BY TÜLİN UYGUR / STOCKHOLM

There has been a boost in internal and external criticism in Sweden as a result of the government’s ‘herd immunity’ strategy. The Swedish experiment is ongoing, but the results are already coming in, and things don’t look good.

On January 31, 2020, Sweden diagnosed its first coronavirus case, and immediately decided to follow a different path from other countries. High school, adult education institutions and universities were closed, and distance education replaced regular education, but kindergartens and primary schools were kept open. The Public Health Authority recommended working from home in all possible business sectors, and Industrial giants have stopped production and laid off their workers either temporarily or permanently. Sports competition and team training for adults were banned, but this ban was not instituted for children and young people born after 2002. The government recommended ceasing all unnecessary travel, but shopping malls, shops, restaurants, bars, coffee houses, gymnasiums, swimming pools and hairdressers were not closed. Addressing the nation on Swedish television on March 22nd, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven called for everyone to take responsibility for himself, humanity, and the country. Epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, the architect of Sweden’s strategy, announced two pillars of his strategy on March 24: to protect the elderly and patients by isolating and reducing contact between healthy and sick people. As casualties grew rapidly in Sweden while they attempted to follow a path between prohibition and these recommendations, the press shared photos of people sitting crammed in parks, restaurants, and coffee houses.

The strategy, which was followed on March 25, was criticized and considered to cause a lot of casualties. 2,000 academics gathered signatures against that strategy. On April 14, 22 academics who are well known to the general public strongly criticized the strategy which was monitored by the press, but Sweden, led by Tegnell, adhered to the strategy set by the Public Health Authority and the theory of “herd immunity”, even if they didn’t call it this explicitly.

Speaking about the growing criticism and questioning in foreign media, Swedish Foreign Minister Ann Linde said: “It is a fabrication that life continues as normal in Sweden. Industry has stopped, people lost their jobs and many companies went bankrupt. Sweden has not been closed fully but it has been closed in some areas and the impact on society is huge.”

Pixabay

While Ann Linde’s remarks were still in the headlines, a new scandal erupted on April 18. It turned out that Europe’s “jet society” had fled Europe in quarantine and came to Stockholm, which had a reputation of providing good hair and personal care, eating in restaurants and having fun at night during the coronavirus. The press wrote that rich women who paid €1,800 to fly there from Switzerland enjoyed “freedom” in Stockholm. EU countries, Britain, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland were excluded from Sweden’s list of countries on which they imposed flight bans.

After this news spread, the government announced that “the Swedish people are largely complying with the recommendations, but because of the observed necessity, municipalities will increase their control in restaurants and similar establishments”. Subsequently, inspections were carried out in restaurants and similar establishments, and restaurants which did not reduce the number of tables and did not take precautions to keep right distance between people were closed. Now let us see how taking this path has affected Sweden.

Healthcare improvements

Institutional erosion had taken place in Sweden’s healthcare industry since the 1990s followed up by the privatization policies of the conservative coalition governments that came to power in the 2000s. Once liberalization merged with the laxity of the collapse of the USSR, laws regarding regulations of preparation for crisis situations were repealed. The education and healthcare sector were hit hard by privatization. Instead of central decision bodies, regional bodies were authorized for the public health. It became unclear how medical supplies and drugs would be stored and by which body. Crisis warehouses which were prepared to meet the food and health needs of the people for months in the event of a crisis or war in various parts of Sweden were emptied. With the outbreak, a shortage of the most basic medical materials, such as masks, vizors, protective aprons, disinfection materials and anesthetic drugs began. The government then stepped in and appointed the General Directorate of Social and Health Affairs and decided to manage the storage and distribution of medical supplies and medicines centrally. It was also revealed that intensive care beds, the number of which had been reduced to 574, would be insufficient to meet the needs of the outbreak. As a first measure, hospitals have strengthened their intensive care capacity. Afterwards, in cooperation with the army and civilians, a part of Stockholm fair was turned into an intensive care hospital. Thus, intensive care beds were increased to 900 in Sweden.

The devastating impact of neoliberalization in the 2000s also hit the military. Reductions in the army left only two hospitals out of 35 fully equipped as field hospitals in the event of a crisis. The army was only able to set up one 20-bed field hospital in Stockholm and one 30-bed field hospital in Gothenburg.

The lack of intensive care beds in Sweden raised the question of who would be given “priority” for treatment. Videos spreading from Italy and Spain intensified the debate. When the directives published by Karolinska Hospital leaked to the press, things quickly became chaotic. Those over 60 with the history of chronic diseases in one or more organs would not be given intensive care. Doctors said people with no history of disease and chronic ailments were more likely to respond positively to treatment in intensive care. That response did not really have a calming effect on the public. Meanwhile, a case reviewed by Swedish Television dropped like a bomb. An 80-year-old covid-19 patient, a Swede of Assyrian origin with no underlying illness, was not taken to a hospital in Södertälje, a Stockholm suburb, where he died. On the other hand, a 99-year-old ethnic Swede who had been diagnosed covid-19, was sent home in the Stockholm suburb of Nacka and was released after three weeks in intensive care. At the same time, newspaper reports raised doubts about “ethnic discrimination” in the fight against the epidemic. Recently, a new health scandal occurred. A patient of Turkish origin who was in intensive care died as a result of the closure of the respiratory device without the consent of his family.

