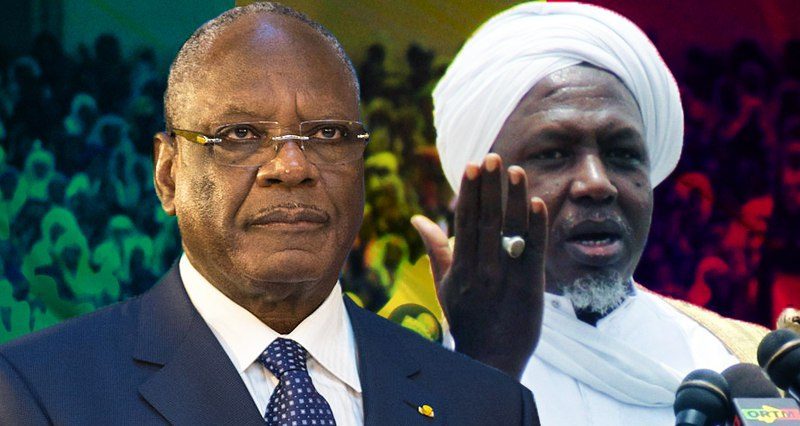

In recent days, Mali has been engulfed by a series of dangerous interconnected events – a violent confrontation with an al-Qaeda cell, ethnic conflicts, as well as protests demanding the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, fuelled by rising anti-French sentiment.

Sahel chaos: How terrorists are taking power in Mali, Niger and the region as a whole

Keïta is taking a risk

In Mali, civil protests continue unabated – from simple demonstrations with posters and slogans to shootings outside the presidential palace.

La Destitution de IBK au Mali en marche vers le Sénégal bientôt ! Ready pic.twitter.com/ICsCbxmJQq

— 𝐂𝐈𝐓𝐈𝐙𝐄𝐍🇸🇳 (@Citizen_PR) June 5, 2020

Malians are demanding the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta – there were signs among the crowd which read “IBK, get out” and demands for the release of the kidnapped former prime minister, opposition activist Soumaïla Cissé (who disappeared March 25 on the eve of parliamentary elections).

🔴Urgent Bamako Sous Haute Tension Ce Vendredi 5 Juin.

Les Maliens Ne Veulent Plus De IBK #Mali pic.twitter.com/TR0G32Xael— Tava Kebe (@KebeTava) June 5, 2020

Keïta is not popular among the people, and for good reason. First of all, he is openly associated with the French neocolonizers.

He is in constant contact with the French authorities, in particular President Emmanuel Macron, and justifies French presence in Africa.

In response to anti-French statements, Keïta told angry Malians not to bite the hand that feeds, including France’s. Even when he addresses the nation, he begins with a curtsy of Paris – for example, by expressing condolences to France over the destruction of Notre Dame rather than prioritizing his own people. It was under his watch when Operation Barkhan was launched which entailed the presence of foreign military troops.

Secondly, Keïta is blamed for the ongoing economic failure of the country. While the military is engaged in “Barkhan”, France is stealing local resources: at least 16 French companies are present in Mali, including subsidiaries of BNP Paribas, Total and Laborex. Mali receives about 3.3% of French exports to the Africa and Indian Ocean region. France is the country’s second largest supplier, ahead of Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire. One of the largest mining companies in Mali and neighboring Niger, AREVA, has a monopoly on resource extraction.

According to forecasts of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Mali’s economic growth rate is expected to drop sharply as a result of the coronavirus outbreak – from 5.1% of GDP in 2019 to 1.5% in 2020. The budget deficit is also expected to increase from 1.7% of GDP in 2019 to 5.8% this year. Such figures demonstrate the full dependence of the African country on the globalist system – and Keïta has only more integrated Mali into such structures.

Thirdly, during Keïta’s rule (which began in 2013) the problem of jihadists in the Sahel and ethnic conflicts has not been solved. On the contrary, Islamist groups have gained influence in neighbouring states as well, despite the presence of the French, and massacres in villages have become the norm.

