By Mehmet Enes Beşer

China’s rise as a world power has unleashed a diaspora spirit of pride throughout ethnic Chinese groups around the world. It can be sensed in Malaysia, which possesses one of Southeast Asia’s largest and most politically powerful Chinese communities, to be precise. China’s economic rise, global economic power, and growing diplomatic assertiveness are met with a mix of admiration and awe by Chinese Malaysians. To others, Beijing’s rise represents challenging Western hegemonic discourse for decades and offers a new sense of ethnic pride.

But this pride exists alongside an assiduously maintained cultural distance. Chinese Malaysians, even as ethnically connected to China, have formed an identity infinitely more hybrid, local, and stratified than any forced attribution of Chineseness ever can imply. Their connection to China is affective and not one-way; related and not in thrall. What emerges instead is a particular diaspora state—one sensitive to ancestral recall but insistent on a here and now determined by Malaysian fact.

This tension has its roots in history. The majority of Chinese Malaysians trace their roots to immigrants from southern Chinese who came to Malaysia in the 19th and early 20th century, long before the People’s Republic of China was established. The migrants were largely Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, and Teochew speakers and introduced a multi-faceted heritage of dialects, customs, and clan affiliations. They became embedded in Malayan economic and social life over time—building schools, temples, trade associations, and newspapers to meet their distinctive communal needs. This cultural infrastructure assisted the Chinese Malaysian community in maintaining ethnic solidarity while creating a distinctive Southeast Asian identity.

The Cold War decades further consolidated the divergence. While China made revolutions in circles, Maoism, and economic reform, Chinese Malaysians grappled with their own set of problems—racial tension, affirmative action policies, and the problematic task of national integration in post-independent Malaysia. China was economically and politically distant for decades. Local Chinese identity did not coalesce as a referent to Beijing but as a working-through of the Malay-Muslim majority, the Indian community, and the boundaries and potential of Malaysian multiculturalism.

One of the principal sites for this identity making was education. The Malaysian Chinese vernacular school system and more specifically the Dong Zong chain of Chinese independent high schools became both a cultural badge of honor and a localization tool. When Mandarin was employed as the language of instruction, yet the curriculum itself was Malaysian civic reality-oriented, and the kids were more prone to speak Malay or a dialect at home rather than Standard Chinese, this generated Chinese Malaysians who could recognize Chinese cultural heritage but not that of automatic loyalty of the Chinese state.

And now, this ambivalent identity is articulated in Chinese Malaysians’ response to China’s ascendance. There is admiration for its success on the global stage and appreciation of shared cultural heritage, but suspicion of its authoritarianism, geopolitical ambitions, and pretensions to cultural leadership. The Hong Kong protests, Chinese handling of ethnic minorities, and South China Sea tensions all have different resonances in Malaysia, where Chinese Malaysians must prove themselves justifying themselves with their home patriotism not being equal to foreign sympathies.

Beijing has attempted, however, to activate overseas Chinese communities as assets in its global soft power outreach. Cultural centers, media contact, and education programs have attempted to establish an identity of pan-Chinesehood. But these most often fail to capture the complexity of diasporic identities. Malaysian Chinese are not aligning with the Chinese nation-state. Loyalty is to the Malaysian landscape, but Malaysian Chinese hold residues of Chinese culture.

The Malaysian state itself has helped produce this identity. Policies like the Bumiputera affirmative action program have mobilized and marginalized the Chinese people—urging them to construct autonomous institutions while still maintaining the call for more expansive political coalitions and civic participation. Along the way, Chinese Malaysians have emerged as economic leaders and cultural interlocutors—engaged in the project of belonging to the nation while pragmatically and tenaciously adjusting to minority status.

Over the last decades, there emerged a new Chinese Malaysian generation to speak this identity into being in new languages—more cosmopolitan, more multicultural, and more politicized. For this generation, China is a world actor to be acknowledged, rather than a homeland to be recalled. Theirs is less tied to ancestral remembrance than to the here-and-now reality of being Malaysian within a networked, unequal, and digitally mediated world.

Conclusion

Chinese Malaysians are at the intersection of a number of tides—national and ethnic pride, national citizenship, and international geopolitics. While they undoubtedly do take a genuine pride in China’s rise, they have not been absorbed into the identity of China. Instead, they have constructed a unique and durable cultural presence on the basis of Malaysia’s multicultural society and political culture.

This bifurcated consciousness of being civically Malaysian and culturally Chinese defies such simplistic tales of diaspora loyalty or transnational belonging. It insists that one acknowledge diaspora communities not as satellites of culture, but as independent societies in their own right with their own trajectory, concerns, and hopes.

In an increasingly polarized world of great power competition and identity politics, Chinese Malaysia’s lesson is one of balance: one can reminisce about heritage without abandoning autonomy, and connect to the global without forsaking the local. That, in large part, is indeed the true test of identity—not necessarily in the homeland one originated from, but in the ways, one wishes to belong.

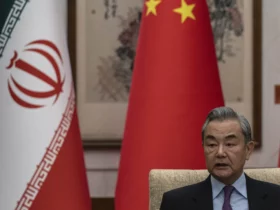

Cover graphic: South China Morning Post

Leave a Reply