By Şafak Erdem

When you look at the Mercator map head-on, Greenland appears to sit at the edge of the world, in a remote and marginal location.

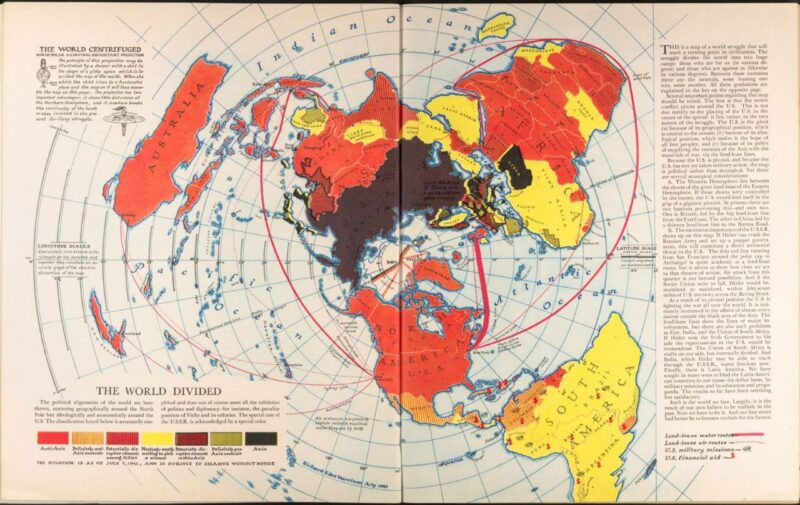

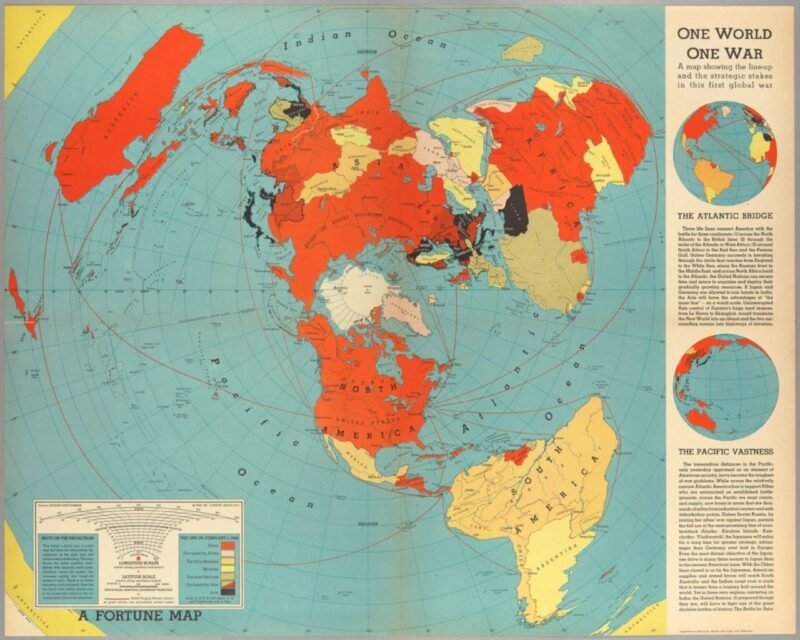

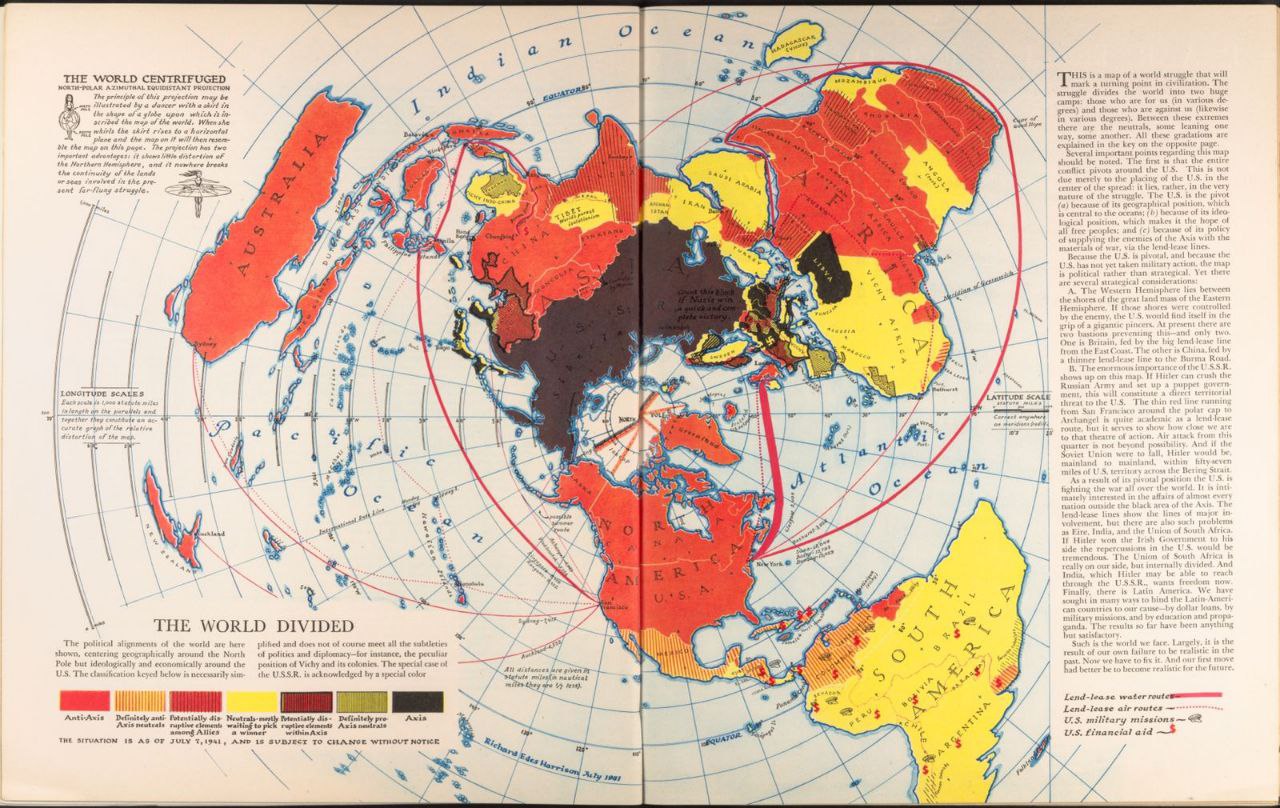

But take a look instead at Richard Edes Harrison’s maps “The Divided World” (published in 1941) and “One World One War” (published in 1942).

According to Cornell University Library’s Digital Collections, published in Fortune Magazine for August 1941, Harrison used a “then-unusual polar projection of ‘a world struggle that will mark a turning point in civilization,’ one that ‘divides the world into two huge camps.’ The United States had not entered the war, but Harrison designed the map to illustrate his point that ‘the entire conflict pivots around the U.S.’ because of its geographical position, its ideology of freedom, and its lend-lease support of the soon-to-be Allies.”

And the visual power of this map lies in “conveying the threat depends to a great degree on the size and menace of the black area of the Axis powers opposing the U.S. across the Pole.”

The second map, “One World One War,” sets aside certain differences that are not relevant for the purposes of this article, but ultimately reflects the same geopolitical thinking as the first.

Greenland for the US in the case of “partial withdrawal”

In his article titled “The geography of American power”, Michael Pezzullo, who served in Australia as former deputy secretary of defense and was secretary of home affairs until November 2023, builds on the geopolitical understanding embedded in these maps to propose a strategy of building a “sea-air barrier around Eurasia.”