The leader of the opposition – Dicko

Against the backdrop of ideological and economic collapse, it is not surprising that other leaders are becoming popular. In recent years, one prosthetic leader has been Imam Mahmoud Dicko: an authoritative intellectual among the people (more than 90% of Malians are Muslims), who received education in Saudi Arabia and is close to the Salafis. Some opponents even call him a “Wahhabi”, but he himself does not accept the label. The lines between the Imam’s political and religious activism are blurred, and many call Dicko the “Malian Ayatollah”.

Previously, he chaired the High Islamic Council of Mali (HCIM), a very important structure responsible for acting as a link between religious associations, mosques and political authorities.

Back in 2013, Dicko supported Keïta ‘s candidacy for president and was generally not against the introduction of the French army. But gradually, his attitude towards the president and the pro-French course began to change dramatically. In particular, he expressed the view that terrorists had been sent to Mali as punishment for modernist attempts to justify homosexuality, “imported from the West and flourishing in our society”.

Much of Dicko’s criticism of the president concerned attempts to modernize societies, liberalize women’s rights and blur the boundaries of the traditional Muslim family. Terrorism, according to Dicko, is a creation of the West and France to “recolonize Mali”. Dicko joined the open opposition (with criticism and participation in rallies) in 2017, opposing Keïta ‘s presidency and accusing him of worsening the security situation in the country and the economy. He had previously supported both the teachers’ strike and led a protest against legislative initiatives on family issues, and secured the resignation of former Prime Minister Boubéye Maiga, while maintaining popular support.

In an interview with Le Point, he talked a lot about his dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs in Mali and identified the main problem as the gap between the people and the elite, as well as a crisis of trust.

“Today, there is a divorce, a rift between the elite and the people, the ordinary citizen, who no longer believes in what they are told, because they have been told about justice, about the rule of law, about a state where there is freedom of expression, freedom of enterprise, where all citizens are equal before the law. But people realize that this justice, in reality, belongs to those who have the money, to those who are privileged. People have understood that the wealth that is in the country is badly distributed among the sons of the country, which is what creates this divide between the people and the elite”.

In the same interview, Diko criticises the Malian authorities for making good relations with the West a priority, forgetting about the people.

“I think their primary concern is not to reconcile with the people. Their concern is to be reconciled with the international partners, which is really the most important thing for them, and that is what creates this gap. The people should come first, and then these partners… My impression is that they are concerned about the vision that others have of us, that’s what worries them: what will France think of us? What is the European Union going to think of us? It is good to be concerned about this, because they are Mali’s privileged partners, but first of all, we must rely on ourselves…”

“He has achieved something huge: the Islamization of protest,” says Bakary Sambe, director of the Timbuktu Institute in Dakar.

“He criticizes the shortcomings of the traditional chieftaincy,” adds Bakary Sambe. What the West doesn’t perceive is that Salafism can embody an alternative form of modernity for the youth.” “Its success isn’t strictly religious, it can’t stay on the narrow agenda of classical Wahhabism,” shades the Islamologist Youssouf T. “It’s not just a religious success story. Sangaré, lecturer at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. When he entered the political field, he became the voice of all the discontented.”

Dialogue with jihadists and ethnic conflicts

In Mali, it is clear to everyone that the French army is not helping in any way to cope with the terrorist situation. In fact, on the contrary, it’s presence provokes even greater resistance among Islamist groups.

In parallel with the protests, an important event took place: the French military, according to the Ministry of Defence of the Fifth Republic, liquidated the leader of the local branch of the banned al-Qaeda group in the Islamic Maghreb, Abdelmalek Drukdel, and four other militants.

Le 3 juin, les forces armées françaises, avec le soutien de leurs partenaires, ont neutralisé l’émir Al-Qaida au Maghreb islamique (AQMI), Abdelmalek Droukdal et plusieurs de ses proches collaborateurs, lors d’une opération dans le nord du Mali.

