By Sergio Rodriguez Gelfenstein

The leading world powers convened between November 1884 and February 1885 in the city of Berlin, invited by France and Great Britain and organized by the Chancellor of Germany, Otto von Bismarck, to organize the division of Africa. A few years later, in May 1916, through the Sykes-Picot Agreement, Great Britain and France did the same in Western Asia and North Africa.

These colonial divisions came to consecrate the world power of Great Britain, but in this instance, it had to be a shared power, first with France and later with the United States. However, there was a period in history when Britain was mistress of the planet, beginning with the astonishing increase in productivity as a result of the industrial revolution. As a substantial part of its power, Great Britain built and developed a gigantic colonial empire.

One hundred and fifty years later, the colonial footprint is still present throughout the planet, in some regions still through its original expression, and in others, in the form of neocolonial control to maintain the threads that allow the domination of a good part of the planet. It is worth looking at the rectilinear layouts on the maps derived from the emergence of national states in the spaces drawn by the metropolises after the division of the planet. For this, the opinion and acceptance of the native peoples of those regions who lived in such territories since ancient times was not counted on.

Likewise, it is necessary to observe the enormous number of latent conflicts emanating from the metropolises after withdrawing from their colonies, defeated or forced by circumstances beyond their control. For example, the territory of Kashmir that should have been Pakistani, remained in India. Kuwait, an Iraqi province, was elevated to the status of a national state by London. Jordan, was invented by no one knows whom, to be given to the Hashemite dynasty as a consolation prize for having been displaced from Arabia, which was, in turn, given as a reward to the Saud family, for their dogged loyalty to Great Britain.

In Africa, Tutsis, Hutus, Bantu, Tuareg, Maasai, Mursis, Zulu and hundreds of indigenous peoples saw lines of separation drawn from their ancestral territories, being forced by force to speak foreign languages and accept strange religions. From one day to the next, they saw to their horror that in their communities, one part had to speak French and the other English, in addition to having to “ask for a visa” to visit their relatives who lived in nearby communities.

Already at the beginning of the 19th century, Great Britain knew how to combine its naval dominance, enormous credit capacity in finance, great commercial experience and successful alliance diplomacy to become the global hegemonic power. Thus, the industrial revolution came to strengthen a position that had already shown great success in the mercantilist and pre-industrial struggles of the previous century. In 1815, the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte consolidated English hegemony.

Latin America and the Caribbean were not immune to these circumstances. The conflicts in Europe and the unpredictable victories of one side or another concluded with agreements that transferred possession of a colonial territory from one sovereignty to another. Thus, for example, Trinidad and Tobago were ceded by Spain to Great Britain by the Treaty of Amiens of 1802. Aruba, for its part, which was occupied by the Dutch in 1636, remained under their control for almost two centuries, becoming the domain of Great Britain in 1805 and returned to Dutch control in 1816. Another case is that of Belize, a territory that Great Britain occupied in 1638, kept it in constant tension with its Spanish neighbors until in 1798, Madrid was definitively displaced, making it the only British colony of Central America with the name of British Honduras.

In this period at the beginning of the 19th century, taking advantage of its unlimited power, from its small possession in Guyana, Great Britain began its westward expansion in 1814. Thus, the original 20 thousand miles² of its colony were expanded to 60 thousand in the middle of the 19th century, to 76 thousand in 1855 until reaching 109 thousand miles, equivalent to 159 thousand km².

In this international context, President Monroe’s declaration of December 2, 1823, which became a foreign policy doctrine of the United States, took place. At the end of the century, already in the midst of the imperialist stage, Washington began to give greater continuity to the application of this doctrine: in 1898 the United States intervened militarily in Cuba and in 1903 promoted the secession of Panama from Colombia to seize a territory that would allow it to build the much-desired canal. At the beginning of the 20th century, Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft implemented new modalities of intervention that were known as “Big Stick Policy” and “Dollar Diplomacy.” Within this framework, the United States occupied Cuba between 1906 and 1909.

