By Mohamed Sabreen, from Cairo / Egypt

The Arab world is witnessing serious challenges represented by many explosive conflicts, whether in Palestine, Syria, Sudan, or Libya, amidst a state of changes in the balance of power in the region, and new threats against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s policy, which is difficult to predict. Some Western observers believe that American policy in the Middle East has witnessed successive failures over the past three decades, but the current strategic landscape provides new opportunities that Trump may exploit to formulate historic diplomatic agreements or ignite more crises. On the other hand, Arab experts do not have great hopes regarding Trump’s ability to achieve major accomplishments, especially in the Palestinian issue and the two-state solution. The region is also closely following the upheaval in Washington-Moscow relations, talk of a new Yalta, the “Syria for Ukraine” deal, and Putin’s announcement of his readiness to mediate between Washington and Tehran in the Iranian nuclear file, and even the countries of the region’s efforts to mediate between Trump and the leaders of Iran. Amidst all this, some in the region recall memories of the “American-Soviet détente” between Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, and their agreement on “military relaxation in the Middle East.” The late Egyptian President Anwar Sadat went to the October 1973 war, defying the wishes of Washington and Moscow. Despite the huge changes in the balances of the international and regional arena today compared to the seventies, the Arab world strongly feels the shadows of a “new agreement between Trump and Putin.” The Middle East region has begun to review and evaluate the opportunities and risks necessarily resulting from the region entering the shadows of a new Russian-American agreement, which does not enjoy consensus within Washington, European rejection, and cautious anticipation in the Arab world.

A Fragile Order in the Middle East

As the world and the region grapple with the consequences of Trump’s second term, Washington’s unstable policies have become a burden on the entire international community. “There is no place in the world where people feel this burden more strongly than in the Middle East,” says Taha Ezz Khan, director of the Ankara Research Institute, in Izvestia.

Now, the fragile order in the Middle East is under threat. Israel, which relies heavily on American security guarantees, will inevitably find itself in a difficult position as Washington moves away from “global engagement.”

Israel’s role is changing dramatically. The Jewish state is no longer seen as the central axis in the US-led regional order. Israel’s policy of openly denying any solution to the Palestinian issue has become unsustainable. The two-state solution, a process that has long been in the background, has once again become a defining factor for the region.

At the same time, we should not forget Syria, which is no longer just a battlefield for proxy conflicts between the United States, Russia, Iran and Israel. The Syrian revolution has not only led to the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, but also to the collapse of the long-standing regional order based on “managed instability.”

We are now witnessing an inevitable transition to a multipolar world. As the geopolitical map is being redrawn, Washington’s escalation of trade wars will force regional powers that have long been accustomed to a unipolar order to reconsider their economic partners.

In the face of changing dynamics, players who are able to adapt their strategies to the new reality are likely to gain greater influence in the region. The situation is similar outside the Middle East. What matters now is how quickly Europe, Russia, and China can play an active role in transforming this region. Now, there are signs of a new entente between Putin and Trump.

Syria versus Ukraine

Hicham Barjawi, a Moroccan researcher in international relations, sees in an article titled “Between Putin and Trump… Syria versus Ukraine,” the possibility of a deal between Washington and Moscow, citing the convergence of statements by Trump and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on the difficulty of intervening in Syria, explaining that Russia’s abandonment of Bashar al-Assad may be linked to gains in Ukraine and Eastern Europe.

He said that in the presence of an American president who is committed to the value of the national interest and opposes supranational institutions, such as Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin will not refrain from making meaningful concessions in the Middle East; as it is illogical for Moscow to abandon Bashar al-Assad in less than 24 hours, when it has fiercely defended him for 11 years, just like that, without compensation!

The counterpart lies in Ukraine, as Russia’s rapid abandonment of support for Bashar al-Assad, and the convergence of statements by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov about the difficulty of developing a plan to save Assad, and Donald Trump about the necessity of direct American non-interference in the recent Syrian events, are data that push towards the hypothesis of a deal between Washington and Moscow in which their future roles in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Africa and the Pacific are harmonious amid the state of political and economic impotence that Western Europe is experiencing.