On May 8, the media reported that Karolinska Hospital, Sweden’s most renowned medical institution, forced paramedics who tested positive for covid-19 to continue to work. According to the epidemic protection guidelines, medical personnel who do not show any signs of disease must stay at home for 48 hours if the test result is positive. It turned out that the hospital had agreed with the Stockholm Department of Epidemic Protection to avoid compliance with this rule. From the beginning of the outbreak, the aim was allegedly “protecting the elderly” and accordingly, elderly care homes were closed to visitors after the first cases. Nevertheless, the outbreak reached the elderly and quickly took many lives. In the absence of medical supplies, a new circular for protective usage has been issued for staff working with the elderly, permitting staff to work without masks, visors, and aprons. When the unions objected to the illegal practice threatening to cease work, the matter was moved to the business courts, where the employer’s decision was justified. When it became clear that unprotected care personnel were carrying the disease from room to room, new arrangements were introduced, but it was too late. One-third of all deaths in Sweden are elderly people living in retirement homes. In Stockholm, half of the deceased were elderly people in these homes. In other words, since the early days of the outbreak, the elderly who were supposed to be “protected” had largely perished. Anders Tegnell, the architect of the Swedish strategy, and Social Affairs Minister Lena Hallgren, had to accept that the risk of contamination in care homes for elderly was a big problem and that they had failed. The health sector’s protective material gap was still not met, but at least the panic of the early days seems to have calmed a bit. The Swedish Public Health Authority currently does require people to wear a mask in public. On the contrary, “those who are sick can use masks, but if they stay at home until they recover, they don’t need to,” it declared, taking a different stance than all current research has suggested. On the other hand, almost no masks are currently available for purchase in the country in any event.

There are no common tests offered in Sweden. The number of tests is supposed to be increased in May, but no tests have yet been carried out except for some strategically important professional groups (health, fire, police, logistics services). Private health organizations can carry out tests for about 2,000 Swedish crowns. The results of a joint survey of herd immunity from Stockholm University and the University of Nottingham, England, were announced on May 9. Math professor Tom Britton calculated that herd immunity could be reached in Stockholm at a rate of 40-50%. According to the model, the average person infects 2.5 people with the disease. In this case, herd immunity is expected in Stockholm in mid-June. However, the latest findings from Spain contradict that claim. Anders Tegnell warned the public to maintain social distance and continue to wash hands, saying that even if the herd immunity is reached the danger will not have passed.

ECONOMY AND EUROPEAN UNION

As the outbreak began, large corporations stopped production, and many workers lost their jobs. Unemployment reached its highest level in Swedish history since the 1930s. The projected unemployment rate for 2020 is 11%, which may reach 14% in autumn. As the government prepared a crisis package to save companies, it also took measures for people who were unemployed through the governmental Employment Agency. A support budget has been allocated for summer work, temporary jobs, job training and similar measures. Various support packages have been created also for small and medium-sized companies, such as temporary reduction of employer payments and rentals, and in the event of illness, the share which is paid by employers to the workers has been taken over by the state. However, in the migrant-intensive service sector there is no state support.

Additionally, people who have been out of the job market for a long time have been given extra funding to work in the nature and forest industry, so called “green jobs.” Low-wage workers from the Far East and The Baltic countries are not allowed to take this employment this year. Priority seems to be given to immigrants already in the country. The criticism of the unions was swift when large-scale companies tried to take advantage of the governments’ package of measures to recruit “new” workers instead of their own, who they put on temporary leave. Meanwhile, the big companies that received economic aid from the state distributed the dividends to shareholders, leaving the government in a difficult situation. The government has set up a “corruption” investigation commission with the support of opposition, declaring that it will not accept the irresponsibility of companies which receive public funds.

Questioning the “spirit of solidarity”

When the outbreak began, the borders were closed, and logistics services stopped. EU Member states turned their backs on Italy, which was calling for health care workers and supplies. Member states did not export their own medical supplies to other EU member states, in fact, they stole medical supplies that did not belong to them that were in transit to other “sister countries” in the Union. France issued a “law to confiscate any material that comes to its ports in extraordinary circumstances” which may be needed to deal with the epidemic. In short, the EU’s alleged “spirit of solidarity” was shown to be a lie.