Likewise, in the Venezuelan crisis, which began in 1902 when warships from England, Germany and Italy bombed and blocked Venezuelan ports to demand payment of debts acquired during the struggle for independence, the country’s government invoked the Monroe Doctrine before which Washington acted to “appease” the Europeans in exchange for which it promised to force Venezuela to meet its financial commitments.

All of this contrasted with the Bolivarian tradition of unrestricted defense of sovereignty. With his infinite wisdom, the Liberator Simón Bolívar, already in 1819 during his speech at the Congress of Angostura, established clear principles and doctrines for the creation of the American republics that would be established. In the case of Colombia (to which Venezuela belonged), in 1821 at the Congress of Cúcuta, the plenipotentiaries welcomed the idea of the Liberator and established a precise delimitation of the national territory. By doing so, a Doctrine of International Law had emerged emanating from the uti possidetis juris of 1810 that accepted as legitimate title the possession in which the American territories had been and to which they were entitled by virtue of the provisions that had generated their creation.

We owe Bolívar this initiative that was incorporated into the legal system of the nascent republic. The Liberator foresaw with extraordinary long-term vision that the boundary discussions between the new republics would generate serious inconveniences, so it was necessary to draw up defined rules that would give legal bases to all and avoid problems of international public order. Nobody knows how many wars the Liberator avoided for Our America. As history has shown – unlike other regions of the world – our border problems have been negligible when compared to other continents.

In this context, Venezuela permanently protested the arrogant and expansionist attitude of Great Britain. For this reason, in 1896 the United States and Great Britain began talks on the latter’s border problem with Venezuela. This led in 1897 to a treaty to establish arbitration.

The United States managed to impose arbitration conditions that were absolutely harmful to Venezuela and favorable to Great Britain. This arbitration is the one that in 1899, outside international law, failing to comply with the rules that had been established and without Venezuela being able to present its arguments, failed to legitimize the usurpation through an award. The true extent of the plundering only became known many years later.

In 1949, a memorandum written by the American lawyer Severo Mallet-Prevost was released, who had acted as Venezuela’s advisor in the negotiation. In the document, published after his death, Mallet-Prevost recognized that the award was the product of a political arrangement between the United States and Great Britain that led to an arbitrary drawing of the border, agreed upon outside international law. It is worth saying that two of the five judges who ruled were British and two others were Americans.

This demonstrates the flawed nature of the award and is the reason why no Venezuelan government has recognized it. In 1966, Great Britain finally agreed to begin negotiations with Venezuela, reaching the Geneva Agreement of February 17, 1966. This document was recognized by Guyana when it acceded to its independence on May 26 of that year.

Venezuela, in turn, recognized the independence of Guyana, reserving the maintenance of its historical claim and therefore recognizing the sovereignty of the new State from the territory east of the median line of the Essequibo River from its source to its mouth in the Atlantic Ocean. Since then, the dispute has remained friendly.

However, recently there was a first alarm signal showing an alteration in this situation, when Guyana refused to continue the work of the good officer designated by the United Nations. This was an unequivocal indication that announced Guyanese intention to take the conflict through another route. Unfortunately, that was the case. Guyana decided to give a concession to the American company ExxonMobil, which, under imperial influence and supported by its government and by powerful transnational economic and political interests, proposed to escalate the conflict to put Venezuela in the dock as a beachhead for a new interventionist escalation against Venezuela that has taken the dispute – illegally – to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which has no jurisdiction over this matter.