The End of the Unipolar Era

In an article titled “The Unipolar Era is Over – What Will the United States Do?” in the National Interest newspaper, American writer Thomas Graham sees the unipolar era as over, and that the international system based on liberal rules, which the United States built and maintained in the years following World War II, is disintegrating at an accelerating pace. And that the United States needs to redefine its role in world affairs. What does that mean and what does it require? After a period of friendliness following the end of the Cold War, competition between the great powers has returned strongly, and the United States finds itself facing two major powers, China and Russia. At the same time, smaller powers are drawing closer to one or more members of this triad. Global power and dynamism are flowing away from the Euro-Atlantic community, the core of the liberal order. Despite the United States’ resistance to this idea, the world is moving toward illiberal multipolarity.

The United States has faced a multipolar world before, but it has never actively engaged as a pole of power. From its independence until the end of the nineteenth century, it exploited European rivalries to advance its interests in Europe without getting involved in European affairs and without engaging in multipolar competition. After the end of the Cold War, the world became unipolar, allowing the United States to lead the world on the basis of the liberal order that supports American primacy in the future. But how will the United States respond to the emerging multipolarity?

There are two schools of thought today about this challenge: one calls for a retreat, and for the United States to reduce its involvement; the other calls for restoring order and formulating a bipolar framework as the basis for engagement. But neither school aims to put the United States in a position to actively participate in a truly multipolar world.

Constraining China and Preserving Russia

The task of shaping a multipolar order is to recognize the four potential great powers—Russia, China, India, and Europe—and to identify the challenges each poses.

The United States is constraining China’s geopolitical ambitions, especially in the technology sector, to ensure its supremacy. The United States must control its mounting debt problem, raise stagnant educational and health standards, strengthen its ecosystem, and overcome its sharp political polarization to prepare itself for the coming intense competition with China.

At the same time, recognizing Russia as a great power is a fundamental element of Russian national identity. But preserving Russia as a great power requires confronting Russia’s growing embrace of China as a result of Western sanctions. The United States cannot tear apart this current strategic alliance between the two countries, but it can soften it by easing sanctions on Russia so that Russian and Western companies can cooperate in Central Asia and the Arctic. This in turn reduces China’s growing influence in both regions. The immediate goal is not to decouple Russia from China, but to ensure that any deals Russia makes with China, whether diplomatic or commercial, are not as favorable to China as they are now. Europe has all the economic and technological capabilities to become a great power, but it lacks the political will and cohesion. Since the Cold War, European countries have allowed their defense capabilities to atrophy in order to deepen social and economic well-being and rely on the United States for security. But now they must assume their great-power responsibilities to deal with security emergencies.

Skillfully Manipulating Multipolarity

Success in a multipolar system will require Washington to rethink its behavior. This requires recognizing that great powers have strategic autonomy, pursuing their own interests whether they are compatible with or in conflict with those of the United States.

The United States must recognize the limits of its power and prioritize the defense of its vital interests. In this emerging multipolar world, it will not be able to dominate the world or bend other countries to its will. It must therefore demonstrate leadership by integrating divergent and competing interests to its advantage. In other words, it must skillfully manipulate multipolarity.

Is the Gulf mediating?

In the midst of all this, the region has witnessed intensive movements towards mediation between Washington and Tehran, and while Iran excels in threatening statements, it is moving in parallel with them on the path of diplomacy. Therefore, the visit of the Emir of Qatar to Tehran may come within the framework of Iran’s attempt to employ its developing relationship with the Gulf states in order to mediate with the Trump administration, and it may have done or will do the same with Riyadh, as it seeks to benefit from the reconciliation agreement between it and Saudi Arabia by pushing it to convey messages through it to Washington. The Emir of Qatar visited Tehran and met with both the Iranian Supreme Leader and President. The visit is important because it comes amid challenges facing the region that require mediation in files to avoid any escalation. During the visit, Khamenei did not miss the opportunity to blame Qatar for the Iranian funds frozen by American order since the prisoner exchange deal between Tehran and Washington in 2023.