At a time when a partial withdrawal of US power from different parts of the world is being debated, Pezzullo argues that “the US could comfortably withdraw from being the arbiter of the geopolitical fate of Eurasia and still enjoy a significant margin of security.” However, he adds that such a “locationally withdrawn US would have to be willing to accept the risk of the likely emergence of a hegemonic power in Eurasia.” Such a hegemonic power in Eurasia, he warns, “would become the leading global power. The goal of ‘making America great again’ would ring hollow in a world where a Eurasian hegemon dominated the heartland of the world, and where it could almost always deliver a ‘better deal’ to nations under its dominion—whether or not they were pleased with the terms of the deal.”

It is at this point that the strategy of a “sea-air barrier around Eurasia” comes into play. What Pezzullo calls “a modern sea-air barrier around Eurasia” can be described “as a series of strong points and areas of control that trace a line around these contested areas.” Such a barrier would enable the United States to “protect itself from approaching threats, and to more securely project power, whether in its own defence, or for broader purposes, such as protecting its allies.”

So where exactly would this sea-air barrier around Eurasia run? To see it, you really need to take a map in hand. Pezzullo explains:

“What line would such a sea-air barrier follow? Starting along the length of Canada’s Arctic coast, the line would run through Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands (which belong to Denmark), and Scotland, an area that forms the ‘GIUK Gap’ (to use its Cold War title). The US needs to control the GIUK Gap, and have access to Svalbard (which belongs to Norway), in order to contain the threat of Russian sea power in the Atlantic. From Britain, the line would run to Gibraltar and then to the British bases in Cyprus, so that the US could access the Mediterranean and protect the northern end of the Suez Canal. Through the canal, the line would run through the Red Sea to Diego Garcia, which is the most important US strategic base in the Indian Ocean, vital for projecting power into the Middle East, Central Asia, and eastern Africa.

From there the line would run to Cocos (Keeling) and Christmas Islands, which are Australian offshore territories. The line would then run through Exmouth, Darwin, and Townsville (which are all in Australia), up to Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, and then to Guam and other key US island territories in the Pacific, as well as the US state of Hawaii. Finally, the line would run along the Aleutian chain, and then through the US state of Alaska proper, and before linking with the starting point of the line, Canada’s Arctic coast.”

In the article, Pezzullo also refers to Nicholas J. Spykman. At the time Harrison was drawing these maps, Spykman was articulating similar geopolitical ideas in his 1944 book The Geography of Peace. Here’s what the book said about Greenland:

“We grant the new importance of Greenland and Alaska, but it is well that the reason for this should be understood. It lies in the military geography of the Baltic Sea and the Sea of Japan, not in the economic geography of the Arctic Ocean. We have been forced, during this war, to travel to Siberia and China by way of Alaska and to European Russia by way of Iceland and Murmansk because we have no other choice.

This fact means that the supply lines for goods and matériel to Russia and China have been of tremendous importance to our conduct of the war and much of our energy during the first two years had to be devoted to the securing of the routes that were available. To reach Russia, we had to gain access to the land-locked heartland region of the Eurasian Continent. We have seen how the topography of the Old World provides only a very few passages into this area and makes those few of definitely limited serviceability. The swift advances of Germany and Japan at the beginning of the war cut us off almost completely from the land approaches so that the Arctic and the Indian Oceans remained through the first years of fighting as the only routes continuously available. Their usefulness is, however, inevitably limited by climatic and topographical conditions.”

This is why the Arctic, and Greenland, the largest island in the Arctic (and in the world), was seen as so crucial to US geopolitics. There is nothing new in the importance that American geopolitical thinking has long attached to Greenland. Indeed, the US has long been present in Greenland.

How to make sense of Trump’s policy: a minimum of four components

So what has changed in recent years? How can Trump’s policy be grasped? I think at least four key components need to be considered.

First, as discussed above, is the longstanding importance that US geopolitical thinking has attached to Greenland. Bringing this thinking into 2026, if the US were to make partial withdrawals from certain regions, it would still seek geographies where it could project power to prevent the rise of other powers in the Eurasian “heartland.” Greenland could be seen as one such strategic location.