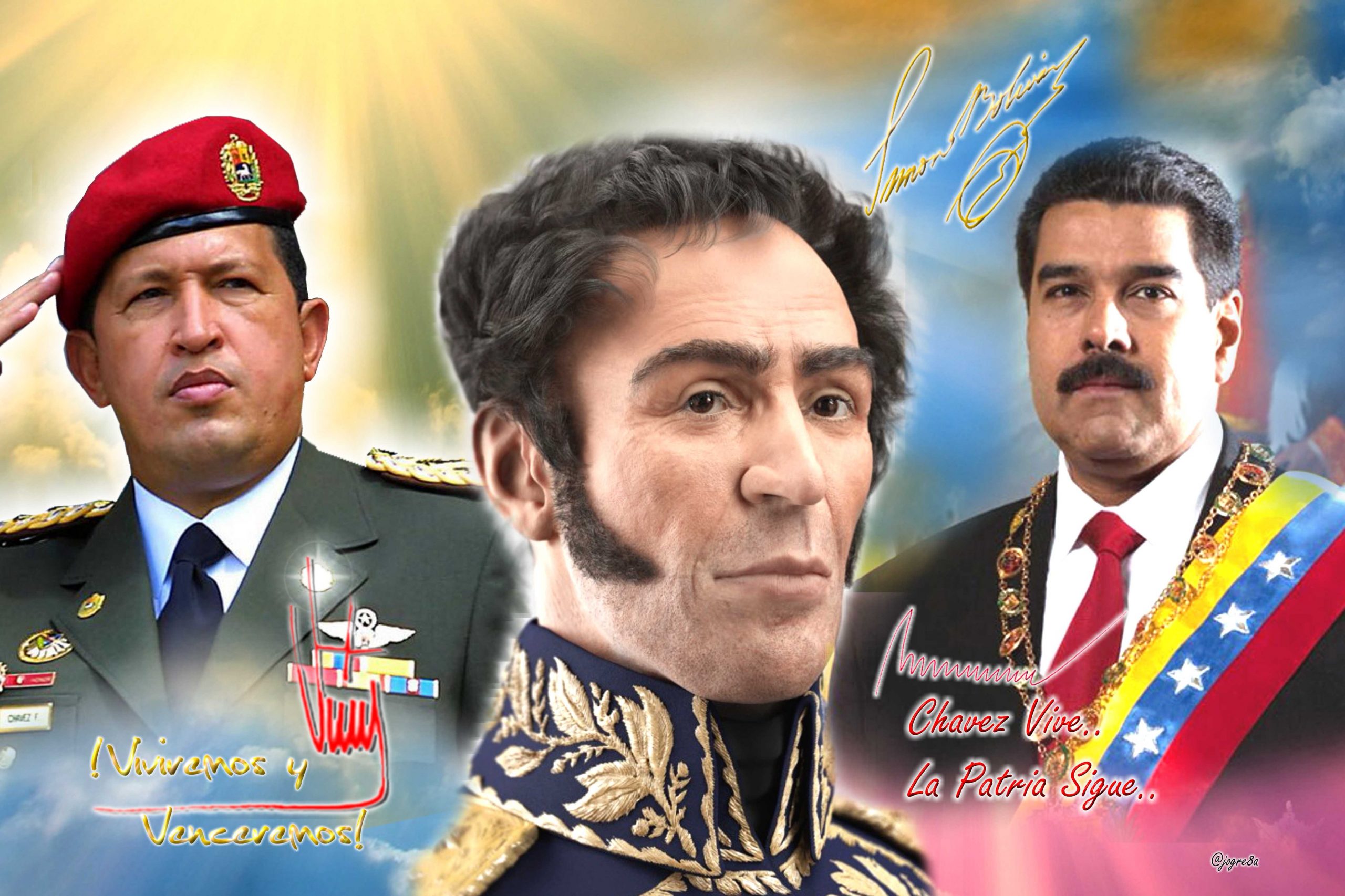

Hugo Chávez’s original eclectic thinking and his accelerated political and ideological evolution led him from upholding nationalist, patriotic and Bolivarian precepts to clear anti-imperialist and even socialist ideas. Accordingly, his reflection and practice also progressed in terms of his view on the Monroe Doctrine and its effects in Venezuela and Latin America and the Caribbean.

