Over the last two decades, decolonisation has been the subject of much debate in the educational sphere. The Rhodes Must Fall movement further catalysed this process in a substantial way. Decolonisation is defined as the undoing of the narrative and the mindset of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby a nation establishes and maintains its domination of foreign territories, such as the Dutch and the English did in South Africa from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

Western Eurocentric historical accounts and their political discourse of power constitute a political construct that attempts to negate indigenous peoples and their experiences around the world, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Gulf of Mexico. The truth is that European colonial history has left a bitter legacy behind on the African continent.

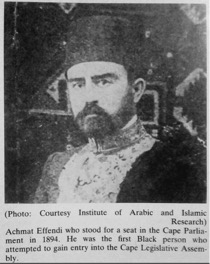

In South Africa, many Muslim thinkers such as Dr Abdullah Abdurrahman, Tuan Guru, and Ahmet Ataullah Effendi (denied a seat in parliament in 1893 by Cecil John Rhodes) also faced this cruel, racially, and culturally dehumanising system which regarded them as second-class of citizens. This article focuses on the contributions of Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi, a forgotten freedom fighter in South Africa’s colonial history.

The University of Cape Town is thinking of renaming some buildings on campus in order to decolonise the university. This is indeed a remarkable movement to teach the new generation what has been forgotten and left out from the history books. One of these forgotten figures was Sarah Baartman, a victimised Khoikhoi woman whose dignity was reclaimed in part by renaming Jameson Memorial Hall after her.

Turkish input to African identity

Another interesting forgotten character was Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi, who was born in Cape Town in 1865 from a Malay mother and a Turkish father. Ahmed Ataoullah studied in Cape Town, Mecca, and Istanbul, became a professor of Islamic theology, and returned to South Africa in 1880. Due to his father’s relations with the Ottoman government, he established an Islamic school in Kimberley to teach Muslim pupils. While Ahmed Ataoullah was promoting educational activities in South Africa, he decided to stand at the Cape parliament for the rights of victimised people in South Africa. Due to his religious identity, he was also treated as though he were black despite his white skin colour. As a result, historian Ahmed Davids noted that “Achmad Ataoullah Effendi was the first black politician in South Africa”.

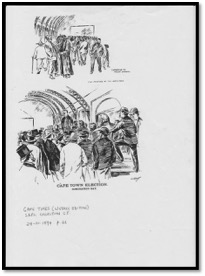

Other than academic sources, discoveries in the dusty pages of old newspapers, preserved in microfilms, tell us about unsung heroes in South Africa but also give us the opportunity to understand the challenges of black people in the colonial past. The political struggles of the first black politician of South Africa, Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi, also inspired Xhosa people in South Africa in their struggle. In the Imvo Zabantsundu (Native Opinion), a news article published in February 1893, shared interesting news in its columns regarding the political challenges of Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi. According to the news, Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi was the first politician to fight for Black South African people.

A forgotten freedom fighter Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi according to isiXhosa newspaper of South Africa, Imvo Zabantsundu 1893

Forgotten freedom fighter Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi

Another newspaper from the same period confirms the political protest of Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi against Cecil John Rhodes’s policy at the Cape. At the time, Effendi stated: “It is the first time in the history of South Africa that a non-European has stood for Cape parliament. I have the moral courage to do so” (Cape Argus, 30 Jan 1894). Strangely enough, his brother, Hesham Neamatollah Effendi, also fought against racial discrimination in 1903 stating,

“As a Muslim community we are all part of another, although there are many European Muslims here, but for the sake of being Muslim, they are classified as Coloured or Asiatic. Now what are we going to do? Are we going to sit still and allow them to march the station with our wives and children sheep as was done to the natives? No, certainly not! We shall have to protest against such legislation.”

This documentation shows us that the Effendi family members were some of the prominent freedom fighters in South Africa. Another newspaper, The Rhodesia Herald, on Aug, 29 1913, informed its readers about the first “non-white” pilot of South Africa, who was, in fact, the son of Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi.

Building a national identity in South Africa was not as easy as one might have thought. One of the reasons for this is that the historical background of the former colonies does not always allow one to talk openly about unresolved matters such as national identities in multiracial contexts like South Africa. Coloured identity must be one or the most complicated identities to define, which Prof. Adhikari theorized in his book entitled Not white enough not black enough, which examines the destiny of people of colour in South Africa.

In the nineteenth century, South African national identity was not only based on ethnic belonging but on religious identity as well. In spite of his religious affiliation, Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi’s political protest was regarded as an important step towards decolonisation in South Africa. Because of his fascinating life story, Ahmed Ataoullah Effendi deserves to be remembered as a man who shared a common destiny with many South African people of colour, and as a national hero in the country.

Conclusion

Though geographically distant, the Ottoman state was present even in the farthest corners of South Africa through its various activities. The economic relations initiated in 1838 were replaced by educational activities over time. The relationship between the two territories began with Professor Sayyid Abu Bakr Effendi’s assignment to South Africa to provide religious education for Muslims at the Cape of Good Hope in 1862. Abu Bakr Effendi’s students and their children formed the new generation of intellectuals in the region. After Abu Bakr Effendi’s death in 1880, Mahmut Fakih Effendi’s educational services in the region strengthened the Ottoman cultural presence in South Africa.

With the death of Abu Bakr Effendi, his endeavours in education were taken over by his sons, Ahmet Ataullah and Hesham Nimetullah Effendi. The Ottoman Imperial School which was established by Ahmet Ataullah Effendi in Kimberley played crucial role among young Muslim generation in terms of structuring the educational background in the territory. His brother, Hesham Nimetullah Effendi, opened an Islamic School of Theology in Port Elizabeth. Hesham Nimetullah also raised donations for the Hejaz Railway project and had an influence on the political scene thanks to the several meetings against racist policies in South Africa, including some held with the legendary Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi in Natal and Durban.

With its historical buildings such as the Nur al-Burhan al-Islam and the still-fashionable Ottoman fez, the Ottoman state has had a strong influence on the South African community. This is most clearly and forcefully demonstrated in their joint ancestry and historical solidarity.

Leave a Reply