By Dr. Halim Gençoğlu (halim.gencoglu@wits.ac.za)

Recent discourse on social media platforms, including statements by high-profile figures such as Elon Musk, has invoked simplified narratives framing Western intervention as the sole liberator from global slavery while downplaying the Ottoman Empire’s humanitarian role and the enduring legacies of Western colonialism in Africa.

In a December 8, 2025, post on X (formerly Twitter), Elon Musk stated: “Children should be proud that Whites in the West ended slavery worldwide, which had existed for thousands of years.”

This assertion, echoed in supportive engagements with claims portraying slavery as a non-unique Western phenomenon, while emphasizing Ottoman enslavement of Europeans perpetuates a Eurocentric teleology that elides the West’s pivotal role in the transatlantic slave trade and colonial plunder. Such rhetoric risks reinscribing colonial apologetics, particularly when amplified by influential voices. This essay responds academically, integrating historical evidence and scholarly critique to dismantle these binaries. By recalling the Ottoman Empire’s refuge for Jewish exiles in 1492, documenting the repatriation of African ancestral remains, and invoking African intellectuals’ analyses of imperialism, it seeks to illuminate the West’s exploitative legacies. Addressed to Musk, it concludes with a call to transcend apartheid-influenced worldviews for a more inclusive historiography.

A Counterpoint to Western Persecution and Expansion

While Western narratives often position Europe as a beacon of progress, the late 15th century reveals stark contrasts. In 1492, the Alhambra Decree expelled Spain’s Jewish population, forcing an estimated 200,000 Sephardic Jews into perilous exile amid the Inquisition’s fervor. Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire responded not with rejection but with proactive rescue. He dispatched Admiral Kemal Reis with the Ottoman navy to evacuate refugees from Spanish ports, granting them citizenship and settlement rights across Ottoman territories, including Istanbul, Edirne, and Thessaloniki. Bayezid II famously remarked on King Ferdinand’s folly: “You venture to call Ferdinand a wise ruler, he who has impoverished his own country and enriched mine!” This act of multiculturalism—welcoming Jews as economic and cultural assets—contrasts sharply with contemporaneous Western endeavors.

That same year, Christopher Columbus’s voyages, sponsored by Spain and Portugal, inaugurated the Age of Exploration, which swiftly morphed into the African slave trade and colonial conquest. By the 16th century, Portuguese forts along West Africa’s Gold Coast facilitated the enslavement of millions, fueling European wealth accumulation. The Ottoman Empire, far from the “institutionalized sexual slavery” invoked in apologist tweets, integrated diverse populations under a millet system that afforded religious autonomy, including to enslaved Europeans who could often manumit or ascend socially.

Musk’s framing thus inverts historical agency, the Ottomans exemplified inclusive governance while the West systematized racialized bondage on an unprecedented scale.

Europe’s Colonial Corpse Collection

The physical toll of Western colonialism endures in Europe’s museums, where thousands of African human remains— skeletons, and organs—languish as “scientific” trophies. Acquired through grave-robbing, battlefield looting, and pseudoscientific expeditions during the 19th and 20th centuries, these collections embody epistemic violence, reducing Africans to objects of study under racial hierarchies. Recent repatriations signal a belated reckoning, yet they underscore the West’s delayed accountability.

In October 2025, the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow returned partial remains of six South African individuals—looted in the 19th and 20th centuries—to Iziko Museums under South Africa’s National Policy on Repatriation. This included plaster face-casts and artifacts from burial cairns, repatriated after ceremonies honoring ancestral dignity. Similarly, France repatriated the skull of Sakalava King Toera—beheaded by French colonial forces in 1897—to Madagascar in August 2025, alongside two warriors’ remains, under a 2023 law easing returns. In Tanzania, diaspora efforts target relics like the skull of Mangi Meli (hanged in 1905) and Majimaji War artifacts held in German institutions, with over 1,100 remains identified from Rwanda, Tanzania, and Kenya alone. These returns, while restorative, highlight how colonialism’s “scientific racism” persists: Germany’s Charité Museum holds 904 Rwandan skulls, acquired post-1904 genocide. Far from “ending” exploitation, Western institutions profited from it for centuries; repatriation is not benevolence but restitution.