Russia and China: “Great power competition”

Second, Russia’s growing influence. Until recently, the Arctic region was often described as “high north, low tensions,” a relatively calm area in terms of inter-state relations. Recent developments, however, have turned that “low” into “high.”

The European Parliament writes in the report “Greenland: Caught in the Arctic geopolitical contest”:

“Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine resulted in the halting of most cooperation in the Arctic, reducing the channels for communication and further amplifying tensions. As a result, the Arctic, which was once known for attempted ‘low tension’ science and research cooperation efforts, is now the arena of fierce competition and mistrust, with Greenland at the center.”

Allison Brown, in her article “High North, Low Tension: A Primer on Multilateral Arctic Institutions and the Case for Expanded Military Governance and Security Capabilities”, explains the Arctic’s evolving position leading up to 2030 and how the US views it as part of a “battlefield for great power competition”:

“The Arctic will encounter numerous challenges and threats in the coming decades, with some already raising concerns. The region is expected to be fully open to public and commercial enterprises by 2030. The level of military activity in the Arctic, particularly in Europe’s far north, has been escalating amid rising global tensions between NATO members and Russia. U.S. policy regards the Arctic as a ‘battlefield for great power competition’ in which the interests of Russia and China as a ‘near Arctic state’ are at play.”

Imperialism without resources?

Third, the issue of rare earth elements, which also occupies a significant position in the discussion of Russia and China as powers with the potential to unseat the US in the “great power competition.”

The US Geological Survey (USGS), in its report “Statistics and information on the worldwide supply of, demand for, and flow of the mineral commodity group rare earths – scandium, yttrium, and the lanthanides,” highlights at least two striking facts:

- A very large proportion of rare earth elements are concentrated in just a few countries.

- Imperialist countries (or sometimes what we call “developed” countries) possess almost none of these rare earth elements.

China alone holds nearly half of the global total—48 percent—equivalent to 44 million tons. China is by far the leader.

Greenland, meanwhile, ranks eighth in the world for rare earth reserves, with 1.5 million tons, and is home to two deposits among the largest in the world: Kvanefjeld and Tanbreez. China also wields significant influence over Greenland’s rare earth resources.

Meredith Schwartz and Gracelin Baskaran, in their report “Greenland, Rare Earths, and Arctic Security,” outline the situation in rare earth resources:

“2025 was marked by multiple rounds of high-stakes negotiations following Chinese export controls on heavy REEs. Disruptions to these materials exposed Western automotive supply chains to shortages, delays, and pauses in production. President Trump has acted meaningfully to address these prescient supply chain concerns both through public-private partnerships, such as the equity deal with U.S. rare earth company MP Materials, and bilateral agreements with partners including Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Australia to further the development of rare earth capabilities outside of China. Deepening cooperation and commercial ties with mineral-rich countries is expected to be a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy in 2026.”

We read the situation in Greenland from the same report as follows:

“In 2018, China launched its Arctic policy, also known as the Polar Silk Road, in which it controversially referred to itself as a ‘Near-Arctic State.’ Over the past seven years, China has attempted to grow its footprint in the region through scientific research expeditions, infrastructure investments, and natural resource acquisitions. By most metrics, the strategy has failed to take off, as major projects continue to be blocked due to security concerns. But China’s continued interest in Greenland reflects the island’s geostrategic importance—and China’s global lead in rare earth mining and processing expertise keeps the U.S. adversary on the table as a potential future mining partner in Greenland.

(…)

In the last 10 years, China has ventured to invest in Greenland’s airports, an abandoned naval station, and a satellite ground station, but its ambitions have been largely stalled and curtailed by U.S. and Danish stakeholders. While China has yet to build a Polar Silk Road of geopolitical significance, China’s dominant position in rare earth separating and processing offers it an advantage in accessing Greenland’s rare earth resources via processing offtake agreements.”

Thus, for the US, a new situation is emerging in Greenland from two angles: the two rising powers from Eurasia, Russia and China, pose a potential challenge both geopolitically and in terms of resources, threatening to constrict the lifeblood of imperial leverage. What kind of imperialism is it if an empire, debating partial withdrawal, suffers serious losses in its geopolitical levers and falls far behind in rare earth elements, which are increasingly a foundational resource for contemporary capitalism?

