a whole: “It is a corporate State within the American State that has its own foreign policy rules” and a project to control energy resources through world scale.

This association is perceptible in different strategic episodes such as the military incursions committed by the United States, in Iraq for example and more broadly in the Middle East, ExxonMobil turned out to be the maximum supplier to the Pentagon (1999 – 2005). Also, in the energy projections that the North American country exhibits, this corporation appears even among the most important for the current and future management of clean energy, even if its field of specialty is the exploitation of fossil fuels. However, even in the context of the proposed energy transitions, it is estimated that the demand for crude oil has significant future economic projections. The IEA estimates that by 2028 global oil production will increase by 5.8 million barrels per day and that Latin America will supply a quarter of that.

Exxon Mobil is well known as the author of the most emblematic ecological disasters, for its denialist position on climate change and even for accusations of manipulating information about climate risks and affecting investors. But it has also been denounced for having a privileged relationship with the government, according to OMAL “The history of this oil corporation that is part of the North American Military-Industrial-Financial-Communication Complex, is a story that is loaded with dispossession, tax evasion, interference , attacks on the environment and systematic violations of international law, it is also closely linked to the State Department and the North American far-right sectors.” That is the profile of the environment of geoeconomic actors who maneuver to consummate a large-scale territorial appropriation in the Latin American and Caribbean region.

* Irene Léon is an Ecuadorian sociologist and expert on international politics specialized on Globalization and the right of communication. This article first appeared in TeleSURtv here. Translation from Spanish by UWI.

Leave a Reply