Voices from Ngũgĩ, Mazrui, and Achebe

African scholars have long dissected Western imperialism’s mechanisms, revealing it as a continuum from slavery to neocolonial extraction. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, in Decolonising the Mind (1986), describes the “cultural bomb” of colonialism: “The biggest weapon wielded and daily unleashed by imperialism against that collective defiance is the cultural bomb. The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.” This linguistic and epistemic erasure, Ngũgĩ argues, perpetuated underdevelopment: “Imperialism and its comprador alliances in Africa can never develop the continent.” In colonial conquest, “language did to the mind what the sword did to the bodies of the colonised,” ensuring Africa’s resources enriched the metropole while fostering self-alienation.

Ali Mazrui, in The Africans: A Triple Heritage (1986), frames exploitation as technological arrogance: “Africa must modernize without Westernizing,” warning against emulating a system that “stole art treasures from Africa to decorate their houses and museums; in the twentieth century Europe is stealing the treasures of the mind.” Mazrui’s Tools of Exploitation episode critiques how European technology stymied Africa’s growth, inverting development: “Africa Developed the West,” via enslaved labor fueling industrial take-off, yet receiving only poverty’s extremes. He posits post-colonial instability as “cultures at war,” with Western cultural imperialism haunting Africa and the Muslim world.

Chinua Achebe, in Things Fall Apart (1958), illustrates colonialism’s rupture: “He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart,” capturing the insidious erosion of communal bonds by missionary deceit and administrative fiat. Achebe warns, “We cannot trample upon the humanity of others without devaluing our own,” a proverb underscoring reciprocal dehumanization. In “An Image of Africa” (1975), he indicts Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for racist othering, refusing Africans “human expression” and language, thus perpetuating colonial narratives that justify plunder. These thinkers collectively expose imperialism not as aberration but as foundational to Western modernity, demanding Africa’s reclaimed agency.

Transcending Apartheid’s Shadow

Elon Musk’s South African origins—born in 1971 to a wealthy family under apartheid—infuse his rhetoric with unresolved legacies. His grandfather, Joshua Haldeman, championed technocracy and apartheid, embodying white privilege’s neocolonial insularity: servants at beck and call, all-white schools like Pretoria Boys High. Though Musk’s father briefly joined the anti-apartheid Progressive Party, the family’s emerald mine and engineering ventures thrived on racial hierarchies. This “neocolonial life” shaped a worldview prizing individualism over systemic critique, evident in defenses of Western “progress.” To Musk: Shed these apartheid-era lenses, which normalize exploitation as exceptionalism. Engage decolonized scholarship; amplify African voices. Your platform can bridge divides, not widen them—true innovation lies in historical humility.

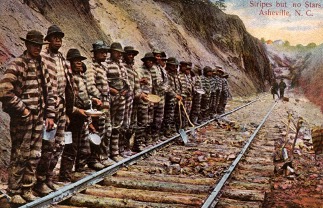

In 1865, the United States abolished slavery however this photo above was taken 50 years after slavery had officially ended.

Because until the 1960s, America forced unemployed Black people to work under various pretexts.

For example:

Being unemployed (“vagrancy”)

Walking aimlessly in the street

“Disrespecting” white people

Not carrying identification…

Courts would hand down sentences based on made-up charges—essentially punishing people for having “eyebrows above their eyes.”

Racist violence also prevented Black people from being able to object.

Perhaps the most striking part is that these people were converted to Christianity before being exploited in the name of Jesus’s justice.

Conclusion

This essay counters such views by highlighting the Ottoman Empire’s 1492 rescue of Sephardic Jews amid Spanish expulsion, juxtaposed against contemporaneous Western pursuits of African exploitation. It further examines the ongoing repatriation of African human remains from European museums, underscoring the material persistence of colonial violence. Drawing on insights from postcolonial scholars Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Ali Mazrui, and Chinua Achebe, the analysis critiques Western imperialism’s cultural and economic depredations. Finally, it urges a reevaluation of apartheid-era perspectives, rooted in Musk’s South African upbringing, to foster a more equitable global historical consciousness. This piece advocates for decolonized narratives that honor multifaceted histories without exceptionalist bias.

Musk’s provocations, while provocative, invite deeper inquiry. The Ottoman rescue, repatriated remains, and scholars’ indictments reveal a world where Western “endings” mask beginnings of profound injustice. By centering polyvocal histories, we honor dignity’s universality. Let this be a catalyst for dialogue, not division.

References

Achebe, C. (1958). Things Fall Apart. Heinemann.

Achebe, C. (1975). An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Mazrui, A. A. (1986). The Africans: A Triple Heritage. BBC/PBS.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. James Currey.

Shaw, S. J. (1991). The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. New York University Press.

Leave a Reply