— Florence Parly (@florence_parly) June 5, 2020

This is an important development, given that Drukdel is closely connected to memories of the Algerian civil war, which formed a key jihadi cell in the region.

And yet, it has not helped Keïta or his position too much. The problem is that the more the French intervene in the internal situation, the more radical the leaders of the Islamist cells in Mali become.

In this context, there is increasing news of an attempt by the authorities to engage in dialogue with groups. For example, Dicko has never made a secret of the need to engage in dialogue with jihadists in order to better understand each other and agree on peace. Dicko is a quite a unique person, he knows all the subtleties of Islamic branches, and who is respected by both radical Wahhabi and people, while being able to convey the point of view of the Muslim majority to the West (which is why he is often asked to give interviews).

“In the press, it’s true that I’m called a Wahhabi, a promoter of Wahhabism in the sub-region, but I think that’s an exaggeration. I am not a promoter of anything. People say things, make things worse, I think that today both Muslims and non-Muslims should get together to try to understand each other, it would often avoid unnecessary conflicts,” he told Le Point.

He is also a spiritual leader who leads informal conversations, but some of this dialogue takes place at the state level. In mid-February, President Keïta acknowledged for the first time that contact had been established with the two main leaders, Iyad Ag Ghaly and Amadou Koufa.

The response to the outstretched hand of the Malian president was a press release on March 8 from a jihadist group affiliated with Al-Qaeda, in which it stated its “readiness to enter into talks with the Malian government” but also set preconditions for any discussion: the completion of operations by Minusma (UN) and Barkhan (France).

Both are from al-Qaeda, but Ag Ghaly represents the Tuareg and Koufa represents the Fulani (Katiba group).

According to French political scientist Bernard Lugan, the main behind-the-scenes talks in the region are not related to the Islamic issue, but rather an attempt to resolve two key ethnic-political issues: the Fulani (hence the importance of dialogue with Koufa) and the Tuaregs (northern Mali, hence the importance of Ag Ghaly).

According to his version, even the death of Drukdel is connected with these backstage clashes – he was against the negotiations on these two lines.

Mali is fractured

All these events (the protests, liquidation of militants, behind-the-scenes negotiations with groups) are interconnected. Mali is a fragmented country divided into spheres of influence, torn apart by various conflicts. In addition to French colonialists and local jihadists, the Bambara, Fulani and Tuaregs, as well as the confronting centre of the Dogon Songay and other communities, play a key role. This means different languages, cultures and notions of governance: under normal circumstances, tribes are conditionally divided according to the principle of division of labour (some are hunters, some are plowmen, some are merchants, etc.). Plus, complex kinship relationships that guarantee the economic order.

But with the French intervention, instead of stabilising, the security situation is gradually deteriorating, as militants associated with al-Qaeda and Daesh strengthen their positions throughout the region, making large parts of the territory unmanageable and fomenting ethnic violence. The domination of strangers encourages local tribes to wage an open war over the division of resources.

The idea of trying to establish a dialogue with different groups instead of a dumb French attack on everyone indiscriminately does not therefore seem so meaningless. The people of Mali need reconciliation – perhaps based on the common Islamic factor (or even political Islam) with the preservation of local traditions and cults could be the solution for the country. But this requires, first and foremost, the dismantling of the institutions of Françafrique.

Thus, local centuries-old tribes with their own ways of life are left face to face with their own troubles – there is a balance between Western colonizers, jihadi gangs and the extortion of official authorities.

Not surprisingly, the people of the Sahel region are sometimes more willing to cooperate with specific gangs whose fee system is more understandable and “fair” than the corruption of pro-French elites.

The crash of Françafrique

The presence of brave French defenders is offset by the economic exploitation of the Sahel’s countries, which serve as resource bases and cheap labour, as well as years of financial control. All of this – foreign currency, foreign corporations, foreign supporters – prevents Africa from investing in its own infrastructure and creating a self-sufficient, independent Pole.

