The coronavirus pandemic has more-or-less monopolized cultural imagination in the West, sparking deep reevaluations of our founding myths and values. Even celebrity worship, one of the West’s most cherished institutions, has become a site of bitter resentment, from the public’s passionate disinterest in tone-deaf movie stars pandemic-inspired rendition of John Lennon’s “Imagine” to their rage over the preference the rich and famous have been given in terms of testing and treatment. This change in mentality was likely only possible at the brink of apocalypse, given that most of the world had come to accept the ideology of global finance as a kind of fact of nature, with populations submitting to austerity, cultural degradation and poverty with a humble devotion a saint might envy. It is an unfortunate fact of history that social change only becomes possible when the other option is death… and sometimes not even then.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, blockbuster films about world-annihilating natural disasters became something of a cultural staple, particularly in the United States. Until that moment, the Deus-Ex Machina that threatened American lives and way of life was a real place, however buried beneath Cold War ideological projections. The “threat” facing the West was also more-or-less human: the worst outcome we could imagine were our own most powerful tools, atomic bombs and nuclear accidents. When liberalism reigned triumphant in the 90s that specificity was lost. A unipolar system with Washington at the helm now controlled or regulated every corner of the globe, and for the first time in history, there was nowhere to flee, even theoretically. Apocalypse made for appealing cinema because it threatened to expose the limits of political power structures which seemed hegemonic, reminding us that there are always elements that cannot be controlled, that there is always an ‘outside.’ Movie-goers watched the films together in large public theaters, their faces mirroring the startled awe of the crowds in the film who stood together in anticipation of their collective end. At the very moment it seemed we were all finally free to “be ourselves”, we were hopelessly dreaming of experiencing collectivity… even if it could only be our collective end.

Pandemics, on the other hand, are very different types of disaster scenarios, operating around a cruel ironic twist worthy of the science fiction genre, in that the cause of our demise is the very thing we need to survive it: one another. While we experience the coronavirus collectively, we are forced to respond to it in quarantine and isolation, relegated to the safety of our commodity stuffed apartments, while all interactions are relocated into the digital ghetto of social media where they can be carefully curated by the megacorporations that have monopolized our experience of the internet, and now, eachother. The classic philosophical problem of the relationship between the individual and society has taken on incredible new dimensions throughout the early stages of the epidemic, but will the potentially ideological implications of “social distancing” carry over once the danger has passed, preventing us from being able to even imagine an alternative? Are we closer together, or further apart?

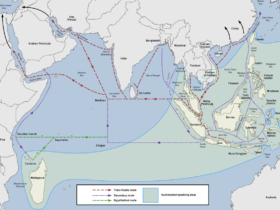

To answer that question, it is important to understand that liberalism itself emerged in response to a context of crisis. Classical liberalism developed in tandem with the turbulent rise of industrial society and maritime capitalism, providing an intellectual basis for the new political structures that came with the death of kings and the end of empires. Naturally, the ideology has shifted over time and adapted to fit the conditions of the contemporary era. Neoliberalism emerged in the 1970s in response to economic fallout and the growth of the workers’ movement in the West– that being said, it has always really been less of an ideology and more of an intellectual strategy for fostering the dictatorship of the market and ruling class. Neoliberalism shed the extraneous religious elements and social responsibility one finds in Adam Smith or John Stuart Mill, while upholding the principles of small government and “individual freedom” in their most radical forms. This, however, is not because liberal governments actually believe in the liberal principle of the fundamental value of the human individual adapted from the enlightenment– individualism is important for the neoliberal project because it is politically useful in convincing people that politics is something a person chooses when they cast a vote or selectively spend their money. This helps maintain the notion that something like poverty is a personal failure rather than a result of structural violence, making effective resistance unlikely or impossible.

PxFuel

In the context of the coronavirus, the foremost neoliberal governments such as the US, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands are among the states to take this rationale to a logical extreme, at least initially suggesting a laissez-faire approach even in the face of a deadly pandemic, i.e. allowing the disease to spread and kill off the weak in order to culture “herd immunity” among the population. In some of these cases more than others, it has become opaque whether or not the country’s leadership understands they are killing people off in order to keep profits coming, or if this way of thinking has simply become so naturalized they actually see it as the only good course of action. Others, like Donald Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, have explicitly stated preference for profit over human lives.

Regardless of the motivations, such measures have quickly proved untenable, particularly as people and governments began comparing the bodies piling up around them to the remarkable statistics emerging from China, where collectivism, centralized planning and people-first politics have all but halted the spread of the virus. While Trump has desperately tried to get the public to blame China for the virus, his effort to rename the virus in its honor has not proven quite as successful as Beijing’s remarkable global campaign. Not only have the supposedly “totalitarian” governments of China, Vietnam and Cuba managed to contain the epidemic domestically, they have been at the forefront of providing aid to countries around the world, including hard-hit places like Italy, which the EU, that alleged bastion of human rights, has abandoned to mass-death. Should we be surprised to see Serbia ceremoniously swapping the EU flag for that of the People’s Republic of China?

This, however, puts liberal ideologues in a rather odd position. For centuries, it seemed virtually uncontested that Europe and “the West” were the pioneers of human freedom, that their approach which privileges the sovereignty of the individual and democracy is what separated them from those governments they called “authoritarian”, of which China was supposed to be the most heinous example. Now, China, for all its alleged “totalitarianism” and failure to protect the rights of the individual, is the same government clearly ready to sacrifice its economic success to protect lives– for their own sake. As it turns out, the fundamental connection that supposedly exists between individual rights, economic pragmatism and concern for human life is not so fundamental afterall. In fact, liberal democratic emphasis on the individual has turned out to be in contradiction with an emphasis on the value of life when it comes to handling the coronavirus. The relationship between the individual and society has proven far more complex than it seems at the surface: the Chinese have retreated to their rooms, but as a society, meanwhile, most of the West will continue to come together in public, leaving every man for himself.

In conclusion, it is clear that the EU has not only been unwilling to help the rest of the world (including their own member states), they have been unable: the ideological values and structures of state they have long asserted to be “progressive” and a natural consequence of historical change have been revealed to be backward, even barbaric. While our potential solutions seemed far more bleak at the dawn of the era of unipolarism, history teaches us that crises have a tendency to hasten broad political change. The coronavirus itself was only the catalyst which accelerated and revealed the inner contradictions of broader social systems and ideologies. Despite what its politicians and philosophers have stressed during its centuries of domination, the West has no monopoly over terms like “democracy”, “freedom” or “humanism”– in fact, they never have. It is all too fitting that China, a country terrorized by this supposed “humanism” for centuries, has finally exposed its former colonizer, providing the rest of the world with a true alternative rooted in collectivism and socialism. Even Western leaders themselves (Macron, Merkel) have begun to realize this, adapting more socially focused and far reaching measures… but these actions will likely prove too little too late. The solution requires a radically different model on both a national and international scale, something we are now seeing emerge from the wreckage of liberalism.

Leave a Reply