Iran has diverse relations with the Gulf states, ranging from competition to friendship and neutral countries. Relations with Doha have been strengthened due to Qatari interests and the ambition of its leadership to play a mediating role in the region. Qatar has enjoyed a closer relationship with Iran than the Gulf Cooperation Council states, in addition to strengthening economic relations regarding the joint offshore gas field between them, which creates enormous economic potential for the two countries.

From here, it becomes clear how Iran has found a suitable opportunity to be able to weave strong relations with some Gulf states, and it is now working to exploit those relations in order for the Gulf states to continue to play the role of mediator between Tehran and Washington.

On the other hand, an Iranian official stated that there should be a direct dialogue between Iran and Washington, as the Trump era is not far from indirect mediations similar to the mediations of the Sultanate of Oman, and it was indicated at the time that Tehran might prefer other mediations away from Oman, such as Switzerland.

But the visit of the Emir of Qatar now might raise the possibility of the visit’s goal of mediating direct talks between Iran and Trump, especially since Tehran is waiting for the moment of negotiations with the US President, which both parties excel at, the bazaar merchants and the dealmaker, so Iran is trying to weave the path of negotiations with Trump and resorted to the Emir of Qatar to mediate at a time when Trump signed the memorandum to implement the maximum pressure policies, in addition to imposing sanctions on parties linked to the oil sector, and Iran fears returning to selling about 300 thousand barrels per day instead of the current 700 thousand barrels.

While US intelligence reports emerged about Benjamin Netanyahu’s intentions to push Trump to support his attack on Iranian facilities, Tehran clarified the paths available to it in the wake of the attacks, including that it would respond to Israel by launching stronger missiles, and that it would work to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, in addition to changing its nuclear doctrine from peaceful to military.

The Saudi Role

In return, the Kingdom repositioned itself strategically from the leader of the Arab coalition, “partner of Washington”, to a regional power that adopts positive strategic neutrality, i.e. adopting relations with all axes and major countries in parallel. The Saudi leadership paved a special path through which it re-introduced to the great powers that it is a country that decides its international policies according to its supreme national interests. The Kingdom signed a heavy contract to purchase weapons and equipment from the United States, putting enormous pressure on American companies to protect it, which forced an adjustment in the administration’s position.

Many Arab writers have written for years about the inevitability of passing through an American-Russian agreement to end the Ukrainian war, and nothing else will end the military confrontation between the two warring parties. It has become clear that without a strong and decisive American role in stopping the clash, there will be no ceasefire or cessation of military operations. Now the way is paved for negotiations after the Biden administration tried to win the sanctions war on Moscow to impose conditions for ending the war, the most important of which is a comprehensive withdrawal from all Ukrainian territories and the Crimean Peninsula, forcing Moscow to pay large compensations, and committing to a certain price for oil exports, that is, in general, “taming” the Russian Federation. The Biden administration generalized this policy to its allies in Europe and the world, so the war lasted a long time.

Iran and Russian Mediation

In a remarkable development, Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to mediate between Iran and the United States in nuclear weapons talks, the state-run Zvezda TV channel reported on Tuesday, citing Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

Earlier on Tuesday, Bloomberg reported that Russia had agreed to help the Trump administration communicate with Iran on various issues, including Tehran’s nuclear program and its support for anti-US proxies in the Middle East.

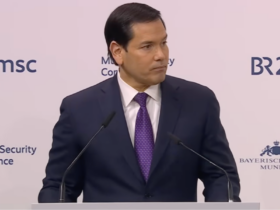

At the same time, Sergei Lavrov visited Tehran a week after the mini-summit in Riyadh between US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Russia to agree on the agenda for the upcoming presidential summit between US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, with the Ukrainian issue at the top of its priorities.