Failure Francafrique: why France is losing influence in Africa

Mali regularly holds anti-French demonstrations. For example, in January there was a large rally – the Malian anthem was played on Independence Square in the capital Bamako. One man was photographed with a sign that read “France go away”…

Salif Keita, a singer famous and popular among Malians, openly accused France of supporting terrorism in a video posted on Facebook. The singer appeals directly to the Malian President to stop “obeying this little Macron”. The French embassy in Mali condemned these remarks.

Anti-French sentiment has united the Groupe of patriotes of Mali (GPM).

Macron, of course, is starting to feel the results of the complete failure of Paris’ policies. He even threatened to deny African presidents military “help” if they do not reduce the anti-French tensions, something far easier said than done.

The situation for France in the region seems hopeless.

Possible scenarios for Mali

Given the growing authority of Dicko, it is possible that IBK will resign early. In this case, either Dicko himself will lead the country, or he will support a candidate who shares the same views and geopolitical guidelines.

Western middlemen are obviously concerned about the situation in which they might irrevocably lose their puppet ruler Keïta, afraid they might ultimately lose their business interests in the region. That is why, after a massive protest against Keïta, they have already gone into talks with Dicko, trying to negotiate possible loyalty and pressure him into compliance.

These figures came from the UN’s peacekeeping mission in Mali, MINUSMA; the AU; and the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), a 15-nation bloc that includes Mali.

What will happen as a result is an open question. If Dicko (or one of his allies) attempts to move away from the West and seeks rapprochement with Islamic states and “outcast” countries (Russia, China, etc.), Mali may have at least a chance to get out of the circle of eternal dependence of the colonialists and invest in its own infrastructure.

For Dicko (as has been predicted by experts) it will not be difficult to get closer to the Saudis. The country is already actively involved in finance projects in Mali: not long ago, the Malian Prime Minister expressed willingness to develop economic and trade relations with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in particular through the private sector. The head of the government urged the Saudi Fund for Development to speed up its support for additional funding for the construction of the Sevare-Gao road project, the construction of a military hospital and the rehabilitation of the Dakar-Bamako railway as soon as possible.

Another potential strong ally of Mali is Turkey, with which strong ties are already in place. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, President of Turkey, visited Mali in 2018 and expressed readiness to cooperate more closely. At the official opening of the countdown to the first edition of the International Industrial Fair (SIIM, April 19-21, 2018), on February 19, the Turkish ambassador to Mali said that trade between Mali and Turkey had reached $82 million in 2017, reports Anadolu.

At the same time, in recent years, Turkey has also been particularly active in the fight against terrorism with Mali, equipping its security forces.

“The Republic of Turkey will continue to support Mali, a sister country, in its quest for lasting peace and prosperity,” said Ambassador Hikmet Renan Şekeroğlu on the occasion.

At the same time, former chief military aide to Erdoğan, retired Gen. Adnan Tanrıverdi,who also owns private military contractor SADAT, said that Turkey should support Islamic groups against state terrorism in some critical regions of Africa such as the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali and Nigeria.

Russia has also emerged as a strong partner on security and counter-terrorism issues. In 2019, Mali’s Defence Minister General Ibrahim Dahiru Dembele signed a military cooperation agreement with his Russian counterpart Sergei Shoigu. For this Russia, of course, was accused of “intervention” in Mali.

But then how can one explain the voluntary petition of 8 million Malians appealing for Russia’s help? According to a survey published on December 11, 2019 on the website Maliweb, 89.4% of respondents in Bamako expressed the view that Russian aid could overcome the crisis, while about 80% opposed the presence of France.

And, of course, one of the key allies and partners of Mali is China, which has bypassed France both in terms of exports and imports in the trade turnover of countries.

Thus, although some fear Dicko’s coming to power as a “supporter of Wahhabism” and a radical, Mali’s course toward sovereignty and multipolarity is also a potential outcome of his leadership. This will depend on whether Mali has the strength to break with its colonial past, establish ties with alternative allies and use their finances for constructive purposes, such as developing its own infrastructure.

Leave a Reply