His deep Bolivarian sentiment, supported by a deep knowledge of the life and work of the Liberator, led him to almost naturally support his rejection of Pan-Americanism and the interventionist derivations that emanate from the Monroe Doctrine.

In the great battle fought in Mar del Plata against the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA) presented by the United States in November 2005, Chávez began to outline the idea of continuity outlined by the Monroe Doctrine, Pan-Americanism and this new proposal of the United States. In his speech during the popular rally in support of Latin American and Caribbean politics and against imperialism in front of the Miraflores Palace on November 19 of that year, he outlined precisely the form that anti-imperialist thought and practice should take.

When referring to his participation in the event in the Argentine city, he expressed: “There we Venezuelans arrive, determined to continue resisting imperialist aggression, to continue saying ‘no’ to the imperialist proposal to engulf us, in a proposal – as I have already said – very old, but it changes its name as the years, decades and centuries go by. They already called it the Monroe Doctrine at one time, more recently the Initiative for the Americas and then, the FTAA proposal, FTAA, FTAA, Fuck it! FTAA! Fuck it! It’s leaving, we’re sending the FTAA to hell! Very far away, because here we will have a homeland, here we will be free, we will not be a North American colony, we prefer to die a thousand times, before Venezuela becoming a North American colony again.”

In the future, Chávez’s Bolivarian integrationist thought was filled with an anti-imperialist support that permeated his work in the construction of instances of Latin American and Caribbean union far from the Pan-American imprint. In 2011, when defining the purposes of the nascent Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), he expressed that it should be “a protective shield against interference […] even a firewall against imperial madness.” Likewise, he conceptualized the new organization as “the most important political, economic, cultural and social union project in our contemporary history,” forever banishing any hint of acceptance of the Monroe Doctrine and its influence as support for the integrationist project of the region.

The previous lines allow us to appreciate that from Bolívar to Chávez, the mark of the Monroe Doctrine has always been present in Venezuela. Over time, its trail has marked the future of Venezuela’s life as an independent nation.

Latin America and the Caribbean have revolved around the diatribe between Bolivarism and Monroism. Our condition of being the native country of the Liberator, in which he developed the first years of his political life, leading Venezuela to its emergence as an independent and sovereign nation, indicates the course of a footprint that in political and economic terms, but also in the planes of culture, identity and symbols have established the course of the country. Even in those moments in history when governments have been closer to Washington than to their own national interests, the condition of nest of Bolivarian ideas has been presented to give continuity to the spirit and feeling of nation.

It is true that after Bolívar came Páez and the subordination of the country to the oligarchy. It is also true that after Cipriano Castro, Juan Vicente Gómez arrived to deliver Venezuela and its oil to the United States. But the arrival to power of Hugo Chávez and his extraordinary pedagogical work in terms of making history known with a refoundational criterion, appealing to the revision of traditional arguments, which were shown as pristine truths of our past and that in this way he was taught to the new generations as part of the annals that gave rise and continuity to the Venezuelan nationality, have come to produce a schism in the interpretation of the past life of the country.

The publication in 2000 of version number 4 of the Santa Fe documents, prepared by a commission of ultra-conservative American experts just a few months after Hugo Chávez came to power, clearly aimed to contain his integrationist impulse under the accusation that “relying on Bolivarism, [Chávez] aspires to form Gran Colombia (Venezuela, Colombia, Panama and Ecuador), probably as a socialist republic.”

After that, came the coup d’état of 2002 and the oil strike and sabotage of the same year, which marked the prelude to a rosary of continued attacks until on March 8, 2015, President Barack Obama signed an executive order by which declared Venezuela “an unusual and extraordinary threat” to the national security of the United States.

In this way, a legal reason was established to begin a permanent process of aggression against Venezuela that continues today. This decree has continued to be renewed annually during the administrations of Donald Trump and Joe Biden. The ghost of the Monroe Doctrine and Pan-Americanism continue to appear in the spectrum of Bolívar’s homeland. Two hundred years later, the enemy is the same.

Leave a Reply