The Russian side in these negotiations does not hide the wide range of topics that will be placed on the table of the upcoming meeting between the two presidents, including the Iranian nuclear program crisis and the security and political stability of the Middle East region in light of the new equations imposed by the developments witnessed in this region.

Informed sources reported that Lavrov had brought a proposal for mediation between the United States and Iran, although both parties insisted on denying it or not talking about it, especially since the Iranian nuclear crisis was the subject of discussion and exchange of views between Presidents Trump and Putin in their first phone call, in addition to this issue occupying a space in the discussion during the mini-summit between the foreign ministers of the two countries in Riyadh.

It is expected that the Iranian leadership, through the government and its diplomatic administration, will deal with the Russian mediation initiative with great positivity, and will carefully and accurately read the transformations taking place in the relationship between the Russian and American parties and what they are trying to do to build a balance in the political and security equations and common interests between them and the reflection of this on the countries of the region, specifically Iran. Accordingly, the Iranian regime and its decision-making system may have to redefine its political and security behavior at the regional and international levels in light of the new equations.

The Russian initiative towards Tehran may be a Russian attempt to reassure the Iranian ally that it has no intention of circumventing it and abandoning it, meaning that Moscow seeks to send a message to Tehran by placing it in the atmosphere of the negotiations and talks it held with the American side, that it will not resort to concluding a deal with Washington at its expense and that the gains it will achieve in Ukraine will be in exchange for abandoning it in its crisis with Washington. Despite the gains that Moscow will achieve from the rapprochement between it and Washington on the Ukrainian issue and obtaining guarantees that Kiev will not be annexed to “NATO” and what this means in terms of removing the threat from the geostrategic and geopolitical depth of Russia, it still needs to deepen its relations and alliances with the Iranian state as a result of the great overlap in many international and regional interests that extend over an area starting from the Caucasus, passing through Central Asia and reaching the Middle East.

Separately, Putin’s foreign policy adviser Yuri Ushakov said relations with Iran were one of the topics discussed in recent Russian-US talks in the Saudi capital Riyadh, and that the two sides agreed to hold separate talks on the issue.

This development comes after Trump made a major shift in US policy, adopting a more conciliatory stance towards Russia, which made Western allies concerned about his attempt to mediate an end to the three-year Russia-Ukraine war.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that “Iran is a partner and ally of Russia and Moscow will continue to develop relations with it.”

“President Putin believes and is convinced that the problem of the Iranian nuclear file should be solved only by peaceful means,” he said. “Of course, Russia, as an ally of Iran, will do everything possible to facilitate a peaceful solution to the problem.”

The Middle East region is a focal point in the common interests between Russia and America on the one hand, and between Russia and Iran on the other hand, especially in light of the dramatic development witnessed in the Syrian arena and the collapse of its regime and the escape of Bashar al-Assad, in addition to the basic and most important file related to Israeli security, which constitutes a point of common ground between Moscow and Washington. This is an issue that the Russian side did not hesitate to clarify to the Iranian ally, and that it was one of the most important drivers that prompted the Russian leadership to take the decision to directly intervene in the Syrian crisis in 2015. Amid the development in the relationship between Moscow and Washington and the transition to a direct understanding of the crises pending between them and resolving their differences directly and without intermediaries or indirect messages, which may constitute an opportunity for the Iranian side to push for a Russian mediating role between it and the new American administration, especially with the growing Iranian belief that Moscow no longer needs to use its relationship with Iran as a bargaining chip and that many common interests impose on them (Russia and Iran) a new type of cooperation, in order to secure and protect these interests and stay away from the circles of danger and the possibility of new wars. The Russian position on the Iranian nuclear file constitutes a point of convergence with the American position on the issue of their refusal to allow Iran to possess nuclear weapons, which Iran is well aware of and knows as a result of the experiences it has had over the past decades of negotiations, and how Russia deals with these negotiations and Moscow’s role in supporting the international sanctions resolutions issued by the UN Security Council. The Russian initiative to open a new channel of communication between Tehran and Washington helps restore the heat to the negotiations, regardless of the titles taken by Lavrov’s visit to Tehran. This time, it may be an Iranian need, as it believes that it can reach clear and serious results, especially in betting on Moscow’s role in reducing the escalation that occurred in these negotiations as a result of the US President signing the executive memorandum and reactivating the policy of maximum pressure and severe economic sanctions, the latest of which is the series of sanctions on oil tankers and some activists in this sector that coincided with Lavrov’s visit. The Iranian bet on the Russian role may constitute an entry or exit for the position that went to suspending the negotiation efforts and refusing to continue them under the pressures that the White House began to impose, because the acceptance of the regime and the decision-making system to negotiate under these conditions sends a message that Iran acknowledges its weakness and the impact of its position on the losses that its regional project has suffered as a result of the strikes it received in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and to some extent in Iraq, and what things could go to in Yemen if it agrees to put its regional influence on the negotiating table alongside the nuclear file, and that the recognition and retreat in these two files means his acceptance of putting the file of his missile program on the negotiating table as well.

