By Mehmet Enes Beşer

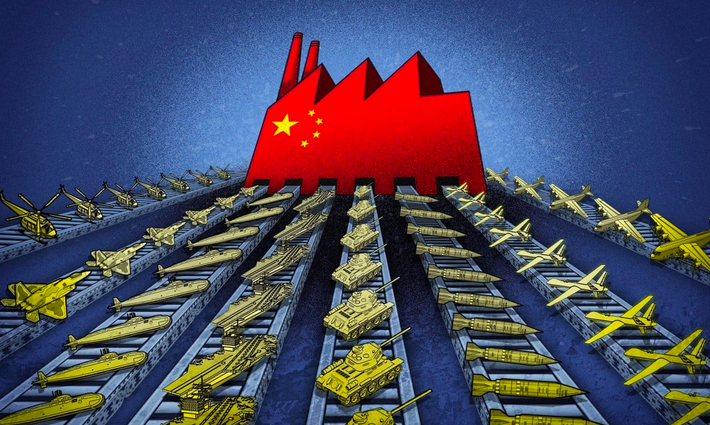

China’s rise as a world power has been most visibly articulated in terms of economic growth and technological development. But behind the waves of ports, highways, and 5G is a second power quietly remaking the contours of geopolitics: the military-industrial complex. No longer just an inland base of national defense, China’s state-connected defense industry has become a global strategic tool of influence—a fusion of industrial capacity, technological aspiration, and geostrategic objective. Its impact is felt beyond the projection of hard power. It is remaking trading flows, rewriting alliances, and making competitors as well as allies remake militarily. Historically, China’s defense industries had been afflicted with fragmentation, backwardness in terms of technology, and dependence on foreign components.

But there has been phenomenally transformative development over the last two decades. Spurred by a overall policy of civil-military integration (junmin ronghe) and aided by state planning, the capital has consolidated its defense industries into monster conglomerates—AVIC, NORINCO, and CETC among others—to cover civilian and military pursuits. Not only do they make advanced weapons platforms, but the corporations are also leading powers in high-tech fields such as AI, aeronautics, shipbuilding, and navigation satellites. Its dual-use character obscures the difference between commercial competition and strategic coercion. The stakes are gargantuan.

China’s military-industrial advancements allow it to exercise more assertive conduct from the periphery—from artificial island construction in the South China Sea to more frequent and routine incursions off the coast of Taiwan. This is not a deterrence phenomenon. It is a phenomenon of reshaping the status quo in Beijing’s interests, incrementally expanding spheres of influence through infrastructure backed by implicit military might. The PLA Navy expansion, for instance, cannot be separated from Belt and Road Initiative port investments in the Indian Ocean, where commercial facilities at Gwadar, Hambantota, and Djibouti are overshadowed by strategic rivals. As China infuses military interests into its global economic role, others are doing the same.

Japan has laid aside decades of post-war pacifist ambiguity, doubling defense spending and investing in networks of long-range strike. Australia has deepened defense cooperation with the U.S. and Britain in AUKUS, in reaction to China’s growing presence, to acquire nuclear-powered submarines. India, watching China’s military expansion along the Himalayas and the Indo-Pacific, is accelerating its own defense modernization and strengthening its strategic partnership with Western democracies. Even among China’s economic partners, defense-industrial considerations are tipping the balance.

Southeast Asian states, while significantly engaged in trade with China, are hedging against over-dependency by increasing defense spending and tilting towards security alignments with middle powers like Japan, South Korea, and France. In Africa, where Chinese arms deliveries have grown incrementally, governments are increasingly viewing Beijing as a development partner as well as a security interest—a twin role that raises China’s diplomatic leverage, especially in peacekeeping and counter-insurgency efforts. At the heart of this revolution is not merely arms production but an evolving pattern of strategic state capitalism.

China’s integration of the civilian and the military industries has the capacity for rapid innovation and rapid deployment. Artificial intelligence, quantum technology, hypersonic missiles, and space technology are all made with national-security priorities in mind, often obscuring the line between military doctrine and industrial policy. This model, while good, is transparent—causing greater stress to competitors who cannot quantify China’s effective capacity or intentions. Washington: It has responded with containment and accommodation. Export controls specially aim at semiconductors and AI chips as a way of decelerating China’s defense-tech convergence. NATO, previously a Euro-Atlantic alliance, now includes China among its strategic challenges. And the U.S. defense establishment is shifting its posture from counterterror to great power competition, with Indo-Pacific deterrence more in the foreground of planning and budgeting.

But China’s military-industrial complex also contradicts Western hypotheses about defense economics internationally. Whereas Western militaries are stereotypically despised for inefficiency and government procurement cycle dependence, China’s defense industries operate in the environment of long-term strategic tasks, vertically integrated production structures, and massive state-funded R&D endeavors. Scale, velocity, and strategic intensity can be achieved in this system, but at the cost of transparency and market competition.

Conclusion

China’s military-industrial complex is no longer an inward, domestic system of national defense. It is more a geopolitical strategy driver—concentrating technology, trade, and territorial ambition into one, evolutionary doctrine. Its implications are resonating far beyond the borders of East Asia, leading states to rethink defense postures, to pluralize loyalties, and to redefine their vision of what power in the 21st century really implies.

The globe is not faced with a traditional arms race. It is faced with a new paradigm—where productive power, cyber capabilities, and state-initiated initiative converge to blur the distinction between peace and menace, commerce and control. And as China increasingly deploys this paradigm—willingly or unintentionally—world geopolitics will not be defined by who possesses more tanks or vessels, but who is best able to marry industry, technology, and cause with maximal strategic discipline.

The age of silent change is gone. World order is now being determined in war rooms and factories. China knows this. The rest of the world is slowly catching up.

Cover graphic: Illustration by Henry Wong, South China Morning Post

Leave a Reply