A new type in the emperor-subject relation?

On top of all these developments, there is a US president whose words and actions have surprised many, a type they had not seen since 1945.

The “novelty” of Trump is captured with striking accuracy by Rasmus Mølgaard Mariager and Peter Fibiger Bang, both Professors of History at the Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen, in their January 12 article for the European Policy Center, “The Great Game of the Arctic, Denmark, Greenland and the US Empire.”

The authors describe the U.S. as an empire and Denmark as its subject, noting that the “emperor” approaches strategically important resources and security concerns with understanding in the face of the increased activity of both China and Russia in the Arctic. In such a “great game” dominated by great powers, they acknowledge that “tiny Denmark is clearly an inadequate guardian.”

Since the Cold War, Denmark has performed the role expected of a loyal subject: supporting the empire in wars such as the First Gulf War, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. “Denmark is a subordinate part of the global American empire and tried to honor the price of its alliance by providing auxiliary troops to the hegemon,” they note.

The subject, in turn, shows understanding of the emperor’s strategic concerns regarding the increased activity of China and Russia in the Arctic and fulfills its obligations in the empire’s wars. They further note that Denmark has executed these duties in Greenland since 1941, “granting US forces access to Greenland and the right to establish bases. Since then, Greenland has served as a strategic cornerstone in the American empire, with a significant permanent base, tying Denmark closely to the United States.”

But the “subject” also has a question: what does the subject get in return? The authors remind the emperor of his obligations: “Empires also depend on compromise and collaboration with local elites. In return for loyalty, subject-elites are offered protection by the military overlord.”

Otherwise, they warn, the “protective bargain” between emperor and subject could be called into question:

“This protective bargain has now been called into question. Empires have, as we say, relied on cooperation with local elites, but rising competition with Russia and China may have prompted the US to be less generous and renegotiate the terms of the arrangement. But in doing so, the new US administration seems to have forgotten that a successful hegemon will take care not to be the sole beneficiary of its empire, but safeguard its members. Threatening loyal allies is strategically self-defeating: Does the US administration believe that Europeans will continue to support the US’s global role if the US bullies its subjects – particularly when it need not do so?”

Another question criticizes the US for failing to fulfill its “duty”:

“Over the last decade, however, Russia and China have increased their military presence in the Arctic and the environs of Greenland. This raises an uncomfortable question: given its role as the primary security provider and effective hegemon in Greenland, is it not the United States, rather than Denmark, that has been negligent in its duties?”

Thus, the Danes and Europeans are asking what kind of emperor this is. The new relationship the emperor is building with his subjects is causing surprise. The Danish authors invoke James Burnham’s words from 1947, urging the emperor to consider that this new relationship is not the right one:

“If the United States wants to be first among nations, it will not succeed most easily by insisting that all other nations humble themselves before the Bald Eagle. On the contrary, it will do best if it demonstrates that other nations, through friendship with the United States, increase and guard their potential dignity and honor.”

A formulation

I believe it would not be wrong to propose the following formulation for what is happening in Greenland:

- An “Empire” considering partial withdrawal in the overall plan,

- Under conditions where, in the Empire’s geopolitical thinking, rival powers are rising in Eurasia’s heartland, which the Empire regards as one of its greatest threats,

- In a strategically critical island and its surroundings for accessing Eurasia’s heartland, where the influence and activity of rival powers are increasing,

- At a time when the Empire sees itself falling seriously behind in a resource that has become increasingly fundamental to contemporary capitalism, and on an island where the Empire believes it can partially recover its position in this regard,

- The Empire adopts a policy (perhaps a strategy) that goes beyond the post-1945 boundaries of the emperor–subject relationship

This formulation invites reflection on how the trajectory of the US as a leading imperialist power is reshaping, and could continue to reshape, its relationships with its subjects, allies, and “adversaries”.

Leave a Reply