Last February, Trump resumed the “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran in an attempt to prevent Tehran from making a nuclear weapon. But he also said that he was open to reaching an agreement and was willing to talk to Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian. “The Trump administration will speak to our adversaries and allies alike, but from a position of strength to defend our national security,” White House National Security Council spokesman Brian Hughes said Tuesday, adding that the United States “will not tolerate Iran obtaining a nuclear weapon or supporting terrorism in the Middle East and around the world.” Iran has denied wanting to develop a nuclear weapon. However, the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency has warned that Iran is “significantly” accelerating its enrichment of uranium to 60 percent purity, close to the weapons-grade level of about 90 percent.

A Historic Opportunity

Writer Philip Gordon believes that Trump has great influence, but he must use it wisely. He says that for several decades the Middle East has been a graveyard for diplomatic ambitions, and at least since President George H.W. Bush left office in the wake of the Gulf War, American presidents have ended up leaving the region in a more dangerous state than when they took office, despite brief periods of optimism on many occasions.

Bill Clinton had high hopes for a historic peace agreement between the Israelis and Palestinians, and he managed to bring the two sides closer during the “Camp David Summit” in 2000, but his presidency ended with the collapse of the talks and the beginning of the bloody second intifada. After the September 11 attacks on the United States, George W. Bush succeeded in overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, under the slogan of transforming the region. But Bush soon found that this project had turned into a quagmire that claimed the lives of thousands of Americans and strengthened Iran’s influence. Barack Obama sought to seize the opportunity of the Arab Spring in 2011, and although he negotiated a nuclear deal with Iran, his aspirations for democracy and regional cooperation were dashed by the rise of ISIS in Iraq and the outbreak of a devastating civil war in Syria.

As for Donald Trump, during his first term, he believed that his withdrawal from the nuclear deal concluded by Obama and the killing of Qassem Soleimani would reduce the Iranian threat, but when he left office in 2021, Tehran was expanding its nuclear program and using its proxies to attack American forces and Iran’s neighbors. Finally, Joe Biden, who learned from previous failures, was keen to avoid grandiose ambitions, focusing on achieving stability in the region, but in his last year in office he found himself completely preoccupied with the repercussions of Hamas’s attacks on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the horrors of the war in Gaza that followed.

With such a history, it may seem naive to imagine that the Middle East today could play any role other than to cause trouble for the new president. If there is one thing that the past 30 years have proven, it is that the Middle East cannot be ignored at all, and it never ceases to surprise everyone, and no matter how bad the situation may seem, it may always get worse.