Prime Minister Stefan Löfven issued a statement on May 9, which is ironically ‘Europe Day’, saying the EU’s solidarity was inadequate. He spoke about the importance of the EU’s core values being valid during the crisis and politely criticized what had happened thus far. Stressing that the best medicine against all crises is cooperation in the EU, Löfven also said that the EU, which supposedly respects democratic rights and freedoms, is important for peace in the world and should strengthen its role. In Sweden, many factories moved their production abroad under EU compliance and competition laws. Sweden, which depends on exports and imports, is far from Europe. Therefore, when the borders were closed and logistics services stopped, there was a fear that food supplies could be a problem. However, the Ministry of Commerce and Agriculture announced regular cooperation with the biggest actors in the food market and announced that they had taken measures to prevent problems in imports of fresh vegetables and fruits.

Immigrants and refugees

As soon as the outbreak began, migrants started to die in densely populated areas. The Government and Public Health Authority built a strategy on the individual responsibility of citizens and that strategy was based on the assumption that everyone would comply with the recommendations.

Since leaflets about the outbreak were not published in all immigrants’ languages and since not everyone is literate, the migrant groups did not have access to the necessary information about the outbreak. It was not possible to obtain information through computers and mobile phones due to the lack of information in different languages and technological infrastructure. Some migrants who did not care about danger and did not take “individual responsibility” were the first victims of the outbreak. Poverty, large families living in cramped small houses, families continuing their habit of visiting each other, all contributed to the increase of the risk of epidemics in these areas.

For years, there has been a trend imprisoning immigrant women into the “caregiver” sector. In addition to the many young girls who were directed to health vocational high schools by consultants during their education, unemployed, unskilled inexperienced and uneducated women are also directed to customized health care institutions and homes for elderly care with low hourly wages. In addition, most migrants live in densely populated areas. It is now claimed that the spread of the outbreak has been mainly caused by people working in the above-mentioned workplaces, shuttled between large families, school children and businesses. Research has shown that people living in migrant-intensive areas have multiple health problems. In these areas, people work mostly in the service sector in low-paid jobs and have no possibilities to work from home. They must go to work by trains and buses. Many migrants, including 22 Turkish citizens, have died because Swedish politicians and institutions do not know the structure of these regions, have not listened to the problems that have been repeated for years, and do not prevent discrimination. The issue of epidemics and migrants is an indication of failing Swedish integration policy.

Some asylum seekers who were put under surveillance to be deported were sent to various countries, filling the planes before the borders were closed. On the other hand, with the spread of the outbreak, those under surveillance were released unsupervised. Now it is not known where these people live and there is a duel between the institutions about “who has the authority” of having information of their whereabouts and having responsibility for their financial maintenance. Meanwhile, the government is preparing a law that quietly regulates asylum applications with the support of opposition. According to that proposition, those who have been denied asylum or residence will be able to apply for asylum in Sweden again first after 10 years, not after 4 years as it is now. The Swedish experiment is ongoing. We will see the final results soon enough.

Day by day measures

31 January 2020: The first case was seen in Sweden (recent research points to November)

March 6: It was confirmed that the outbreak had spread.

March 11: The first death occurred in Stockholm.

March 16: The first crisis support package for companies was announced.

March 17: travels are restricted

March 18, high school, adult schools and universities were closed, distance education replaced the traditional education. More than 500 people have been banned from gathering.

March 19: Travels were restricted to only in cases of necessity.

March 25: The second crisis package for companies was announced.

March 27: More than 50 people were banned from gathering.

March 30: All visits to the elderly’s home were banned to protect the elderly from the outbreak.

April 7: Radio Sweden reported that the outbreak was spreading rapidly in migrant-intensive areas, the number of cases across Sweden has tripled.

May 14: the press press reported that only 5% of the population in Spain had contracted Coronavirus despite huge numbers of deceased in the country to the date. That fact is considered to be contradictory to the possibility of herd immunity.

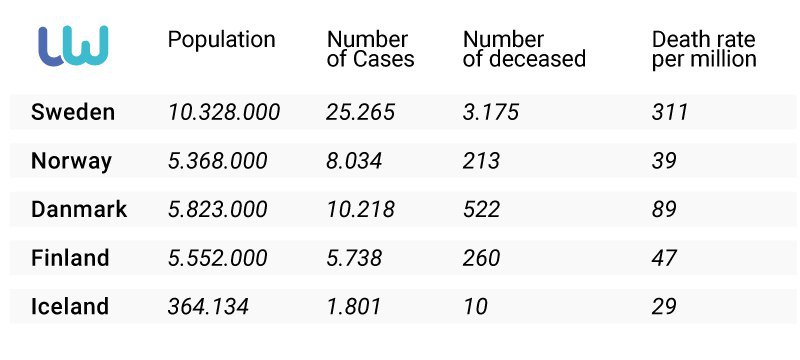

Comparison of Sweden and neighboring northern countries that have shut down their own systems (statistics as of May 8):

Leave a Reply