But Gordon acknowledges that despite the real problems and dangers facing the region, Trump is in fact inheriting a set of opportunities, and in some ways he may be well positioned to take advantage of them. “This is something I acknowledge even as one of Trump’s most vocal critics and a former national security adviser to Vice President Kamala Harris,” he says. “In addition to the new strategic landscape he inherits, his unpredictability may give him leverage in dealing with Iran, Israel, the Gulf states and others, and he may be able to push through Congress policies such as reaching a nuclear deal with Iran, something no Democratic president has been able to do.”

But Trump is also uniquely capable of exacerbating the Middle East’s problems, and he has already begun to do so with his decision to cut off vital U.S. aid to the region and his call for the deportation and seizure of Gaza. The fate of the Middle East over the next four years will depend largely on whether Trump can seize these strategic opportunities or squander them with his reckless impulses.

A New Deal

The first opportunity Trump inherited concerns Iran, which for decades has been at the heart of the Middle East’s problems. Today, Tehran appears weaker and more vulnerable than it has been since the Iranian revolution in 1979. Two of its most prominent proxies, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, have been militarily destroyed, and its arsenal of ballistic missiles, long a second line of defense alongside those proxies, has proven ineffective against Israeli air defenses backed by the United States and other regional powers. Syria, Iran’s main regional partner, is no longer ruled by its ally Bashar al-Assad but by an anti-Iran coalition that has deprived Tehran of its land bridge to Lebanon. Moreover, Iran’s air defenses proved so ineffective against Israeli air strikes in the fall of 2024 that Iran felt so weak that it refrained from even attempting to respond. At the same time, Iran’s economy, devastated by years of mismanagement, U.S. and international sanctions, and a period of low oil prices, is under enormous pressure, a situation that cannot serve as a basis for addressing new gaps in its defense and deterrence capabilities. Under these new circumstances, it is no surprise that Iranian leaders have begun to signal their openness to a new nuclear deal, because the alternatives to such an agreement are worse for Iran than ever. Indeed, President Masoud Pezeshkian was elected in 2024 on a platform of improving the economy, and the only possible way to achieve that goal is to conclude a diplomatic agreement with the United States and obtain sanctions relief. Although Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, a hardliner and longtime skeptic of talks, remains the ultimate decision-maker, he recognizes that Iran’s ability to deter military strikes against its nuclear program or its proxy energy infrastructure, ballistic missile strikes against Israel, and domestic air defenses has diminished significantly. Iranian leaders also recognize that the willingness of the United States and Israel to carry out offensive strikes has increased, especially with the increasing boldness of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the unpredictable Trump. Trump has expressed interest in a new deal, and the new strategic landscape could push Iran to make far greater concessions than previously envisioned. Among the concessions that were not possible in the past but could be today are strict limits on uranium enrichment levels, indefinite conditions, limits on ballistic missiles, and even limits on Iranian meddling in the region (especially since Iran’s proxies have already suffered significant setbacks).

A new deal could also include preventing Iran from enriching uranium domestically in exchange for access to an international fuel bank, a solution that could allow Tehran to argue that it has retained the right to use nuclear energy for civilian purposes, while allowing Trump and the Israeli government to claim that they have prevented Iran from controlling the enrichment process.

Despite these new strategic circumstances, there will still be limits to the concessions that Iran will make, and Trump may exaggerate his demands or even seek regime change in Tehran. But it should be clear that any agreement that reliably prevents Iran from developing a nuclear weapon and limits its regional influence will be attractive. Indeed, the combination of a weakened Iran and the increasingly credible threat of American force makes such an agreement more realistic than ever. If Trump can negotiate such an agreement, he will be able to boast that he got a “better deal” than the one Obama reached, and then sell it to Congress.

War and Peace

Trump’s second opportunity in the region is to end the war in Gaza, the biggest setback for peace and stability in the Middle East since the Iraq War, and then embark on the long process of stabilizing the “day after.” Since Hamas’s horrific attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Israeli response, the situation in Gaza has been an unbearable tragedy. But the ceasefire and prisoner exchange agreement reached by Hamas and Israel on January 15, after months of failed efforts and with the help of the incoming Trump team, offers a possible path to finally ending the war. After 15 months of unprecedented destruction and suffering, Israel has halted major military operations, Hamas has begun releasing hostages, and Gazans have begun to return to their neighborhoods.

But the first phase of the ceasefire is limited in time and scope and is not guaranteed to last, and moving to the second phase will require more difficult decisions about the release of prisoners (including Israeli soldiers), the release of prisoners held by Israel (including more militants), and ultimately the fate of Hamas. Meanwhile, the images of the emaciated Israeli hostages released on February 8 were a stark reminder to Israel that it must reach a deal on the second phase before more hostages die.

Hamas, too, must realize that ending the agreement would not be in its interest. Trump has threatened the movement with “hell” if it rejects the deal, and it knows that the “knights” it has been counting on, particularly Hezbollah and Iran, will not come to its rescue—one of the main reasons it agreed to the ceasefire and hostage exchange in the first place.

If Trump can help extend the Hamas-Israel agreement, or even prevent renewed fighting, he will have an opportunity to begin laying the foundations for stability in Gaza and the West Bank, and for a long-term peace agreement he has long sought between Israel and Saudi Arabia, an extension of the Abraham Accords he negotiated during his first term.

This historic vision requires not only an end to the war in Gaza, but also an Israeli commitment to a path to a Palestinian state. Such a commitment is certainly difficult to envision under the current Israeli government, but it may not be impossible under pressure from Trump, who will be in a unique position to influence Israel, especially if he sees it as a path to a Nobel Peace Prize.

There are also more realistic and limited goals that Trump could work to achieve if he is willing, such as demanding real reform of the Palestinian Authority as 89-year-old President Mahmoud Abbas nears the end of the scene; And convincing Israel to accept a role for the Palestinian Authority in managing Gaza after the war, which the remaining elements of Hamas may see as a less harmful option than continuing the destruction, and convincing the Gulf states, which are keen to maintain good relations with the US administration, to provide political support, reconstruction funds, and perhaps security forces to support the peace agreement.

But the problems and challenges will remain enormous even with this progress, but they will seem small and trivial compared to the destruction, divisions, and suffering that preceded the ceasefire agreement, and Trump will rightly take credit for that.

Seizing the opportunity

The Arab states, led by Egypt and Saudi Arabia, have repositioned themselves strategically from being leaders of the Arab coalition, “partners of Washington,” to a regional power that adopts positive strategic neutrality, that is, building relations with all major axes and countries in parallel. The Egyptian and Saudi leaderships have paved a special path through which they have re-introduced to the great powers that they are countries that decide their international policies according to their supreme national interests. The kingdom signed a heavy arms and equipment deal with the United States, putting enormous pressure on American companies to protect it, forcing a change in the administration’s position.

Riyadh signed extensive economic agreements with China, making it a partner that reached into the Gulf, and Beijing, in turn, oversaw a disengagement agreement between the kingdom and the Islamic Republic and a successful normalization. Riyadh strengthened its relations with Moscow and entered into trade agreements and arms deals with the Europeans, particularly France and Britain.

However, no one should underestimate the challenges and dangers that still loom across the Middle East. Weak and ineffective governments, deep religious, ethnic, and international rivalries, a multitude of bad actors, and the terrible consequences of the war in Gaza, which may not yet be over, will continue to impede progress toward peace and stability. At the same time, it would be a grave mistake to ignore the historic opportunities presented by the new strategic landscape, opportunities that seemed so far-fetched a year ago or even a few months ago. There is no doubt that Trump’s greatest ambition is to achieve what many of his predecessors failed to do. He may succeed in luring Russia away from China, and perhaps the Arab countries will be able to benefit from the successive developments and find themselves a place, and even an important role, in the climate of harmony and deals, especially with Iran. These may seem like daydreams for a region that has only known nightmares, but it is worth a try.

Leave a Reply